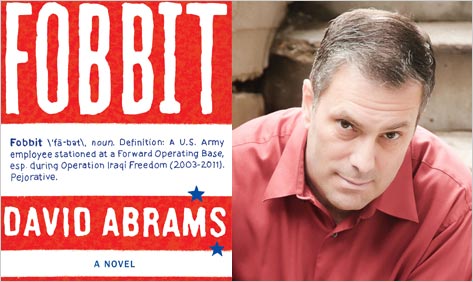

Alternate Histories: David Abrams on Fobbit

“They were Fobbits because, at the core, they were nothing but marshmallow.” So opens David Abrams’s tale of life and death at “Forward Operating Base Triumph,” a fictional version of a real American military base located on the outskirts of Baghdad. But there’s nothing soft in the middle about Fobbit, a wickedly comic story of the surreal days of one Chance Gooding, Jr., infantryman and press release jockey, hunkered down in a cubicle trucked into one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces, pounding out notices of the latest clash with insurgent forces, and trying to keep interfering brass — and the memory of home — at bay.

Abrams knows Gooding’s strange experience of war all too well; in 2005, he was posted to an FOB in Iraq not unlike its imaginary counterpart. The journal he kept while stationed there became the basis of Fobbit, which follows Gooding and a collection of his fellow soldiers — some admirable, some merely competent, some that should be marked “contents under pressure” — through a tour of duty all the more nightmarish for its banality. The result is an achingly funny and deeply honest vision of war’s absurdity in the age of Starbucks and the Internet.

Perhaps because he’s been a frequent contributor to the Review, we were able to convince the author to spend a little time talking with us about his debut work of fiction. From his home in Montana, David Abrams spoke with us via email about Fobbit‘s origin and the classic writing on war that inspired its creation. —Bill Tipper

The Barnes & Noble Review: All of the action in Fobbit takes place in Iraq during the U.S. occupation, but with the exception of a couple of tense scenes on the streets of Baghdad, almost the entirety of the novel is set within the confines of “Forward Operating Base Triumph” — hence the acronym that produces the Tolkienesque nickname for its denizens. And life on the base partakes of a kind of postmodern nightmare of bureaucracy, consumer branding, and bored anxiety. For every soldier who goes out “beyond the wire,” there is another writing a press release in a cubicle.

So the reader’s experience of the story, and the lives of the men you portray, has a curious quality of unreality; they’re in the midst of a lethal, unpredictable combat zone, but what they’re up against looks like something we’ve imported.

David Abrams: I tried to bring an Everyman-Anywhere element to the novel, so I’m glad to see that’s one thing you picked up on. Yes, it’s very particular in its setting — Baghdad, 2005 — but I hope readers will be able to find some familiar points with which to identify. Not everyone’s been to war, but surely most of us have had bosses who steamrolled us with idiocy — whether he’s the manager at the KFC or the self-important guy in HR.

When I first walked in to the task force headquarters on Camp Liberty in Baghdad in 2005, I was struck by how familiar it all felt. I’d been expecting a rougher, more frightening work environment — I mean, what else should I expect when someone says “You’re going to war”? — but here was a cubicle jungle full of bland people hunched over computers working on PowerPoint briefings and filling out spreadsheets. The whole thing screamed Office Space to me. In a sense, I think that’s when the idea for Fobbit germinated. I stood there looking at this gray maze of cubicles, and I realized this wasn’t going to be a typical “war experience.”

BNR: But that familiarity is radically skewed by the fact that violence can penetrate through “the wire” that surrounds the base. In one scene, Chance does the equivalent of a dive into a foxhole — though it’s really just underneath his workstation.

DA: That’s true. The office story is one layer and the combat violence is another. When one pokes through into the other, that’s when the story can get a little jarring. Not unlike what happened to me during my year in Baghdad. I’d be going along doing my job, putting in 14-hour workdays, getting lulled by routine — and then suddenly a mortar would come crashing down on the FOB somewhere. It’s amazing how fast complacency can get stripped away in moments like that. I never dove under my desk, but I probably came close a couple of times.

BNR: A third layer is the sheer absurdity of the environment — which as a literary theme connects Fobbit rather firmly to Catch-22 among other works, but which appears here with amazing specificity. The disgraced infantry captain Abe Shrinkle’s escape to the Australian “prayer meetings” — in which a ribald mixed-sex crew frolic and crack beers poolside — is one example; the contents of his hoarded cache of donated “care packages” is another. How much are those elements based on reality?

DA: On the whole, Fobbit is an example of my imagination running full-bore like an overheated steam engine. Yes, I worked in an Army public affairs office in Baghdad; yes, I turned bland Significant Activity reports into equally bland press releases; yes, I lived like a Fobbit, staying on the FOB nearly the entire time. But when it came time to sit down and write the novel, I knew I needed to turn the volume up to 11 if I wanted readers to stay with me. What was it that Flannery O’Connor said about drawing with “large and startling figures”? If I wanted readers to hear what I had to say, I had to shout through the megaphone of comedy. In the two examples you cite, I can tell you that the Australian pool scenes were entire flights of fancy — yes, there was an Aussie pool which the commanding general eventually put off-limits to U.S. servicemembers, but the topless sunbathers and cold cans of Fosters are entirely mine. As for the hoarded care packages? Well, let’s just say if you’d visited my hooch (the trailer on Camp Liberty where I lived by myself), you would have found an entire wall bricked with tubs of baby wipes. One great thing about the journal I kept that year was the specificity of details I recorded — like the laundry lists of care-package items I received, or the absurd emails from higher headquarters debating the semantics of “terrorist.” When it came time to punch up the narrative, all I had to do was reach back to that journal.

BNR: One of the delights of the book is seeing — in those absurd emails in particular — the application of military thinking and language about strategy and tactics to the task of public relations and media management, as if General Patton were handling press releases.

DA: Well, that was part of the inherent comedy of my day-to-day job over there in Iraq — in my entire 20-year career in Army public relations, really. High-ranking officers who had nothing whatsoever to do with media relations would always try to put their thumbprints on what we did. I guess they thought they could control the press like they maneuvered units on the ground. That’s only going to end in anger and tears of bitterness for those generals. The press is a wild stallion. No matter how hard they tried, military leaders just couldn’t keep it in the corral. Of course, we in public affairs were the middlemen caught in some tough situations. Those scenes where a single press release has to make its way through layers upon layers of approval, delaying its distribution to the media by hours? That was pretty close to the truth. You wouldn’t believe the amount of strategy and groupthink that went into composing a single five-sentence press release. There is an institutional mindset among military leaders — especially those who served in Vietnam — that public affairs belongs at the bottom of the totem pole. It’s getting better these days as military commanders see the press as less of an enemy and more of a tool to shape public perception of the military. Of course, that can lead to even more problems, as we saw in the Pat Tillman and Jessica Lynch situations.

BNR: One of the press-related boondoggles the staff in Fobbit have to contend with is a somewhat ghoulish (from their perspective) press request to be on the scene when a memorable American body count is reached. How exaggerated is that scenario?

DA: Sadly, that’s one of the least hyperbolic passages in the novel. Near the end of my tour in Iraq, the tally of U.S. servicemembers killed in action reached 2,000, and for about a week, our office was busy fielding calls from reporters who wanted to be embedded with Task Force Baghdad units who had a high body count, thus giving them a greater probability of being near the soldier who became the 2,000th casualty. God, it sickens me to even say that out loud, but it’s true. As someone who grew up watching KIA tallies from Vietnam broadcast on the TV screen like baseball scores, this was especially disheartening. Hadn’t the media — and by extension, our society — progressed any farther morally since then? Apparently not. You can probably tell I’m still distressed by the media’s headline fixation on that “landmark death.” It’s one of the few times I think I let my anger bleed over onto the page. It will probably come as no surprise that the diary entry by Chance Gooding, Jr., in which he talks about this is lifted almost word-for-word from my own journal: “The media is drawn like jackals to a watering hole by the number 2,000…. They love the sensuous curve of the 2 and the plump satisfaction of those triple zeroes, lined up like perfect bullet holes — BAM! BAM! BAM!”

BNR: In the novel, those kind of misleading games with representation are played out on multiple levels. If the media is interested in salable abstractions about such “landmarks,” they’re paralleled by the generals who command that the military story about the war must “Put an Iraqi face” on victories, to prop up the illusion that nation-building is proceeding brilliantly. And by Harkleroad’s letters to his mother, which read like pulp fiction of the most improbable kind.

DA: That’s true: deception is multilayered in Fobbit — just as it was in Iraq, and continues to be, out of necessity, in any military conflict. I say “by necessity” because there’s an inherent need for secrecy when you’re at war. You don’t want the enemy to know your vulnerabilities or your next move or even the patterns of thinking which go into plotting your next move. This need for OPSEC (operational security) has been a mainstay of the military for centuries, but it’s more challenging than ever in today’s Web-wired world. More than “challenging” — it’s nearly impossible. So, one of the strategies of offense/defense is a well-crafted press release that can shape the truth, to some degree, of what’s happening in the combat zone. As I say at one point, “Gooding’s weapons were words, his sentences were missiles.” Of course, writing a press release which tells half truths or lies-by-omission creates all sorts of conflict for Gooding. He knows he has to “tell the Army story” (a phrase which was repeatedly drilled into my own head), but how does he square that up with what he knows to be the full truth? Lieutenant Colonel Harkleroad, on the other hand, is so deep into writing his alternate history for his mother that he’s come to believe his own lies.

BNR: It’s hard not to think about Harkleroad’s “alternate history” as a miniature version of other counterfactual narratives that emerged before and during the Iraq conflict — the story of WMDs or that infamous “Mission Accomplished” banner. Fobbit almost tantalizes readers with the hints at a “real” vision of life in occupied Baghdad, glimpsed through fragments of infantry officer Vic Duret’s experience. At one point he reflects on a day’s work that includes negotiations with a local sheik, and one senses the possibility of meaningful engagement with the world outside of the base. But whatever appeal Duret’s working life (as opposed to Gooding’s) has is counterbalanced by the mortal risk and psychic damage combat inflicts. If the world inside the wire is soul deadening, the outside is terrifying.

DA: In the original draft of Fobbit, there were more scenes involving the “reality” of Baghdad — the non-Fobbit world of the conflict. The dissonance between the two worlds was sharply delineated. Some of those chapters set outside the FOB were pretty damn terrifying and, in at least one case, overwhelmingly sad. My editor at Grove/Atlantic, Peter Blackstock, and I ultimately agreed to cut some of those pages — both in the interest of length and to focus the narrative a little more on life inside the FOB. Bear in mind, too, that this novel was written by a Fobbit. My experience and perception of what went on outside the wire is almost entirely based on significant-activity reports we received at task force headquarters, news media accounts, and stories told to me by soldiers who were on missions outside the wire. I hope I got some of it right — at least in spirit, if nothing else.

BNR: That spirit is also a literary one: I want to mention, at this point, a suitably diverting catalogue of names from Fobbit: Lt. Col. Eustace Harkleroad (and his mother Eulalie Constance Harkleroad). Specialist Cinnamon Carnicle. Sgt. Brock Lumley. A doctor called Claspill. The aforementioned Abe Shrinkle and his fledgling replacement Matthew Fledger. Not to mention Abe’s lonely Stateside correspondent Mrs. Norma Tingledecker. It doesn’t seem then all that surprising when Gooding emerges from the bathroom with a copy of Dickens’s Hard Times. (Though there’s also a Pynchonian note in the name of the computer network — the Secure Military Operations Grid, which of course collapses into the acronym SMOG).

DA: For me, the sun rises and sets on Dickens. When it comes to pace, style, and structure of the novel, he’s probably my greatest influence. His choice of names, in particular, is genius. He telegraphs a lot of information about his characters in the way he christens them. He affixes these name-labels to his characters so we’re already forming an opinion about them before they even open their mouths. Noddy Boffin, Jerry Cruncher, Uriah Heep, Charity Pecksniff, Gradgrind, Pumblechook, Dedlock, Fezziwig — I could go on and on. Dickens was a phonetic comedian, and I guess some of that rubbed off on me in my writing — not just in Fobbit but in all of my fiction. Why waste words calling someone Smith when he could be a Harkleroad?

BNR: There were also many novelists and memoirists on American wars that you cite in your acknowledgements: Mailer and Heller of course, as well as Richard Hooker, Tim O’Brien, and your fellow Grove author Karl Marlantes. Do you have a personal favorite among their books?

DA: It’s hard to pick a favorite because each of those books taught me something: Catch-22 showed me it’s okay to laugh at the horror of war; The Naked and the Dead gave me permission to structure a novel episodically with a large cast of characters; The Things They Carried is simply a masterpiece of vibrant language; M*A*S*H, though I read it during final revisions of Fobbit, taught me how to pace jokes (which, in Richard Hooker’s case, is essentially every other sentence); and Matterhorn is an outstanding example of autobiographical fiction — Karl Marlantes is incredibly brave and beautiful in his personal story of Vietnam. One other book which I should mention is Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain. It’s one of the sharpest, “truthiest” novels about America’s attitude toward war that I’ve ever read.

BNR: Have you read any of the recent nonfiction accounts of the war in Iraq?

DA: I steered away from nonfiction accounts of the Iraq War while I was writing Fobbit — the details I had from my limited perspective of the war were my own, and I didn’t want other true stories to seep over into the novel. Near the beginning of writing Fobbit, I did read George Packer’s excellent history of the war’s genesis, The Assassins’ Gate. That should be required reading for anyone who wants to know how we got ourselves into Iraq and, once there, how we took a series of missteps. Since finishing Fobbit, I’ve been delving back into some more war memoirs like Kaboom by Matt Gallagher, What It Is Like to Go to War by Karl Marlantes, and Dust to Dust by Benjamin Busch — each of them excellent in their own way. We can never have too many stories about war, we can never exhaust the ways to tell about how we as individuals and as a nation are shaped by this unnatural experience of combat.