Chuck Palahniuk and Stories You Can’t Unread

Chuck Palahniuk, author of 14 novels including, most famously Fight Club, has been called transgressive, shocking, and an anarchist. His newest book, story collection Make Something Up: Stories You Can’t Unread, doesn’t break that mold. But since Fight Club caught the public imagination in 1996 with its consensual violence and civil discontent, hyper-popular TV shows like Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead have stepped in to push equally disturbing boundaries. Now Palahniuk’s once cultlike appeal seems almost mainstream. Can he still stand out?

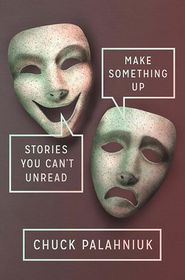

Make Something Up: Stories You Can't Unread

Make Something Up: Stories You Can't Unread

Hardcover $26.95

This book says yes, delivering the punches from its very first story. In “Knock-Knock,” an adult narrator repeats to his dying father all the horrible, racist, sexist jokes the older man used to make him tell as a child at the barber shop, in the hopes of cheering him up. In the process the narrator finally understands that he was, in essence, the punchline to the joke of his father’s life. “And a punchline is called a punchline for a very good reason—because punchlines are a sugar-coated fist with whipped cream hiding the brass knuckles that sock you right in the kisser…”

You might say that quote describes this book, as well. This first story, using a combination of humor and outright absurdity, drives home a dark truth, giving the reader a taste for the stories to come.

Absurdity is one of Palahniuk’s favorite devices for plunging readers into dark psychological waters. Whether he’s telling a suburban creation myth about consumerism, urban despair, and faith, like “How Monkey Got Married, Bought a House, and Found Happiness in Orlando,” or probing the darker recesses of human sexuality, as in “Red Sultan’s Big Boy,” Palahniuk’s magic lies in is his ability to take a harsh and shocking reality and twist till it reveals the pale, tender underbelly of human nature. Beneath every moment of violence lies something innocent, trembling, and begging for the reader’s love or attention.

But Palahniuk doesn’t always rely on sex or violence to get the reader’s attention. One of the more touching stories in this collection is “Eleanor.” Set in either a future time or a parallel universe, the protagonist uses one malapropism after another—misusing words for a jarringly poetic effect:

Randy hate being a nobody. It be like some falling tree already berated him to fractions…The secret truth be the death of Randy daddy. It leave Randy feeling deeply and justifiably defecated.

Rather than making the narrator appear unintelligent, Randy’s tortured efforts at expression have an ennobling quality. In another story, “Torcher,” set in the unnamed but clearly identifiable world of Burning Man, Palahniuk pokes fun at the counterculture ritual while hinting at an understanding of why people go: “What occurred here was a kind of collective Gestalt therapy for the world, and nobody could blame the world for wanting a peek. Monsters capered. Dreams slowly took shape.”

Several stories in the collection touch upon the loss of a father, and it’s hard not to see echoes of Palahniuk’s own history, in which his father, Fred Palahniuk, was murdered by his girlfriend’s ex, Dale Shackleford, in 1999. The brutality and suddenness of that kind of tragedy glimmer at the core of much of his writing. Take a story story like “Zombies,” in which kids give themselves armchair lobotomies via a cardiac defibrillator in the high school nurse’s office to end their suffering. The procedure reduces them to walking ids.

The newspaper warns us about terrorist anthrax bombs and virulent new strains of meningitis, and the only comfort newspapers can offer is a coupon for twenty cents off on underarm deodorant…to have no worries, no regrets? It’s pretty appealing.

It’s hard not to see everything in Palahniuk’s literary universe as a form of social commentary or critique backed by deep emotion—rarely sentimental, but nonetheless full of heart. Of course, just when you think you’ve become comfortable with, or at least used to, the intensity of his boundary pushing, he throws another story at you that crosses from merely disturbing into true morbidity, like “Inclinations.” In this story, a teen pretends to be gay so his parents will send him to a “reorientation camp,” and he can then use his miraculous transformation to pressure his parents into giving him whatever he wants. The story mocks everything from parents’ desires to mold their children to social prejudices against homosexuality, with a little necrophilia thrown in.

This is the same author who took pride in making audiences faint when he read aloud his gory story “Guts.” Pahlaniuk seems to operate on the premise that in a society where people are so easily desensitized, sometimes you have to shout. There is no topic too sacred for Palahniuk to touch. In “Expedition,” he even quotes the Marquis de Sade in the epigraph: “In order to know virtue we must first acquaint ourselves with vice.”

Despite the many wild turns down rabbit holes you’ve probably never considered, you can almost hear Palahniuk giggling in the background, amused at his own daring, taking pleasure in the reader’s inability to turn away. His characters and their situations may be extreme, but they are only human after all.

Shop All New Releases

This book says yes, delivering the punches from its very first story. In “Knock-Knock,” an adult narrator repeats to his dying father all the horrible, racist, sexist jokes the older man used to make him tell as a child at the barber shop, in the hopes of cheering him up. In the process the narrator finally understands that he was, in essence, the punchline to the joke of his father’s life. “And a punchline is called a punchline for a very good reason—because punchlines are a sugar-coated fist with whipped cream hiding the brass knuckles that sock you right in the kisser…”

You might say that quote describes this book, as well. This first story, using a combination of humor and outright absurdity, drives home a dark truth, giving the reader a taste for the stories to come.

Absurdity is one of Palahniuk’s favorite devices for plunging readers into dark psychological waters. Whether he’s telling a suburban creation myth about consumerism, urban despair, and faith, like “How Monkey Got Married, Bought a House, and Found Happiness in Orlando,” or probing the darker recesses of human sexuality, as in “Red Sultan’s Big Boy,” Palahniuk’s magic lies in is his ability to take a harsh and shocking reality and twist till it reveals the pale, tender underbelly of human nature. Beneath every moment of violence lies something innocent, trembling, and begging for the reader’s love or attention.

But Palahniuk doesn’t always rely on sex or violence to get the reader’s attention. One of the more touching stories in this collection is “Eleanor.” Set in either a future time or a parallel universe, the protagonist uses one malapropism after another—misusing words for a jarringly poetic effect:

Randy hate being a nobody. It be like some falling tree already berated him to fractions…The secret truth be the death of Randy daddy. It leave Randy feeling deeply and justifiably defecated.

Rather than making the narrator appear unintelligent, Randy’s tortured efforts at expression have an ennobling quality. In another story, “Torcher,” set in the unnamed but clearly identifiable world of Burning Man, Palahniuk pokes fun at the counterculture ritual while hinting at an understanding of why people go: “What occurred here was a kind of collective Gestalt therapy for the world, and nobody could blame the world for wanting a peek. Monsters capered. Dreams slowly took shape.”

Several stories in the collection touch upon the loss of a father, and it’s hard not to see echoes of Palahniuk’s own history, in which his father, Fred Palahniuk, was murdered by his girlfriend’s ex, Dale Shackleford, in 1999. The brutality and suddenness of that kind of tragedy glimmer at the core of much of his writing. Take a story story like “Zombies,” in which kids give themselves armchair lobotomies via a cardiac defibrillator in the high school nurse’s office to end their suffering. The procedure reduces them to walking ids.

The newspaper warns us about terrorist anthrax bombs and virulent new strains of meningitis, and the only comfort newspapers can offer is a coupon for twenty cents off on underarm deodorant…to have no worries, no regrets? It’s pretty appealing.

It’s hard not to see everything in Palahniuk’s literary universe as a form of social commentary or critique backed by deep emotion—rarely sentimental, but nonetheless full of heart. Of course, just when you think you’ve become comfortable with, or at least used to, the intensity of his boundary pushing, he throws another story at you that crosses from merely disturbing into true morbidity, like “Inclinations.” In this story, a teen pretends to be gay so his parents will send him to a “reorientation camp,” and he can then use his miraculous transformation to pressure his parents into giving him whatever he wants. The story mocks everything from parents’ desires to mold their children to social prejudices against homosexuality, with a little necrophilia thrown in.

This is the same author who took pride in making audiences faint when he read aloud his gory story “Guts.” Pahlaniuk seems to operate on the premise that in a society where people are so easily desensitized, sometimes you have to shout. There is no topic too sacred for Palahniuk to touch. In “Expedition,” he even quotes the Marquis de Sade in the epigraph: “In order to know virtue we must first acquaint ourselves with vice.”

Despite the many wild turns down rabbit holes you’ve probably never considered, you can almost hear Palahniuk giggling in the background, amused at his own daring, taking pleasure in the reader’s inability to turn away. His characters and their situations may be extreme, but they are only human after all.

Shop All New Releases