16 Authors Discuss Black Lives Matter, Anxiety, and More in May’s YA Open Mic

YA Open Mic is a monthly series in which YA authors share personal stories on topics of their choice. The aim of the series, above all, is to peel away the formality of bios and offer authors a platform to talk about something readers won’t necessarily find on their websites.

This month, 16 authors discuss everything from their parents to Black Lives Matter to anxiety. All have YA books that release this month. YA Open Mic runs on the first Thursday of each month. Check out previous posts here.

Kimberly Reid, author of Perfect Liars

On the news this morning, protestors were holding a sign: Kourts Keep Kovering for Kops.

I don’t know why everything was spelled with a K, but my first thought was KKK, even though there’s an extra K. Probably because I’m black, was raised in the South a long time ago, and once, as a young protestor myself, had hooded Klansmen throw rocks at me and my friends, black and white, as we marched together. So that sign made me feel one way.

But I’m also the daughter of a retired cop and the wife of a court administrator who I know have always worked for justice, so it made me feel another way, too. These opposing feelings run loose in my writing, especially in Perfect Liars, pulling me every which way.

Sometimes I watch the world, unsure which me to be. The one who has been stopped for driving while black? Or nine-year-old me who prayed my mom would be okay after she’d been badly beaten by a suspect?

I don’t have a choice, really. I will always fear blue lights in my rearview mirror. I will always remember the time at the mall when my mother, off-duty and unarmed, stopped two young men from throwing another down an escalator when no one else would, and I was so proud.

I’ve wrestled with this since I was a teen and friends jokingly called me narc, but more so recently, post–Trayvon Martin, post-Ferguson, post–Sandra Bland, post–too damn many. The reminders are in my Twitter feed, in private conversations, and in the steady paycheck my husband brings home which makes my not so steady writing career possible.

So I will always walk this line, mostly in my head and heart, silently. But because I get to do this thing I love, sometimes I can walk it in words.

Lily Anderson, author of The Only Thing Worse Than Me Is You

I used to hide under my dining room table.

Feel free to picture it: a 5’8″ plus sized girl of mixed ethnicity whose skin lightened and darkened with the season. Curly haired. Wearing eyeliner with Cleopatra wings on the edges. Underneath a table purchased from a yard sale.

The table was country cottage chic, if it helps.

At the first sign of trouble—a bill I couldn’t pay, a phone call I didn’t want to answer, in the middle of the night or first thing in the morning—I was off to the living room of my apartment, under that table, belly down on the carpet. Nothing could reach me in that confined space. I was safe to go fetal and hyperventilate. Sometimes until I fell asleep.

I’ve always been anxious. In fact, it was the main reason I left public school for independent study in the seventh grade. I started to flunk because I spent too much time in the nurse’s office with panic attacks and stress migraines. Anxiety kept me in jobs that I hated and relationships that were damaging because I was physically incapable of changing. Instead of confronting these problems, I would retreat to the smallest space available. When I was a teenager, this was usually my car or my closet. When I got my own apartment at 20, it was my dining room table.

I went on anti-anxiety medication when I was 25. Of course, it wasn’t a cure-all. Sometimes I get scared, wake up in the middle of the night, clam up when asked to make a quick decision.

But I’m out from under the table. In the world. Sharing my words with strangers.

It’s nice out here.

Erin L. Schneider, author of Summer of Sloane

Growing up, I had the typical relationship with my mom that most teens do—I pretty much ignored her on the best of days and disliked her a whole lot on the worst. We shared plenty of arguments and countless disagreements…but what I wouldn’t do now, to be able to go back and tell 17-year-old me to stop fighting, and instead, hug her fiercely.

In 2004 my mom was diagnosed with unexplained hepatocellular carcinoma—a fancy way of saying liver cancer. I was on a business trip in Miami when she called to tell me. And that the doctors had time-stamped her with a measly 4–6 months even with the most aggressive treatments and surgeries.

But my Mom had other plans. Bypassing all radical options offered, she instead took on an Eastern medicine approach. And because of these changes, it wasn’t six more months…it was six more years.

In the end, though, cancer challenged her body in ways it just wasn’t prepared to handle.

I spent my 34th birthday with my mom in hospice. I was by her side when she passed away three days later, on May 4, 2010, at 10:35 a.m.

Now, six years later—at a time that normally brings sadness and depression—it will instead be filled with a series of amazing events: May 1 is my 40th birthday. Two days later, my debut YA novel will be published—something I’ve dreamed about since I was a kid. And on Sunday, May 8, I’ll get to celebrate my first Mother’s Day.

I miss my mom every single day and I’m sad she isn’t here to celebrate such a huge year with me—we probably would’ve gone to Vegas for my birthday, she would’ve made the most ono food for my book launch party, and we would’ve shared the best Mother’s Day ever.

But somehow I know she’s keeping an eye on things from wherever she is…and there isn’t a doubt in my mind she had a hand in turning this otherwise sad time of year into one of the most memorable I’ll probably ever have.

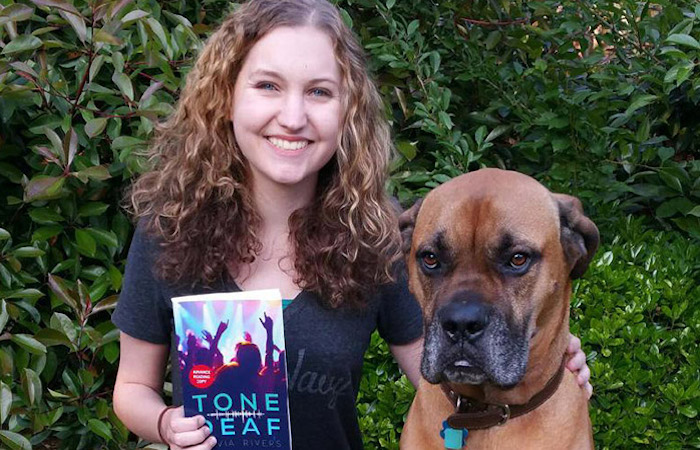

Olivia Rivers, author of Tone Deaf

A lot of authors have stories about how books saved their lives, but mine is a bit more literal than most. Back when I started high school, I got really sick and started having fainting episodes. I knew it was serious, but my doctors shrugged it off as symptoms of stress.

The thing is, I’m a calm person. I mean, if there was ever a nuclear apocalypse, I’d be the chick up on the rooftop munching on popcorn and watching the pretty explosions. So the “stress” diagnosis made zero sense. After months of no real answers, I was thirty pounds underweight, too ill to attend regular school, and confined to a wheelchair to avoid getting concussions when I fainted and fell.

That was when I stumbled across the book that possibly saved my life. It was a short memoir posted on the website Wattpad, written by a 14-year-old girl. Her story caught my attention because it was about experiencing the exact symptoms I had and getting an accurate diagnosis—Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, a rare nervous system disorder.

A new doctor tested me for the condition, and he confirmed I had it. My doctor also informed me I was at risk for having a heart attack or even a stroke. Luckily, I started treatments that kept this from happening.

I wish I could have thanked the girl who wrote that story, but she deleted her account and her story shortly after I found it. This is pretty common on Wattpad—people often come and go from the site. But her story had a profound effect on my life that I’ll always be grateful for. It’s something I try to remember when I work on my own books—sometimes it’s the smallest voices and their stories that leave the biggest impacts, even when we don’t quite know it.

Mia Siegert, author of Jerkbait

I was just shy of 14. I’d just moved to a new town and was in high school, the third youngest in the grade. Prior to moving, I had major issues with making friends because my passions were so broadly spread. I wanted to be popular, or at least have one friend. In the hallways, I heard students talk and say one thing again and again. So I tried it.

“That assignment was so gay.”

I didn’t know what it meant, or the negative connotation, but I was convinced it’d make me look smart and cool in my very conservative high school.

A girl, Brittany, turned to me, rightful rage on her face, and said, “How is it gay? What makes it gay? Why is it gay?”

I’ve never told that story to anyone. For 17 years, until this moment, I have kept it a secret. I never talked about my horrific epiphany, the on-the-spot realization that what I said was hurtful. What’s worse is that 13-year-old me didn’t apologize. 13-year-old me rambled excuses about it not being what I meant (which was true, as I didn’t know, yet that didn’t mean it was excusable).

This was years before I’d discover I identified somewhere on the spectrum. Sometimes I’m a girl. Sometimes I’m a guy. And I don’t feel it’s quite the definition of gender fluidity as there isn’t much variation. I just know. One day, I’ll wake up one way. One day, I’ll wake up another. Bigenderism, I call it, because it’s the closest thing that works for me.

Seventeen years later, my debut Jerkbait is about to release, chronicling the estranged twins Tristan and Robbie and the struggle of LGBTQ athletes. It’s a painful book, semi-autobiographical at parts, as it goes into gay teen suicide attempts and online predators and stress, stress, stress.

Seventeen years later, I still think about Brittany.

I wish I knew her last name so I could reach out on Facebook. I wonder what she would say if she knew who I was and what I identify as. I wonder how she would react if she knew what she said to 13-year-old me would reshape my entire life. Would I have questioned how I felt, sometimes a boy, sometimes a girl, and put a name to it if it wasn’t for her sharp wakeup call? Would I stop strangers who say homophobic or transphobic slurs? Would I have been so taken aback at anime conventions when people asked me, “Are you a boy or a girl?” “Why?” “Because I think you’re really hot and want to make sure it’s right.” Would I have felt the pain of going out in my guy clothes, losing my breath when I saw the most beautiful man in my life, and without me saying a word, him calling me “f****t”? Would I have understood the internal conflict of passing enough to be slurred at versus the pain of the word itself?

I’m not sure.

But I am sure of how grateful I am to Brittany, wherever she is. I wish I could say “thank you for making me the person I am today.”

And, more importantly, “I’m sorry.”

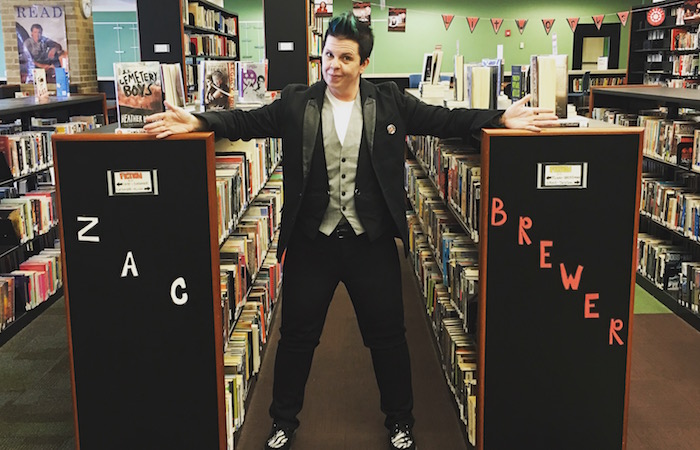

Zac Brewer, author of The Blood Between Us

I’ve been called a lot of things, for as long as I can remember. When I was six years old, my older brother nicknamed me “Bug Eyes,” because he hated that I stared at him so much. But the thing is, I wasn’t just staring at him. I was staring at everything. Observing the world around me as if it were my own little Sim world, long before The Sims even existed.

My mind was a stream of queries that would go on and on, stretching into a rainbow-colored eternity and out into the universe. The answers I received didn’t satisfy me. So I sought out my own.

I grew up in a world where the only good way to be was white, male, and certainly not one of “those” types—the types I would eventually come to know as “queer.”

It was a word people whispered throughout my childhood. It was the punchline of many jokes. It was the worst possible insult you could hurl at an enemy.

I didn’t do that. Instead, I wondered WHY.

Why was it so bad to be queer? And what exactly was it? The people around me all had very different ideas as to what it meant, but none of them seemed to be able to reach any sort of universal conclusion. What I gathered (in my young mind, with my limited resources) was that a queer person was a man who wore dresses and kissed other men who also wore dresses.

While I’ve found that’s not entirely untrue, there are millions of ways of being queer—and not one of them is anything to be ashamed of.

After years, I learned what it means to me to be queer: It means AWESOME.

Sarah J. Maas, author of A Court of Mist and Fury

When I was in 7th grade, I stopped reading.

I’d been an avid reader until that point in my life, adoring anything with magic or dragons or princesses (all thanks to my childhood obsession with fairytales), but I decided that year it wasn’t cool to read (and that the “dorky” things I was into—Star Wars, Indiana Jones, etc.—should never be mentioned again).

But I had a fantastic teacher that year. He noticed that I’d stopped reading—that I’d also pretty much become a willing airhead. He was concerned enough that he called in my parents and told them I needed to be reading. And if I hated what we read in class—which I 100% did, because the books didn’t have magic or dragons or princesses—then my parents should take me to the bookstore and let me pick some books I wanted to read. He ordered my parents not to hover, not to judge…their only job was to buy whatever books I selected. So my parents, lifelong readers themselves, listened.

They brought me to our local Barnes & Noble that very afternoon, and let me wander around—right into the fantasy section. An hour later, I walked out with Sabriel, by Garth Nix, and Robin McKinley’s The Hero and the Crown.

Those books changed my life in two ways.

The first, and perhaps biggest, was that those books (featuring heroines who got to have their own sweeping epics and romances) made me realize I didn’t have to hide parts of myself in order to fit some absurd society standard: I could be a girly-girl and still like Star Wars; I could love nail polish and still play sports.

The other thing those books made me realize was that I wanted to write fantasy. Especially stories with young women getting to save the world (later that year, Buffy Summers would also enter my life).

Within a few months, I was writing. And once I started, I couldn’t stop. Eighteen years and seven published novels later, I still can’t.

John Corey Whaley, author of Highly Illogical Behavior

Think about the smallest town you’ve ever been to. How small was it? The one I grew up in had about 7,000 people, maybe. That, friends, is small. My entire high school, grades 9–12, had fewer than 400 students total. There is no anonymity in a place that small. So, naturally, I was excited for college. Very excited. Out of my mind excited. I’d always hated my hometown. Everything about it, really. The old, dilapidated buildings on Main Street, the accidentally sarcastic yellow signs on all the light poles downtown, reading, “Springhill is Special,” and especially the townsfolk who I then believed couldn’t and never would understand someone like me. It just wasn’t the place for my eager-to-see-the-world, then-closeted 18-year-old self to thrive—and there was no swaying me to feel differently, ever.

When the time came to go off to college, my very courageous and rebellious nature managed to get me just one hour away from Springhill, to Louisiana Tech University in Ruston. One hour. But, this was a city, at least. Not a huge one, but it had coffee shops and a Wal-Mart that stayed open 24 hours a day and was just 30 minutes from Monroe, which had a movie theater. This was a big change for someone from Springhill. And it was supposed to be exactly what I’d always wanted. But I hated it.

I was lonely and I missed my family. I moved in with two high school pals and though we all got along, we weren’t all that interested in hanging out together. And my other, much closer friends very quickly got jobs and boyfriends and college social lives I couldn’t keep up with. On campus, I was invisible for the first time in my life. Anonymity, it turns out, is sort of terrifying when you’ve never had it. So, you know what I did? I drove back to Springhill—the place just too small to contain me—EVERY. SINGLE. WEEKEND. Because that was home. And home isn’t the things you hate about it, it’s the things you miss about it that you can’t find anywhere else. I had to learn to start dealing with my misplaced anger toward my hometown, and how that informed who I was, and that all eventually led to my first book. Whether it was fate or not, I needed where I was from to make me who I am—which is someone I’m still trying to figure out through fiction.

Ashley Herring Blake, author of Suffer Love

I started writing seriously when I became an orphan. That’s a strange word—orphan—and one most of us associate with kids and Oliver Twist. But orphanhood is ageless, a strange and untethering status. At 32, I found myself suddenly parentless, and the next couple of years were a slow process of relearning how to breathe, how to move through the world. At some point, I realized it wasn’t a matter of relearning, it was simply a matter of accepting that I would never be the same person I was when my mother was alive. And that was okay.

I was okay.

As a kid, I was always reading. Judy Blume, The Babysitter’s Club, Anne of Green Gables, Jane Austen and the Brontës and Woolf. I loved words, the worlds contained inside them. I wrote stories when I was in elementary school, but threw myself into poems as a teen and young adult. My sophomore year of high school, I won the county writing fair with a poem called “The Kaleidoscope of Song,” and it was just as awful and cloying as it sounds. In my twenties, I fiddled with short stories and more poems, but it wasn’t until my mother died that I realized that I really did want to be a writer. That I’d wanted to be a writer all along. I’d always had stories hiding in me and it took a shock, a rebirth, to draw them to the surface. In many ways, her death roused me awake and into motion. Into life.

Losing someone sucks. There’s no way around that. But I think it’s a beautiful testament to my mother’s life that her legacy birthed in me an awareness of my worth, of the blood in my veins, and all the stories that only I could tell.

M.G. Reyes, author of Incriminated

I’d just turned 12 when my mother told me her second marriage was over.

Husband #1 was a brilliant, difficult man. She managed to leave him with her head held high. But Husband #2 was True Love. That’s why it hurt so badly when he cheated on her.

A 12-year-old has little concept of how psychological trauma can ravage a person. “This will all blow over in a few weeks,” I thought.

It didn’t.

Many tearful nights followed. My mother needed almost constant comfort. I would whisper prayers of thanks when any well-wisher came to visit. The rest of the time she only had a 12-year-old who could barely comprehend what it meant to be abandoned, and two younger kids who didn’t understand at all.

Perhaps the worst moment was the night I found my mother on the phone to the Samaritans—a suicide support service. Everything that had happened since he’d left us went into sharp relief. I thought we were adapting, but that was just me and my siblings. My mother was fighting for her life.

It took me years to understand that if someone has chosen to ask for help, it’s a good sign. It means they probably want to live a bit more than they want to die. I shouldn’t have been paralyzed with fear, I should have been glad that she was reaching out to an experienced helper.

Divorce and bereavement can force a child into the position of young caregiver, providing support to a depressed parent, babysitting younger sibs, shopping or cooking for your family. It’s more common than you might think!

Like most caregiving youth, I just got on with it. It may be a good way to practice for when you have your own family, but be sure to get all the help you can. You deserve it!

American Society of Caregiving Youth: http://aacy.org/

Jenn Marie Thorne, author The Inside of Out

When I was 14, I decided the real me was a fifth-century druid priestess.

A couple of things had led me to this sorry state. For one thing, I’d read The Mists of Avalon over the summer and I was in raptures over it. And, before that, I was bullied. I was The School Nerd from third grade to eighth, long before “nerd” had any positive connotation. I’d weathered years of desperate loneliness and daily, petty humiliations, finding solace in the book worlds I escaped to the moment school let out.

Things were better by high school—I’d switched schools to one that got me, I had friends, I felt marginally less uncomfortable in my glacially blooming body—but I couldn’t shake the feeling that I’d been born into the wrong dimension. The real world wasn’t made for me. It was too flat, too plain, too casually cruel.

My house bordered on forest. Afternoons and weekends, I wandered the footpaths, dangled my feet in the cold creek, clambered over rocks to the teeny island midstream, and waited for magic to happen. It had to. Otherwise, why had I gone through the rest of it? I had to be special, dammit. I had to develop precognition, or commune with fairies, or move objects with my mind, or maybe become a movie star or a New York Times bestselling author or—

Or I could stop. Enjoy the creek. The light flickering through the oak branches. I could remember that if I’d been born in the fifth century I probably would have died from a childhood illness, and I’d have crooked teeth, and I’d be blind because there was no such thing as contact lenses.

This is my twenty-first-century life, for better or worse. And now I make my own magic.

Laura Tims, author of Please Don’t Tell

From middle to high school, I went from 0 mph to 100 mph.

In middle school, I was the girl who never talked, who was in such a perpetual state of frozen terror that she sweat through all her clothes until she got prescription-strength deodorant. In high school, I was the girl who dyed her hair five different colors in a month, pierced her own nose with a sewing needle, and made it her business to be the loudest, most obnoxious person in her group.

In reality, my social anxiety was still so severe I needed my boyfriend to come with me to every party. I was lucky he came to the same college as me. But even in hangouts with close friends, there were times I’d break into a cold sweat and need to go upstairs alone.

I was afraid of people because I assumed they’d think I was weird or wrong or unfit for social interaction, because I assumed I was weird or wrong or unfit for social interaction. At least with my boyfriend there, I figured, people would be nice to me because he was likable and I was his girlfriend.

But after six years, we broke up, and a miracle happened—people were still nice to me. I learned I could make friends without him. In fact, it was easy. When I moved across the country to a city where I knew no one, I found a good friend group pretty fast!

I thought social anxiety was something I’d have to deal with forever, but it wasn’t. I thought I was weird or wrong, but I’m not. Turns out you grow out of even the stuff you thought was permanent!

Mia Garcia, author of Even if the Sky Falls

I try really hard not to be a bummer. In fact I think it’s a family trait, we can’t be serious for more than 10 minutes max. I don’t open up a lot. I’d like to say I’m working on that but I don’t think I am. I have a problem asking for help. I am working on this. Maybe. I love horror movies even though they keep me up at night.

I’ve stopped and started this thing 800 times and still have no idea what to write. I am kind of a jerk to myself. I have a hard time writing unprompted short essays. I get confused by people who “aren’t really into sweets,” because who are you and how are we friends? I think I’m better at bowling than I actually am. I am proud of the number of times I’ve been to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter. I am an Aquarius. I am the youngest of four. I’ve been “getting back” into yoga for the last year. I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. I didn’t know my grandmother spoke English until I was 15. I can’t sleep even though it’s 2 a.m. I should be sleeping. I will regret not sleeping tomorrow. I’ve lived in Scotland and often dream of living in a small cottage in the highlands with some sheep. I’m not sure who will take care of the sheep in that scenario because I know nothing about sheep. I miss my dog. I feel lost and confused a lot. I’m trying to take better care of myself. I hope I actually can. I worry about being liked and have trouble saying what I mean. If I had the power to fly I wouldn’t get very high because I’m afraid of heights. I don’t think I’ll ever win the Hamilton lottery. I had no idea how to start this, and now I have no idea how to end…

Stacey Lee, author of Outrun the Moon

Failure is a better teacher than success. Recently, my older sister was going through some of her old boxes and discovered she had won the blue ribbon in a swimming competition when she was seven. She didn’t remember she had won it, but she was very excited to show her kids, who had never thought of their mother as an “athlete.”

By contrast, I remembered this same swimming competition as if it were yesterday. While my sister was winning the breaststroke, I was in another part of the pool, losing the backstroke. I remembered how, mid-pool, I got off track and started going diagonally, and when I looked up, everyone was already out of the pool receiving their awards.

I didn’t just come in last place, I came in NO place, as everyone had forgotten I was still in the pool. I went home and cried so hard, my mother, who was more of a “keep a stiff upper lip” kind of person, let me cry on her lap until I fell asleep.

I’ve returned to that memory many times over the years, mostly to remind myself that even in the depths of my humiliation, I still got out of the pool. Winning is wonderful. But losing can teach you a lot, too. It can teach you how to keep going, and that might be the most valuable lesson of all.

Evelyn Skye, author of The Crown’s Game

It would be nice to pretend that The Crown’s Game was the first book I wrote. That would be a great story: author’s first manuscript lands her a rock star agent and a fantastic book deal.

But that’s exactly what it would be: pretend. The truth is, I wrote eight other manuscripts before The Crown’s Game, and I had another agent, who tried to sell many of those manuscripts for three years, to no avail.

And yet, I’m glad. Because The Crown’s Game was the story that was supposed to be my debut. This book is courage and perseverance and faith all wrapped into one. It is the courage to leave my previous agent, even though he was lovely. It was the perseverance to keep on writing, even though eight other novels hadn’t sold. It was the faith that I was meant to be a writer, that if I kept working hard enough and long enough, I’d reach my destiny.

The book is also very me. It’s a love story—the kind of fierce love between lovers, yes, but also between friends and within families—and what happens when that love twists and bends and breaks. It’s a story about Imperial Russia, a world I spent my college years studying and loving. And it’s a story about magic: the power of magic, the possibility of magic, the very existence of magic.

I believe in magic. I believe in the magic of patience in a world where it seems everyone is moving faster than you are. I believe in the magic of perseverance when the tide seems determined to push against you. And I believe, more than anything, in the magic of each and every one of us, and the stories only we can tell.

If you listen carefully, you’ll hear the magic, too, calling. It whispers, Be patient. You can do this. Keep writing the words of your soul, and one day, this will be your story, too.

Harriet Reuter Hapgood, author of The Square Root of Summer

Let me tell about the wedding I always dreamed about as a little girl…Haha! Nope. For some reason this was the hot topic at nursery school—it was the 1980s, taffeta was big—and when I said “I NEVER want to get married,” it was clear I was the weirdo, mister.

Even at five I recognised this as BS. I’d been a Ms. not a Miss since I could talk, and my mum had taught us to hang up the phone if someone called asking for “Mrs. Hapgood.” (I have both my parents’ names.)

“But you have to,” a girl once said to me, which caught me out. So I came up with the because-I-have-to Dream Wedding. On the beach, because I liked to swim. Bride and groom would wear the same outfit, because equality: goggles, bare feet, jeans, bare chests. (I was not prepared for boobs.)

When someone says you have to do something, you can still try to do it on your terms.

The key aspect of this wedding was being grownup—doing exactly what I wanted. No one would make me wear a T-shirt, or greasy suntan lotion, and I could run into the sea with my jeans on (yes!) and swim with my head under water.

I still think this is a pretty good wedding, and I still don’t want to get married. And now I’m a grownup for real, I do exactly what I want, including not paying any attention when someone says I have to do something.