The Voice: Tracey Thorn’s Pop Journey

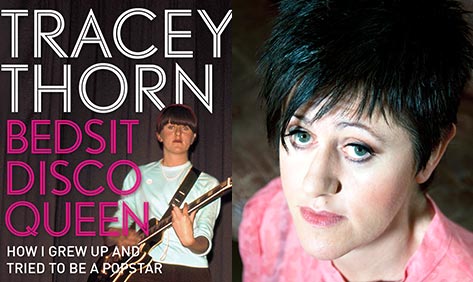

In August 1979, sixteen-year-old Tracey Thorn bought her first electric guitar from an ad in the back pages of Melody Maker. It was the height of the British punk era, and she and her suburban friends were already getting “dolled up” in skinny jeans, borrowed policeman shirts, and cheap stilettos and going out to gigs to see the likes of Ian Dury, Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Jam, the Buzzcocks, and X-Ray Specs. But she had neglected to buy an amp or a lead and had to play her electric guitar unplugged. Out that youthful misunderstanding emerged a musical hallmark, the “quietness thing” as she calls it in her memoir, Bedsit Disco Queen, “born of necessity, ignorance and embarrassment. Only later will it become a kind of manifesto.”

In August 1979, sixteen-year-old Tracey Thorn bought her first electric guitar from an ad in the back pages of Melody Maker. It was the height of the British punk era, and she and her suburban friends were already getting “dolled up” in skinny jeans, borrowed policeman shirts, and cheap stilettos and going out to gigs to see the likes of Ian Dury, Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Jam, the Buzzcocks, and X-Ray Specs. But she had neglected to buy an amp or a lead and had to play her electric guitar unplugged. Out that youthful misunderstanding emerged a musical hallmark, the “quietness thing” as she calls it in her memoir, Bedsit Disco Queen, “born of necessity, ignorance and embarrassment. Only later will it become a kind of manifesto.”

Later that year, she became the rhythm guitarist and “token girl” in a high school band called the Stern Bops. When they asked her if she could sing, she nearly refused. “Playing rhythm guitar in a band was one thing,” she writes, “it was easy to hide behind your guitar and behind what the other guitarist was playing, but being the singer put you fair and square in the middle of the stage.” She finally agreed to sing — a cover of David Bowie’s “Rebel, Rebel” — but only if they allowed her to do so while hidden inside a wardrobe. Though she would go on to have one of the most distinctive and immediately recognizable voices in British pop music, Thorn ceded the lead singer position to a boy in the band.

Thorn, a budding feminist, soon realized that the only way to get out from under the boys would be to form an all-girl band. And by age seventeen, she and two girlfriends put together a three-piece called the Marine Girls (they had no drummer, because no girls they knew played drums). She borrowed a four-track recorder she didn’t know how to use, and the Marine Girls became the first teen band in their town to record an EP, sold at the local record store and to anyone who sent a postcard to Thorn’s parents’ home address — listed in an ad Thorn placed in the back of NME. Interviews with Dutch fanzines, reviews in the indie music press, a contract with Cherry Red Records, and a second LP, this time largely recorded and produced in a garden shed (“Not so much garage rock as shed rock!” Thorn writes gleefully) followed. “We were as industrious and self-motivated as any conservative parents could ever have wished for,” writes Thorn, “and it simply never occurred to us that there was any reason not to do these things, or anything that could stop us.”

But pop stardom seemed risky career path, and Thorn, always a good student, enrolled in college in 1981. Five hours into her first day of college, she was paged at the student union bar: “If Tracey from Marine Girls is in the building, will she please come to reception?”

The guy waiting for her was her Cherry Red label mate Ben Watt. After a brief introduction, he asked, “Have you got your guitar with you?”

And thus began an artistic and personal collaboration that would result in eleven studio albums, four EPs, thirty-one singles, one marriage, and three children. They called their band Everything But the Girl.

Thorn thought it was cooler to be in an all-girl band than a two-piece with the person who would soon become her boyfriend, so at first she stuck it out in both bands, with Marine Girls and Everything But the Girl and Ben Watt’s solo stuff trading off weeks in the NME and Melody Maker. She still has a clipping from Melody Maker that shows Everything But the Girl’s single “Night and Day” at number one and Marine Girls’ “On My Mind” at number nine.

But Thorn had long felt stymied by passing off songs she had written to be sung by the Marine Girls’ official lead singer, and was becoming frustrated with the band’s unpolished, punk aesthetic. (“From a feminist perspective, I was beginning to feel that it was pandering to an audience’s patronizing expectations of female musicians to remain at this shambolic level.”) Marine Girls finally broke up after a meltdown at a gig in 1983. Over the next two decades, Thorn would find out the band had influenced LCD Soundsystem, Calvin Johnston of Beat Happening, and Courtney Love, and had been one of Kurt Cobain’s favorite bands.

Watt knew more about jazz; Thorn more about punk and pop; together their sound was both more sophisticated and musically complex than the deliberately lo-fi punk of the time, but with more edge and menace than their relatively quiet sound would suggest. By the time they finished their final university exams in 1984, they had played a gig with Paul Weller of the Jam, and had their first single in the charts. Everything But the Girl became one of the signature bands of its time, and Thorn and Watt toured and recorded albums together for the next two decades, scoring their biggest chart hit — “Missing” — in 1995, more than a decade into their career. Their last record together was recorded in 2000. Since then, they have had three children. Watt has also worked as a DJ and written a memoir of his own, called Patient. Thorn has recorded three solo albums of her own since 2007. I spoke with her via e-mail from their home in London. — Amy Benfer

The Barnes & Noble Review: One of the lessons from your career is how playing quiet music can be a radical act in rock halls accustomed to noise, and how easy it is to be misunderstood. You write about feeling that you were a little too early or too late for many major music trends. And yet quiet-as-the-new-loud seemed to be the cutting edge of the non-grunge mid-’90s (trip hop, lounge, shoegaze, slowcore, the fabulously named “sleazy listening,” which I had never heard before),. you were obviously welcomed into the fold — recording with Massive Attack, scoring your biggest hit ever with the remix of “Missing.” Do you see ways in which your own work may have directly or indirectly influenced these later artists and movements?

Tracey Thorn: Oh yes, I’ve definitely realized now that the stuff we did earlier on in our career — even though sometimes it felt like it was misunderstood at the time — was often quite well understood by other people who were then inspired later to make music. So, for instance, Massive asked me to work with them because they heard and loved “A Distant Shore.” Many remixers wanted to get their hands on “Missing” because they’d loved earlier tracks like “Driving” and could see the through line from one period to another.

Tracey Thorn: Oh yes, I’ve definitely realized now that the stuff we did earlier on in our career — even though sometimes it felt like it was misunderstood at the time — was often quite well understood by other people who were then inspired later to make music. So, for instance, Massive asked me to work with them because they heard and loved “A Distant Shore.” Many remixers wanted to get their hands on “Missing” because they’d loved earlier tracks like “Driving” and could see the through line from one period to another.

And I’m aware that we have influenced a new generation of bands out there now, most especially the xx, who make it very plain that they were completely inspired by us. Romy cites hearing “Missing” on the radio, and it being the first song she remembers singing along to.

So in the end, perhaps it doesn’t matter, being a bit out of step at the time. Maybe that in itself stops you blending in too easily and getting lost.

BNR: Your voice is one of the first things critics mention about your work, and yet you hesitated to become a singer — you felt being a guitarist was a less conventional choice for a girl, and you shied away from the attention given to the Female Vocalist. You describe the Voice as something that you almost feel doesn’t belong to you, like beauty. How did you become comfortable with using your voice? Was it something as simple as discovering your voice as a songwriter first and feeling you were the only one who could sing your songs? Discovering the expressiveness of your singing voice itself? How did you reconcile yourself to the inevitable spotlight that comes with being the singer?

TT: I’m actually writing a whole book about this now — about singers and singing. I felt I only touched on it in this book, as I was hurrying through the story, and I realized there was much more to say.

I think I discovered my voice fairly gradually — not at all in my first band, then a bit with the Marine Girls, and then properly when I recorded “A Distant Shore.” From that point on I felt a very strong desire to sing my own songs, and that was where the Marine Girls began to fall apart.

But at that stage the spotlight was very small, and it didn’t truly occur to me that I was pushing myself to the front. The problems that came with that only became apparent later on, when I realized I had put myself right into the center stage position, and then had to get used to being there. I’m not sure I ever did fully reconcile myself to that.

BNR: First you were the token girl in an all-boy band. Then you were a member of the Marine Girls, an all-girl three-piece band.Then you were a member of Everything But the Girl, a two-piece band with your college boyfriend, who became your husband and the longest musical collaborator of your life. Finally, you went back to working as a solo artist. Your first solo album, written alone and recorded in private, was the kind of low-tech bedroom record you’d started out making as a teenager. Having done all that, what have you learned about what works best for you as an artist in actual, as opposed to ideal, practice? Or are there different kinds of songs and/or songwriting that are better suited to a certain kind of collaborative or creative process?

TT: Well I learned that collaboration is valuable — in that you get other people’s ideas added to your own — but always difficult — in that you have to compromise with them. In the Marine Girls I think we communicated quite badly, partly because we were so young, and then we were separated geographically, but tried to carry on. Too much went unsaid, and that’s not good for collaboration.

With Ben, the collaboration worked very well most of the time, but I think once we stopped working together and started to do separate things, it seemed harder to think of going back to working together again. Maybe because we did it for such a long time, and it does add an element of strain to a personal relationship — that’s one more set of things to agree on!

Now we have kids, I’d find it very hard to re-combine every element of our life again, so that we were partners, parents and musical collaborators. There has to be a degree of separation.

BNR: I’m fascinated by how few of the bands loosely — and often sloppily — referred to as “college rock” in the United States actually went to college. You attended and completed college; after your fifth or so record you went back for a master’s degree; throughout you even considered getting a Ph.D. Do you see ways in which your academic and/or intellectual life has influenced the way you write a song or tell a story?

TT: First off, I’ve always thought the “college rock” label refers more to the listeners than the bands themselves, so it doesn’t really matter if the musicians went to college or not.

As for my own education, I’m never sure whether it has helped or not. It helps with the stuff around the music, the doing of interviews etc — the ability to be articulate about your work and explain to people what you’re trying to do and why. It helps me make sense of the way things go. But I don’t think it helps you to write songs, they come from somewhere else.

The term “college band” of course isn’t used at all in the UK, so it’s not a label we’ve ever had to think about much.

And here, the thing that makes people think you are “posh” or not, is having gone to private school. There is some discussion about that at the moment as there are quite a few successful pop stars who have this background and people are wondering why.

BNR: You point out that being a pop star can be “infantilizing” (you have everything done for you but you can’t make decisions; any request can be read as a complaint). At another point you write about how being on the road really is like being in “Spinal Tap.” And yet, you graduated straight into the world of touring right after college, having already spent your teen years making tapes, playing gigs and being interviewed for NME. How have you seen this damage the lives of others? How did you try to protect yourself (if you did!) from being damaged yourself, having spent your entire adult life as a pop star?

TT: I think that, without even consciously deciding to, I protected myself by always feeling that the “popstar” bits of life were only part of the story — being on tour only happened part of the time, then you’d be back to what I considered normality. So there were periods of living this slightly infantilizing life, but then periods when you reverted to being an adult, looking after yourself, and during those times I did live a very normal life, thus avoiding damage.

BNR: You are not the least bit shy in using the word feminism throughout the book and identifying yourself as a feminist. It reminds me of this recent piece in Jezebel titled “The Many Misguided Reasons Famous Ladies Say I’m Not a Feminist” in which many actresses and pop stars — from Lady Gaga to Beyoncé to Melissa freaking Leo — give various reasons why they do not describe themselves as feminists. What do you think makes you cool with it and others less so?

TT: I just read all those quotes and I find them completely infuriating and depressing. It’s very sad to see the wide range of women who have been browbeaten into thinking it’s a negative word, all about complaining and hating men. I wonder if several of those quotes are from a few years ago, because I think there was a period when the word sent very out of vogue with younger women, so maybe that’s one explanation.

But still, to me it’s a bit unforgivable to be so easily manipulated, so eager to buy into the backlash against feminism, and so apologetic about the fact that you might be making demands of society. That’s what makes me angriest — the tone of apology, even from otherwise sensible women.

On the positive side, certainly in the UK the word and thus the concept has had a renewed currency, partly thanks to a lot of younger outspoken women like Caitlin Moran, Laurie Penny, lots of feminist blogs and websites. There is currently much feminist discussion going on about popular culture — Robin Thicke, Miley Cyrus, Lily Allen, etc. — which is good, although as an older woman I do obviously sometimes find that the conversation is happening at a very basic level, and I feel I can’t really join in as I want to move things further along, and that would be unfair to younger women who are only just starting to talk.

But I don’t know why I’ve always been happy with it, and these other women aren’t. There’s no connection between any of them, in terms of commercial/indie that would explain it, they’re from all walks.

I’m just happy that younger women are coming round to it again. My 15-year-old daughter has just joined the Feminist Club at school, which I’m proud of.

And I’ll just carry on — I always feel never apologise about being a feminist, never let them make you feel you have to own up to it with the caveat of not being too aggressive, or too strident, or not hating men.

BNR: You talk about the chronic restlessness of looking for the elusive role models in music: For example, you mention feeling more comfortable with the ’70s-era androgyny of Patti Smith, who claimed to cop some of her style from Keith Richards (as you say you did from Morrissey) than say, the ’80s-era do-me feminism of Madonna. But you also find inspiration in torch singers and the ladies of old Hollywood, who seem nearly opposite — rather than male swagger, they seem to epitomize female vulnerability in a game that’s rigged by the men. I find it especially fascinating that by the time the ’90s roll around, you discover that your first band, the Marine Girls, has jumped the pond and is credited with inspiring not only the explicitly feminist bands of the era (Bikini Kill, Hole, etc) but also the guys — including Calvin Johnston, James Murphy and Kurt Cobain (who included Marine Girls in his top bands and also, like you, admired Frances Farmer). Is it a hopeful thing (or a new thing) when dudes openly acknowledge their female musical influences? Or should we not mention it at all and just take it as cavalierly as we do Patti and Keith; you and Morrissey?

TT: I don’t think I found the Hollywood ladies were role models, it was more that their stories were so awful, such archetypal tales of setting women up only to knock them down, that they were rich for inspiration.

As for the 90’s dudes, I think they were very consciously trying to escape masculine role model clichés, and were choosing women in order to help them come up with different templates, and identify themselves with something other, something very non-male.

Personally I like that, I think it is probably good for both men and women to make moves towards androgyny — ultimately what you’re looking for in that is a common humanity. I don’t like those earlier quotes about “I’m not a feminist, I’m a humanist” — that just seems wishy washy nonsense to me, and a cop out. But I do like the idea of saying, “Look, society oppresses women, and has come up with these massively gendered stereotypes for us to live up to. Let’s try and dismantle them a bit.”

BNR: You write at one point that you believe in a classic second wave feminist mantra that “the personal is political” and that telling stories about women’s domestic lives can itself be a political act. Many of your lyrics (“Long White Dress,” “Trouble and Strife,” many others) express ambivalence or outright horror at the idea of living the life of a wife according to conventional definitions. Also, many of your songs written long before you became a mother expressed the desire for children or were written directly from a mother’s perspective. Your work has critiqued the potential limitations of love and domesticity on a woman’s life, while you seem to have found a way to enjoy these things in your own life. How have you created a domestic and creative life for yourself that escapes those limitations? And do you see a difference between the songs you wrote on motherhood before and after becoming a mother?

TT: Well I’ve never denied the fact that the lifestyle I’ve been able to choose is a luxury, a set of choices only available to me because of how successful I’ve been.

I gave up music for a few years in order to be at home with the kids, but I’m sure I only wanted to do that because I’d already had such a fulfilling creative life throughout my 20’s and early 30’s. In ambition terms I’d achieved more than I’d ever really wanted to, so there was nothing I was turning my back on.

So I had the time at home with the kids, which was brilliant — liberating for me in that I escaped some of the stuff about being a pop star that I found boring.

But someone said rather snidely to me on Twitter the other day that I had sold out my feminist younger self because I was now a housewife, and I just thought, that is bullshit really.

The point I go back to is, I’m in the luxurious position of being a creative artist who doesn’t have to work all the time, or scrabble around doing work I don’t want to, just for the money.

But since I had the three kids, I’ve also written a book, and recorded three albums, which isn’t really the behaviour of the oppressed housewife.

I’m not at home cleaning the house and ironing Ben’s shirts while he is out at work — we’re both at home, writing usually, working on new projects, sometimes out doing promotion for something or other, but quite often here when the kids get in, eating an evening meal together. It’s a fortunate blend of work and domestic life, and I’m very grateful for it.

BNR: I don’t entirely know what to make of it, but I sort of love that throughout you talk about the search for your “girl gang” and the two times you seem to find it are as a schoolgirl just getting into punk rock (where you freely admit the girls you hang with maybe a bit rougher than those you might otherwise choose) and as a new mother (where you admit the cult of the stay-at-home mothers maybe more traditional than your usual crowd). What are your thoughts on that?

TT: I’ve searched for my girl gang, but I think at heart I have to admit that I’m not really a gang kind of person.

Ben had to describe me for a profile in the paper recently and he said, “the thing about Tracey is, she’s half wallflower, half freedom fighter.”

I think that’s pretty fair — I was a bit wallflowery for the bitchiness of the teenage gang, but too much of a freedom fighter to really fit with some of the at-home mothers.

So in the end I find my friends here and there, people who are a bit of a mixture like me.

Since joining Twitter I think I’ve actually found my third “girl gang” which is all the very vocal women, many of them journalists, who I chat to much of the time, and many of whom I’ve now met up with in real life and become friends with. They’re people I didn’t often meet while making music all the time — or if I did, sometimes they were on “the other side,” in that there can be a bit of a divide between musos and journalists. But now, I’m much more at ease with all that, and I realize that these outspoken, literate women are perhaps the kind of friends I was always looking for.

BNR: As a songwriter, you seem to write both autobiographical lyrics and narratives about fictional or somewhat fictional characters. For this book, you seem to have had to look at yourself as a character: You consulted your own diaries (sometimes to hilarious effect), critiqued your own songs written as a younger woman (I love how sometimes you sound like you are essentially reviewing your own early music), and looked back at the culture in which you grew up. How is this kind of writing different from that you have done before? What have you learned about yourself as a writer and as an artist?

TT: It was different from anything I’d done before. The hardest thing was deciding what tone to strike — how seriously to take myself, how hard to be on myself, how much to judge, how much to forgive.

I ended up opting for honesty as much as possible — owning up to the mistakes, admitting that things often look funny with the benefit of hindsight — but trying to present the things I did in all the sincerity with which they were intended at the time I did them.

I realized though that I simply wouldn’t be able to adopt the slightly pompous tone you often get in autobiographies, where “the work” is all taken extremely seriously, and there is a sort of po-faced reverence about “the artist.” I think those judgements are best left to others, you can’t talk about yourself in those terms. You just have to describe what you did — admit to the bits that don’t work — it takes courage to laugh at yourself, more probably than to take yourself ultra-seriously. But at the end of the day, this is just pop music we’re talking about, it’s better talked about with a lightness of tone.