Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? is a graphic memoir — in at least two senses. It joins Muriel Spark’s Memento Mori, William Trevor’s The Old Boys, and Kingsley Amis’s Ending Up in the competition for the funniest book about old age I’ve ever read. It is also heartbreaking. In its pages, the elements of Chast’s most inspired comic work, well known particularly to readers of The New Yorker — impending calamity and aloneness — are no longer mere phantoms but are, instead, intractable, implacable reality. She, an only child, depicts in words, drawings, and ineffable mood her un-self-assured efforts to avert utter disaster as her parents descend into “the part of old age that [is] scarier, harder to talk about, and not part of this culture.”

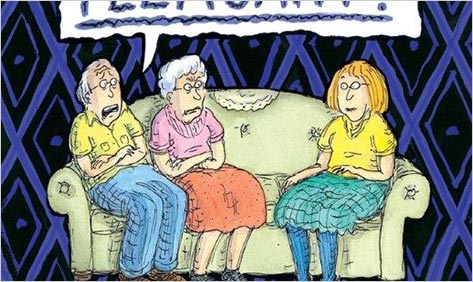

Naturally, this book begins on a doily-accoutered couch, a Chastian fixture as much existential condition as piece of furniture. There we first meet George and Elizabeth Chast, both born in 1912 and now around ninety years old, the two of them stonewalling their daughter’s embarrassed attempt to discuss “things” and, well, you know, “plans.” This endeavor never evolves further than the eventual relief both sides experience in finally escaping the discussion.

In their prime, so to speak, Elizabeth had been an assistant elementary school principal and George, a high school teacher. Both were children of Russian Jews who came to America at the turn of the twentieth century and grew up a few blocks from each other in tenements in East Harlem (“We had nothing!”). They met in the fifth grade and eventually married without having considered anyone else. As a couple, they are perfectly matched: George, passive, patient, gentle, and anxious, is a man who “chain-worried the way others might chain smoke. He never learned to drive, swim, ride a bicycle, or change a lightbulb.” Elizabeth is aggressive, intolerant, confident, and domineering. She writes poetry of sorts, is given to explosions of rage (“blasts from Chast”), and played the piano almost every evening during the author’s unlamented childhood while young Roz and her father “would cower in admiration on the couch.”

The Chasts brought up the author in a dangerous world in “deep” Brooklyn, a world in which you could get infections from mascara or dirty checkers, or go deaf from not wearing a bathing cap, or be killed by a falling flower pot. Laugh during a meal? Choke to death. Fail to dust and it “gets into the interstices of the furniture and BREAKS IT ALL APART!!!” In addition to numbering other such family-endorsed perils, Chast provides a few details about her two grandmothers that one might call diagnostic: George’s mother slept crosswise at the foot of her son’s bed until he married, and she covered all the floors in her apartment with newspaper. Elizabeth’s mother “believed that people on TV could see her.”

By the time Chast manages to get her parents, both now approaching ninety-five, into an assisted living facility (and therein lies a harrowing montage), they have been in the same apartment forty-eight years, deeply disinclined to throw anything out. Chast is confronted with the job of dealing with this monument to pack-rattery and, in tribute, provides an eloquent photo gallery of awe-inspiring vistas of accumulation and select tranches of stuff, including a battalion of her mother’s handbags, a lineup of her glasses “from ‘before my time,” and a “Museum of old Schick shavers.”

As her parents move past their ninety-fifth birthdays, their downhill slide picks up speed, taking on additional indignity and pain. Between the two of them, they have, by the end, suffered dementia, diverticulitis, fistula, incontinence, partial blindness, broken hip, bedsores, pneumonia, and the more routine afflictions of high blood pressure, general weakness, and frailty. The ancient hostility between Chast and her mother becomes more fraught after her father’s death: Roz longing for some sign that her mother had loved her — this mother, now a lunatic version of her old self-centered, chilly self.

Throughout the book, Chast’s drawings express her powerful sense of aloneness. With only a couple of exceptions, it’s just Roz — her daughter appears briefly — faced, as she was as a child, with her parents’ united front: dysfunctional in the past, positively pathological now. Her style — droopy, alarmed, appalled — perfectly captures her overwhelming feeling of inadequacy in the face of this drawn-out emergency. They show, graphically, how events surround her, and how taking care of parents deep in their dotage is an all-encompassing task.

Still, one might think, without really thinking, that a cartoon book about one’s parents’ decline and death would be a breach of good taste: disrespectful and not nice. (Can’t we illustrate something more pleasant?) But, no. The final chapters in both parents’ lives, and their daughter’s bit part in each, are extremely moving. Certainly, the drawings and text are very funny, but here more than anywhere else in Chast’s work, one feels her comedy to be a form of desperate doughtiness, an attempt to foil terror, ease pity, and expiate guilt.