“Be Unafraid”: Edwidge Danticat on Fiction and Memoir

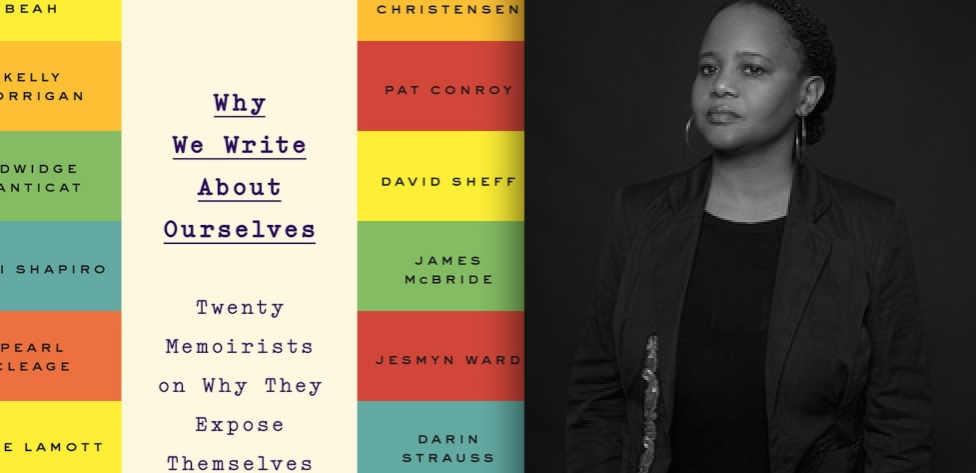

From blog post to status update, we live in an era in which the forms of written self-expression have never been so manifold. But for the writer of memoir, the questions and challenges remain just as they have been since the era of Montaigne: what constitutes the “truth” of a life? When a writer’s days are reshaped on the page to creative narrative, how close should the resulting story map to the reality? And what calls a writer to turn her own experiences into art? These and many other questions are the subject of Meredith Maran’s Why We Write About Ourselves: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature. Writers including Cheryl Strayed, Pat Conroy, Jesmyn Ward, James McBride, Meagan Daum, and others reflect in these conversations on the most intimate and fraught of literary forms.

This week, for the Barnes & Noble Review, award-winning novelist and memoirist Edwidge Danticat (a contributor to Why We Write About Ourselves) spoke with Maran about the places where fiction and memoir intersect, where they diverge, and how novice writers should approach the form.

Meredith Maran: Most of your work is fiction, but you’ve also written the memoir Brother, I’m Dying and essays for several collections. How do you decide which material to use for a novel or short story versus a memoir or personal essay?

Meredith Maran: Most of your work is fiction, but you’ve also written the memoir Brother, I’m Dying and essays for several collections. How do you decide which material to use for a novel or short story versus a memoir or personal essay?

Edwidge Danticat: I know this might sound silly, but I let the material decide. When I write nonfiction, there’s an urgency that makes me want to write it, something I need to get out of my head immediately, something I need to understand a lot better than I do. Though I can’t write nonfiction really fast — I’m not very good at responding immediately — I still write nonfiction a lot faster than I write fiction. Once I have a thread of a thought, a first line, or a clear idea of what I want to say, the rest follows rather quickly, even in long form. Fiction takes a lot longer. And the more fiction I write the longer fiction takes, because I am trying not to repeat myself, not to say the same thing over and over. There’s less of a risk of repeating yourself in nonfiction because often you’re writing about or reacting to something that’s out there in the world, something that’s changing you or has already changed you, even if a little. Nonfiction tends to be more personal, more cathartic for me, even though fiction has that element too.

Edwidge Danticat: I know this might sound silly, but I let the material decide. When I write nonfiction, there’s an urgency that makes me want to write it, something I need to get out of my head immediately, something I need to understand a lot better than I do. Though I can’t write nonfiction really fast — I’m not very good at responding immediately — I still write nonfiction a lot faster than I write fiction. Once I have a thread of a thought, a first line, or a clear idea of what I want to say, the rest follows rather quickly, even in long form. Fiction takes a lot longer. And the more fiction I write the longer fiction takes, because I am trying not to repeat myself, not to say the same thing over and over. There’s less of a risk of repeating yourself in nonfiction because often you’re writing about or reacting to something that’s out there in the world, something that’s changing you or has already changed you, even if a little. Nonfiction tends to be more personal, more cathartic for me, even though fiction has that element too.

MM: Is memoir a popular genre or an anomaly in your native Haiti? Do you face any particular challenges, writing about yourself as a cross-cultural citizen of both Haiti and the U.S.?

Brother, I'm Dying

Brother, I'm Dying

In Stock Online

Paperback $18.00

ED: When I was growing up in Haiti, poetry was used as a form of memoir. Poetry was probably the most direct way the writers I knew of spoke of their personal feelings and things that were going on in their lives. It was poetry first, then the novel. Great men and women who had often been in politics might write their autobiographies, but it was rarely deeply personal. Now some younger writers are writing memoirs. There were a few memoirs, essays, and essay collections published after the 2010 earthquake. Dany Laferrière, a Haitian writer who lives in Canada now, has written what he calls a long autobiography over a dozen books. He writes in this hybrid form that’s part memoir and part fiction, and sometimes reads like poetry. I really like that. There has always been a feeling in my own family that you shouldn’t talk openly about everything. Part of that comes from my parents and older relatives growing up under a dictatorship. In those circumstances, self-revelation was not too helpful, so that’s something my parents have always kept with them. So writing too much about myself is somewhat challenging for me. It feels both hyper-vulnerable and dangerous somehow.

MM: Do you plan to write more fiction or nonfiction going forward?

ED: When I was growing up in Haiti, poetry was used as a form of memoir. Poetry was probably the most direct way the writers I knew of spoke of their personal feelings and things that were going on in their lives. It was poetry first, then the novel. Great men and women who had often been in politics might write their autobiographies, but it was rarely deeply personal. Now some younger writers are writing memoirs. There were a few memoirs, essays, and essay collections published after the 2010 earthquake. Dany Laferrière, a Haitian writer who lives in Canada now, has written what he calls a long autobiography over a dozen books. He writes in this hybrid form that’s part memoir and part fiction, and sometimes reads like poetry. I really like that. There has always been a feeling in my own family that you shouldn’t talk openly about everything. Part of that comes from my parents and older relatives growing up under a dictatorship. In those circumstances, self-revelation was not too helpful, so that’s something my parents have always kept with them. So writing too much about myself is somewhat challenging for me. It feels both hyper-vulnerable and dangerous somehow.

MM: Do you plan to write more fiction or nonfiction going forward?

Why We Write About Ourselves: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature

Why We Write About Ourselves: Twenty Memoirists on Why They Expose Themselves (and Others) in the Name of Literature

Editor Meredith Maran

In Stock Online

Paperback $24.00

ED: I hope to write in every possible genre. I am only half joking when I say that. I like writing in different genres. That keeps a kind of excitement in the process for me. It helps me grow. I have always felt a great sense of excitement about every project I’ve ever undertaken, no matter what the genre. So I hope to explore different genres as I go on, especially ones where I feel less surefooted and less sure of myself. I don’t want to get too complacent, too comfortable, even if I initially fail.

MM: You got an MFA in creative writing from Brown in 1993. How did that and how does that affect your writing and your career? Do you recommend an MFA program for aspiring writers?

ED: I am really glad I got an MFA, but MFA programs are not always easy, especially for writers of color. Brown’s MFA program was, is, a very experimental program, so working with writers like Robert Coover and Meredith Steinbach and the other writers who were in my workshops certainty helped me to learn to push the envelope a little bit. What I most liked was having those two years to concentrate on my writing, to basically live alone and just write and then see some folks in a workshop once a week. That was a great gift. As was being around the poets and playwrights who were in the community. People like Aisha Rahman and C. D. Wright, both of whom have unfortunately recently passed away. Knowing them and the other writers I met in and out of class was really amazing. Seeing a writer’s life in progress, observing up close their love and dedication to their craft was really a great model for me. But I wouldn’t advise anyone to go into debt for an MFA program. Between the class dynamics and the instructors, you never know what you’re going to get. It’s great if you get funding and help to do it. Otherwise, you can try to find groups and workshops and conferences and other types of nurturing communities and replicate that same thing for less.

MM: Your MFA thesis was published as a novel and became an Oprah’s Book Club Selection. How did being tapped by Oprah affect your writing and your career?

ED: I hope to write in every possible genre. I am only half joking when I say that. I like writing in different genres. That keeps a kind of excitement in the process for me. It helps me grow. I have always felt a great sense of excitement about every project I’ve ever undertaken, no matter what the genre. So I hope to explore different genres as I go on, especially ones where I feel less surefooted and less sure of myself. I don’t want to get too complacent, too comfortable, even if I initially fail.

MM: You got an MFA in creative writing from Brown in 1993. How did that and how does that affect your writing and your career? Do you recommend an MFA program for aspiring writers?

ED: I am really glad I got an MFA, but MFA programs are not always easy, especially for writers of color. Brown’s MFA program was, is, a very experimental program, so working with writers like Robert Coover and Meredith Steinbach and the other writers who were in my workshops certainty helped me to learn to push the envelope a little bit. What I most liked was having those two years to concentrate on my writing, to basically live alone and just write and then see some folks in a workshop once a week. That was a great gift. As was being around the poets and playwrights who were in the community. People like Aisha Rahman and C. D. Wright, both of whom have unfortunately recently passed away. Knowing them and the other writers I met in and out of class was really amazing. Seeing a writer’s life in progress, observing up close their love and dedication to their craft was really a great model for me. But I wouldn’t advise anyone to go into debt for an MFA program. Between the class dynamics and the instructors, you never know what you’re going to get. It’s great if you get funding and help to do it. Otherwise, you can try to find groups and workshops and conferences and other types of nurturing communities and replicate that same thing for less.

MM: Your MFA thesis was published as a novel and became an Oprah’s Book Club Selection. How did being tapped by Oprah affect your writing and your career?

Breath, Eyes, Memory

Breath, Eyes, Memory

In Stock Online

Paperback $18.00

ED: Well, more people were able to read my work thanks to Oprah’s Book Club. It was a really great gift in that sense, to be a twenty nine year old writer and have your book on Oprah’s Book Club was just incredible. Oprah introduced me to readers that are still reading me today. That’s very special. And I will always be grateful to her for that.

MM: What was the best thing and the worst thing that happened as a result of publishing your memoir, Brother, I’m Dying?

ED: Nothing bad happened. I felt like I had to write that book. I needed to write it and I got to write it. Of all the books I have written this is the one that feels the most necessary, the one that if no one else ever reads it will remain central to my life, to my family narrative. It’s the book that my children and their children will read to learn about the family, so that means a great deal to me. Brother, I’m Dying was the first nonfiction book chosen for the NEA’s Big Read program. This means that I meet a lot of people who talk about my family with me like we’re old friends. I love that. It’s the best outcome of writing this type of memoir, that people feel so intimately connected to you that you feel like family.

MM: Do you have any advice for memoir writers?

ED: Be bold. Be fearless. Be unafraid. At least while you’re writing the memoir. That’s what I’ve had to keep telling myself to be able to write about myself. Let everything out, even if you take it out later. Censoring yourself during the initial writing, first draft stage might keep you from writing other things. Tell your own truth and keep going until you reach the point where you feel spent, where you feel like you’ve gotten out everything you want to write for that particular project. Then go back and edit them until you get as close as possible to the tone and content of what you want to say.

ED: Well, more people were able to read my work thanks to Oprah’s Book Club. It was a really great gift in that sense, to be a twenty nine year old writer and have your book on Oprah’s Book Club was just incredible. Oprah introduced me to readers that are still reading me today. That’s very special. And I will always be grateful to her for that.

MM: What was the best thing and the worst thing that happened as a result of publishing your memoir, Brother, I’m Dying?

ED: Nothing bad happened. I felt like I had to write that book. I needed to write it and I got to write it. Of all the books I have written this is the one that feels the most necessary, the one that if no one else ever reads it will remain central to my life, to my family narrative. It’s the book that my children and their children will read to learn about the family, so that means a great deal to me. Brother, I’m Dying was the first nonfiction book chosen for the NEA’s Big Read program. This means that I meet a lot of people who talk about my family with me like we’re old friends. I love that. It’s the best outcome of writing this type of memoir, that people feel so intimately connected to you that you feel like family.

MM: Do you have any advice for memoir writers?

ED: Be bold. Be fearless. Be unafraid. At least while you’re writing the memoir. That’s what I’ve had to keep telling myself to be able to write about myself. Let everything out, even if you take it out later. Censoring yourself during the initial writing, first draft stage might keep you from writing other things. Tell your own truth and keep going until you reach the point where you feel spent, where you feel like you’ve gotten out everything you want to write for that particular project. Then go back and edit them until you get as close as possible to the tone and content of what you want to say.