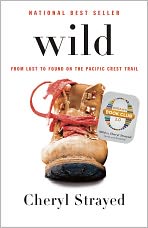

A Conversation with Cheryl Strayed, Author of Wild (Discover, Summer 2012)

The Discover selection committee had nothing but accolades for Cheryl Strayed’s captivating, audacious memoir of her solo hike on the 1,100-mile-long Pacific Crest Trail — and so Wild is one of the titles we’re featuring in our upcoming Summer 2012 season.

Cheryl answered some questions about her book — and the reading she did on her journey — for Discover Great New Writers, and we’re sharing it here.

Wild charts your 1100 mile solo hike on the Pacific Crest Trail in 1995 when you were twenty-six. What made you decide to write about this part of your life now?

I always knew my hike on the PCT was important to me as person, but I only recently thought the power of that experience might translate onto the page. I teach memoir on occasion and the question I’m always pushing my students to answer in their work is not what happened, but what it means. I think that’s why it took me more than a decade to begin writing about my hike. I had to figure out what it meant. I couldn’t do that until I’d lived a while beyond it; until I’d moved solidly out of the era of my life that I write about in Wild. At its core Wild is a story about a woman figuring out how she’s going to live in the world given the facts of her life — some which are painful. I couldn’t tell the story about how that woman figured it out until she really had.

How did you get the idea to hike the PCT?

I didn’t know my journey would hold any answers, but I was out of solutions. I wasn’t getting them in any of the other places I was looking. In some ways, my decision to hike the PCT was nothing more than running away to a place where no one could reach me, where I’d be far away from the sources of my greatest sorrows and consequences of my mistakes. But in other ways, I was running toward something too, and I knew it instinctually even then. I’d grown up in the woods of northern Minnesota, a land that’s beloved to me. My faith in the silence and wonder of the wild places feels as if it’s written in my blood. So that’s where I went. The PCT was a foreign land to me then, but it was also something like home.

You confront a lot of emotions on the trail but one of the most palpable is the fear of being alone in the wild. How did you do it?

I opted to make fear my companion rather than my ruler. It could walk alongside me, but it wasn’t going to be my guide. It was a conscious decision I made about my life. I’m not braver than most people. I was able to hike all that way alone because I decided to be brave. When I felt afraid, I told myself I was not afraid and I simply continued on. A lot of things happen to us in our lives that we can’t control, but we do get to control how we respond to them. From the moment I decided to hike the PCT I knew that fear had the power to keep me from doing what I wanted to do, but only if I allowed it to. I chose not to.

You write very honestly about how woefully unprepared you were for the trip. Looking back now, are you ever surprised that you made it?

You write very honestly about how woefully unprepared you were for the trip. Looking back now, are you ever surprised that you made it?

Yes and no. I must say, there’s a part of me that’s amazed I stuck it out. I mean, it’s not as if I went out there running on the steam of a years-long dream of hiking the PCT. I was miserable so much of the time and in at least some pain pretty much always. But I tend to be stubborn. If I say I’m going to do something I’m usually going to do it. And there was enough beauty and wonder in each day that I always wanted to see what would reveal itself in the next. I also learned a whole lot. I stepped onto that trail ill-prepared and naïve. I stepped off of it a seasoned backpacker. That’s what I love most about backpacking. You can talk about it all you want, but it’s the trail that teaches you how to do it. Once I was in, I wasn’t going to stop.

How did the other people you met at various points on the trail help you in your journey?

I often went days without encountering another human being. The solitude was tremendous — far more than I expected — and so when I met someone it was a fairly momentous occasion. I had an immediate sense of kinship with others who were hiking long distances on the PCT, like we were in something together, even if we’d only just met. Generosity was a given, as was kindness, respect, and a willingness to share one’s supply of chocolate. Many times it was those people I met on the trail who kept me going. They cheered me up and made me laugh. They agonized or strategized with me. Most importantly, their presence convinced me that if they could do this, so could I. I also met people who weren’t hiking the PCT, who instead were impressed, appalled or confused by what I was doing, and they were equally important. They were like a collective grounding wire for me, keeping me rooted in the world that was outside the PCT. After all these years, I’m still overwhelmed by the generosity of the many strangers who passed briefly through my life that summer. So many people were so good to me. It’s something one never forgets.

Let’s talk about boots. Perhaps your most important relationship forged on the PCT was the one with your boots. Would it be safe to describe this as a love/hate relationship?

My boots were the bane of my existence! They felt almost alive in their cruelty, as if they were intentionally causing me pain. When I lost one over the side of a mountain I was horrified, but I was also filled with a giddy relief. It was as if I’d been on a long, torturous road trip with the most miserable person on the planet and I’d finally and at last insisted he pull over so I could get out. Which is great, but then you’re standing there by the side of the road. What next? In Wild, what was next is precisely what had come before: to keep walking. My feet never stopped hurting, in fact the pain only grew more intense as the days passed. But I feel sort of lucky even for that. I endured, in spite of the pain. It was a lesson to me, perhaps the most important one of all, the very one I went out there to learn: that we can survive even if it nearly kills us.

Can you introduce us to Monster?

Monster is the world’s best backpack, or so I now think. The truth is, we got off to a terrible start. I loaded it up in a motel room in Mojave, California on the morning of the first day of my hike and found that I couldn’t ift it. And I don’t mean I couldn’t hoist it up and on. I mean I couldn’t raise it from the ground. Not even a millimeter. There are many questions I asked myself in the course of my journey, but the first and most serious one was how on this green earth was I going to carry a pack over 1100 miles of mountain wilderness when I couldn’t even lift it an inch in an air-conditioned motel room. My answer was a backpack-donning routine worthy of the most avant-garde modern dance routine you’ve ever seen. It was so humiliating I refused to do it in the presence of others. Which was rather easy, since I seldom saw a soul. Monster is in semi-retirement in my basement now. Whenever I spot it while I’m down there doing the laundry, it’s like running into an old friend. We made that whole journey together. I carried Monster all the way. And it carried me. Of all the profound things I learned on the PCT, I think the most profound was the knowledge that I could bear everything I needed on my own back. That sense of self-sufficiency was unforgettable, both a perspective shift and a life-changer. I couldn’t have done that without Monster. We were a team.

What was the hardest part of the journey — was it the blisters? The dehydrated food? The snow? Or did those pale in comparison to confronting the things that drove you to the trail in the first place?

During my hike, I found there to be an interesting relationship between physical and emotional suffering. Of course the emotional suffering is far more difficult to bear. To keep my mother from dying, I’d have endured the most unendurable physical pain, but I wasn’t given that choice. None of us get to trade this for that. We simply have to do our best given the unchangeable facts of our life. The main fact of my life on the PCT was that I had to walk a really long way every day over challenging terrain in all sorts of weather conditions while carrying an incredibly heavy pack. There was absolutely no arguing with that. Much to my surprise, that fact made the other, more emotional facts more bearable. If I could walk ten miles on blistered feet one hot afternoon, I could go on another day without my mother. The hardest part of my journey was trusting that the days would add up to something bigger than my fears and doubts.

You write about the books you read on the trail. Can you tell us a little about how you selected them and what they meant to you on that trip?

You write about the books you read on the trail. Can you tell us a little about how you selected them and what they meant to you on that trip?

I love books. I’ve always loved books. But the books I took with me on my PCT hike were even more important because they were often my only companions. Some I chose because I’d always heard I should read them — books like Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying and Nabokov’s Lolita fall in to that category — others I chose because I’d already read and loved them, such as Adrienne Rich’s The Dream of Common Language, which is something of a sacred text in Wild.

These many years later are there certain moments or days on the trail that still stay with you more than others?

Some days blur together, others stand out in vivid detail. The agony of hiking with my enormous pack in the tremendous heat of the southern Sierra Nevada is something I’ll never forget. Running out of water on the Hat Creek Rim is another unforgettable experience. I remember those days almost down to the very breaths I took and the steps I made, probably because I felt afraid or uncomfortable. But I also have distinct memories of the trip’s deepest pleasures and smallest joys: the way it felt to eat a cheeseburger at one of my re-supply stops, or to step into a hot shower. I can still feel that ecstasy, like body memory. And of course, the small beautiful moments on the trail, how often I was astonished by the natural beauty all around me. Those things stay with you forever.

How do you think the experience most changed you—both at the time and also are their lessons from the PCT that continue to reveal themselves to you all these years later?

My experience on the PCT gave me a confidence that I don’t think I’d have gotten any other way. It’s a particular kind of confidence — one rooted in humility. How was I going to get from point A to point B? Where would I find clean water? Did I have food and adequate clothing and shelter? Those are the questions that consumed most of my days on the PCT. They mattered more than anything — they always do — but until I was out on the PCT I’d forgotten that. My hike put my priorities in perspective, it reminded me of the power of simplicity, it forced me to be self-sufficient, it tested me physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Over the years, the fruits of that labor have been innumerable.

Who have you discovered lately?

Two debut novelists: Tupelo Hassman, whose breathtaking novel, Girlchild, is beautiful and hard in the best way, and Alexis M. Smith, who wrote a wonderful novel called Glaciers [A Spring 2012 Discover Great New Writers selection. — Ed.] that is so perceptive and precise I found myself slowing down and going back, just so I could read those sentences again.

Cheers, Miwa

Miwa Messer is the Director of the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers program, which was established in 1990 to highlight works of exceptional literary quality that might otherwise be overlooked in a crowded book marketplace. Titles chosen for the program are handpicked by a select group of our booksellers four times a year. Click here for submission guidelines.