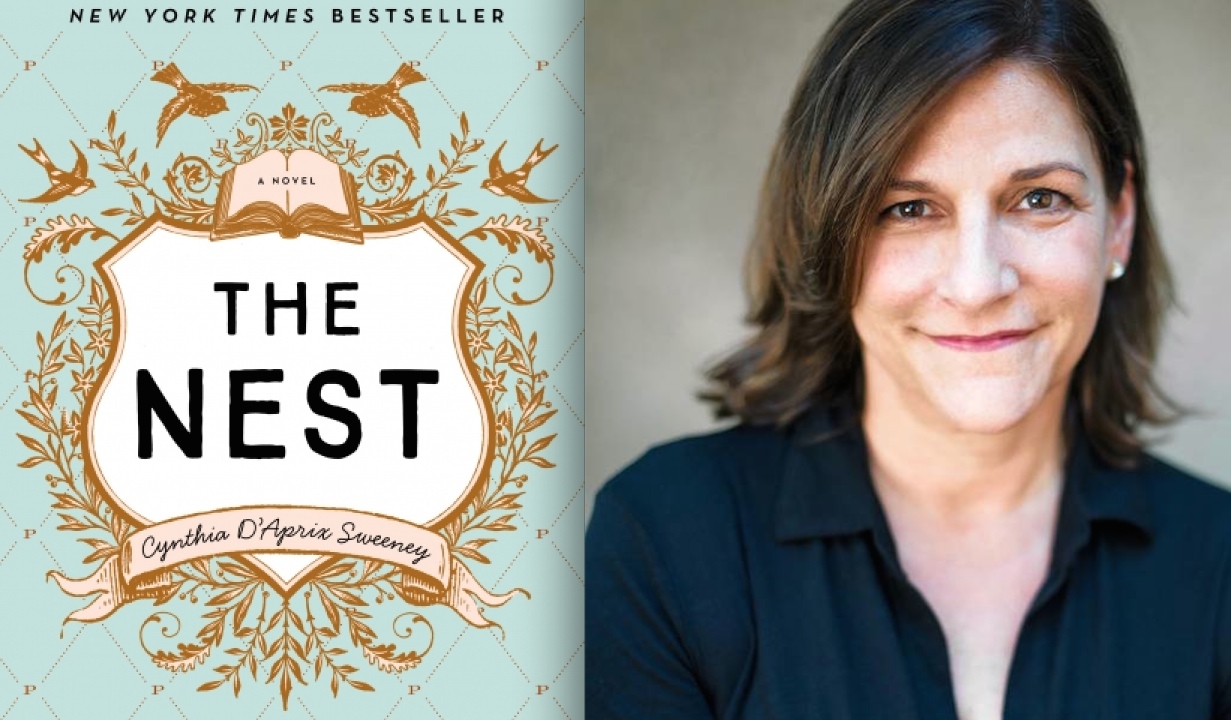

Love and Money: Cynthia Sweeney Talks “The Nest” with Susan Orlean

We spend holidays looking across the table and thinking, “Do we actually share DNA? Were we raised by wolves? Were we raised by the same wolves?” Four siblings, one inheritance. Each of the Plumbs made plans for his or her piece of the nest, and luckily for readers, Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney knows how to find the humor in family relationships and best-laid plans run off the rails. Anything and everything that can go wrong, does, in The Nest, a witty and poignant story of family and money, secrets and love, growing up, and finding home. And just wait until you meet Mama Plumb.

In a recent conversation at the Grove in Los Angeles, Sweeney spoke with Susan Orlean, a staff writer for the New Yorker and the bestselling author of eight books, including The Bullfighter Checks Her Makeup, My Kind of Place, Saturday Night, Lazy Little Loafers, and the New York Times bestseller Rin-Tin-Tin: The Life and Legend. In 1999 she published The Orchid Thief, a narrative about orchid poachers in Florida, which was made into the Academy Award−winning film Adaptation, written by Charlie Kaufman and directed by Spike Jonze. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation. — Miwa Messer

Susan Orlean: Family, as we began, is obviously at the heart of The Nest, as it is, I think, the story of all literature, frankly, whether it’s your birth family, a family you create, or your place in the family of humankind. So the book resonates on so many levels, just this notion of trying to fit in and trying to make your peace. So tell me, where are you in your birth order, and where was it in your life in terms of your growth? Was being part of a family and a place in a birth order important to you?

Cynthia D’Aprix Sweeney: Well, I am the oldest. So I was in charge. [Laughs]

SO: Oldest of how many?

CS: Four. Oddly enough. But you know, I think everyone sort of feels the burden of their place. I can speak very poignantly about the burden of being the oldest, and my siblings would each have their own stories, and they definitely think that I had the sweet spot.

SO: And did you?

CS: I don’t know. My parents were really young when they had me, and they were terrified. They just were very worried, and I couldn’t do anything, and they were very strict and they were cautious, so by the time my brother, who is eleven years younger than I am, was growing up, he literally had a completely different childhood. I think that’s what really happens in families where there are more than one, but even probably more than two kids — you have this running tally of what your childhood was compared to everyone else’s childhood.

CS: I don’t know. My parents were really young when they had me, and they were terrified. They just were very worried, and I couldn’t do anything, and they were very strict and they were cautious, so by the time my brother, who is eleven years younger than I am, was growing up, he literally had a completely different childhood. I think that’s what really happens in families where there are more than one, but even probably more than two kids — you have this running tally of what your childhood was compared to everyone else’s childhood.

SO: On one hand you believe you were born into the same family, but in fact, each of you is born into a family defined by a moment.

You had very young parents. Your brother, who is eleven years younger, didn’t have such young parents.

The Nest

The Nest

Hardcover $26.99

CS: Right. He had parents who were financially in a better place. For one of my parents’ wedding anniversaries, when he was quite young, he took a wine bottle and he cut out things from a magazine, and decoupaged them — Paris, Rome, London, pictures of Big Ben. My sister and my other brother and I looked at it, and we were like, “What family did you grow up in? We went to Toronto or somewhere, and stayed at the Don Valley Inn, and your vacation memories are, you know, Big Ben. But we were all in college, and my dad was traveling for work, and my youngest brother just sort of went along for the ride,so he has a different relationship with them than the other three of us do.

SO: Did you grow up thinking about the dynamics of family? Or was this something when you decided to start writing fiction that you began kind of digging back into that part of your psyche?

CS: I grew up in a very Irish-Italian Catholic environment — every family had tons of kids. In fact, one of the first things you would say to someone when you met them was, “How many in your family?” What you meant was, “How many kids?” My answer would always be, “Oh, we have a small family.” Because there were just four of us. Because we did have a small family. So I was obsessed with the houses that had five-six-seven-eight-ten kids, and I loved going over there, and I always wished I had an older brother. I somehow fantasized that he would magically pave the way for everything.

SO: I have an older brother, and I can tell you that’s not true.

CS: So I have always been fascinated by sibling relationships. And I still have a lot of friends, some of them in this room, who have a lot of siblings, and those relationships become ever more fraught as you get older, and everyone’s lives start to diverge, and parents age — it’s complicated. And there is kind of this cultural assumption that, well, family’s family; you love them no matter what.

SO: One thing that I really loved the book is that acknowledgment that you are going to be with your siblings longer than you will be with your parents.

CS: Yes.

SO: When you look at the kids in this family, each one is so different, and they do remain connected in a way, but they are constantly having to reinvent their relationship.

CS: Right. I don’t think it’s a book about money. I think it’s a book about family, and money is the fictional device that puts pressure on the family: I think it’s about a family in peril. It’s about family members who are struggling individually and they’re struggling as a unit, and money is the thing that puts pressure on those relationships so that you get a story.

But the real inheritance that everyone has is being born into a story that you have no control over. You are born into somebody else’s story. You just become the oldest-the-youngest-the middle, and as your family grows and life goes on, and I think parents tend to assign very reductive descriptors to people that stick. You’re “the smart one,” you’re “the clumsy one,” you’re “the jock,” you’re “the funny one.” It’s really hard to break out of that narrative and create your own one. We’re meeting these characteres at the moment in their lives when they have to figure out how to reconcile their inheritance — which is not just money, especially since it’s gone, but is story — with the story they want to create.

SO: It is funny how, even at their very advanced age, the label still sticks. The one who is troubled. The one who is the studious one. It doesn’t really change — first of all, it’s often true. And second, no matter how much you might change, you will remain labeled that way.

CS: Right. And you will feel yourself seen that way.

SO: One thing that I think we’ve talked about is that the minute you’re with your siblings, it’s like time-travel where you’re back to being a totally immature eight-year-old. It’s embarrassing.

CS: Yes. It’s literally like, “That’s my chair.” Or “I’m not sitting in the middle.” It’s incredible. In a way, it’s slightly kind of heartening to think, oh, you can be ten years old again.

SO: It’s a familiar groove that you can get right back into — there’s something enjoyable about it.

CS: In a totally sick way. The way that an argument can escalate is still astonishing to me. It takes four sentences for everyone in the room to be so pissed at each other that no one speaks for the rest of the night.

SO: Yes. Aren’t families great? What are some of the books that you looked to as models of looking at family relationships?

CS: Definitely The Corrections. That was a book that I went to a lot in terms of structure and sort of how to go back and forth between different people’s stories. I love Tessa Hadley, and she writes really complicated struggling families. There’s a great book that came out right when I started this one by Joshua Henkin . . .

SO: Did you look at any of these as models particularly, or just for inspiration?

CS: I think once I started, once I was really into the book, I realized that I was writing it in rotating point of view, I did start looking for books that were written in rotating point of view. If it was a family sequence, then that was better. It was more trying to solve how to move through time and how to move among all these characters without people getting impatient and losing the thread. Like, how long I could drop a character before you’d start to get impatient or lose the thread of that person.

SO: And sort of wonder where they were.

CS: Yes.

SO: It’s a very different thing to write about adults and family order, versus children. Was that a choice you made, that you were going to focus on that part of the idea of family?

CS: I don’t think it was a conscious choice. I’m not sure I would have known how to write about a group of adult siblings without that being an element of their story. Because I think it’s really unusual for anyone to be able to escape that. I read, not for this book, but years ago a couple of books on sibling relationships and birth order, and the most fascinating thing is that those behaviors that you acquire based on your birth order don’t really exist when you’re out in the world, but the minute you’re back with your family . . .

SO: So it’s relational?

CS: Yes.

SO: Did you look at sort of pop science about birth order? I say “pop science” because some of it is a little simplified, I think.

CS: I didn’t. I sort of already knew, like, what the tropes were. But the reason I chose to write about four siblings is because I am one of four, and I understood that dynamic. In fact, when I started the book, there were only three, and I had to add another one, because that’s just what’s in my bones as to how a group reacts, and group dynamics.

SO: Until you said that, it hadn’t occurred to me: I am from a family of three kids, and so it took me some adjustment mentally, because, of course, I was trying to see who in the family was which of my siblings, and who was awesome enough to be me. And not having an additional sibling, it actually took some adjustment. It was more evidence to me of how deeply imprinted we are by our particular family.

CS: Yes.

SO: How have your siblings responded to the book?

CS: They love the book. It’s not about them. So they are very relieved! [Laughs] I think they were a little worried.

SO: So even though you say the book is about family (and for me, it certainly was), it’s also additionally very much the story of money, and its complicated effect on our lives.

CS: Yes.

SO: You made the comment that your parents were in a different financial situation when you were growing up than at the point your youngest brother was. But how has it been a topic that you’ve grappled with?

CS: In my family?

SO: In your family and thinking about it. I mean, I think about it all the time. I think about money pretty much twenty-four hours a day.

CS: Really? I think about food.

SO: I actually think about sex, but I didn’t want to say that. But we’ve now hit all three major points. So we’re good.

CS: I think that my obsession with observing money and how it affects people didn’t come out of my family experience really. It came out of living in New York for twenty-five years and having grown up in a very middle-class suburb. I thought when I was growing up that trust funds and inheritances were things in books and movies and Great Britain. Then I moved to New York City and discovered that they were real. It’s interesting. It’s just interesting to me to see what happens when you’re an adult, and there is a source of money in your life that is not work. It does things to you. I knew people who handled it very graciously and wonderfully and people who didn’t. I think it really complicated your relationship with your parents if you’re still receiving funds from them once you are trying to live your own life.

SO: I want to get nerdy and talk about writing itself. I am particularly fascinated because I don’t write fiction, so some of this is the sort of curiosity of how it develops in contrast to writing nonfiction. To begin with, I’m very curious if you conceived of the book and laid it out in your mind, or whether it was something that unfurled on the page, or a combination.

CS: It was a combination. I was in graduate school, and I thought I was working on a short story about these characters, and I said to my thesis advisor, “It’s terrible, it’s not working. It’s thirty-five pages of a beginning, and no middle, and four pages of a crappy ending.” He said, “Well, it’s not a short story. It’s the beginning of a novel. How about we do this for the next three months?” The first question I asked him was, “How much do I have to know about the end?” He said, “You don’t need to know anything, but it would help you if you knew where you want to leave each character off, where they will end up emotionally. That will be your guiding light.”

SO: And it was these characters.

CS: It was these characters, and the story was sort of the first chapter of the book. It was all the siblings getting together for lunch and confronting Leo. So I just started writing. I started rotating through people, and really inching along. Then there came a point, maybe a little more than halfway through, where I could see what was going to happen. I could see how all the strands were going to come together, and where I was going to bring everyone, and how everyone’s story was going to end. That’s when the writing becomes a lot less fun, because you’re just playing out the inevitable. You still surprise yourself during that time, but at the beginning you’re really surprising yourself. And you have to get through to the end, and then you can go back and look at it all. This, I think, applies to whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction — then you see the things that have happened that you can make better, and things you can bring back or bring forward or weave through, where the really interesting things are that you maybe turn up the volume on a little bit. But you have to get through that first draft.

SO: So you start at the beginning and write through.

CS: Yeah. Sometimes, because I was writing in different characters, I would jump ahead with someone’s story, and then have to go back. There were a lot of Post-It notes and a lot of color-coded pencils and index cards and stuff.

SO: Did you know from the beginning that you would set it in New York, even though at that point you were living in L.A.? Why did you make that choice?

CS: Practically everything I started writing in graduate school took place in New York. I had only been living in L.A. for a couple of years, and I still felt like it was someplace I was vacationing. So the place that I know, the place that I feel comfortable in, the place I feel confident writing about is New York.

SO: Of the clichés that people say about cities, New York is very much about money. . .

CS: Yes. In a very different way than Los Angeles.

SO: Also, if you’re going to make these broad generalizations about rootlessness and disconnection from family, and New York feels so much . . I could see this also based in Boston for that same reason.

CS: Right. I think it is a very northeastern type of story.

SO: I have a feeling there are people in L.A. with families. Just guessing! But as a kind of backdrop to a story like this, it would have been very different.

CS: I think also people in New York are so set in their ways and in their preferences, and that has to do with family stuff in a way that doesn’t seem to happen here, because so many people come from somewhere else. You don’t have the restaurant you go to every Christmas Eve: “This is where we go, this is how we do . . . ”

SO: Right. You don’t have your mother’s rent-controlled apartment.

CS: Right. Which God forbid you give up. You will cram seventeen people into that apartment because you have it. I think, too, that part of what’s true for three of the siblings in this story is just that sense that, when you live in New York — if you figure out a way to live in New York, it feels like such an accomplishment. It’s such a hard place to live and especially decide to have your kids and have a family. And when you figure it out, the thought of losing it, the thought of letting go of it seems like such a failure, and you make compromises and decisions that maybe you shouldn’t just to stay where you are. Because losing ground in New York . . . it really hurts.

SO: When I think of my office, it is just piled with notes, with research, with materials. So I pictured you sitting at a very tidy desk, having your imaginary friends in your head kind of directing the story. But it sounds like at least you had Post-It notes.

CS: I had a huge bulletin board. I like to see things, the chapters plotted out. Also I was juggling these characters, and I was juggling the Plumb family, and I was juggling peripheral characters, so they had two different-color Post-It notes. I was keeping track — if I saw, “Oh, I have too many blue chapters in a row; I need to get a pink one in there.” Then I had an index. It was a mess.

SO: Were there any major characters or major tropes in the book that you ended up cutting out?

CS: When I started the book, I was in an MFA program, and I knew that one of the characters was going to be a writer, and I just thought, “I cannot make her a fiction writer; that is not something that you are supposed to do; it is a no-no; you are not supposed to show up in workshop with a novel with a character who can’t write a novel.” When someone does, you can just feel the entire room go, “Oh . . . ” So I somehow thought it would be a good idea to make her a poet. And she was a poet throughout the entire first draft.

SO: Oh, really.

CS: My thesis advisor and now friend — no-bullshit friend — read the first draft, and kind of while he was reading things, he was, like, “The point being . . . Are the stakes really that high for her for poetry?” But we came up with some ideas. He was like, “OK, maybe if you do this and maybe if you do that.” He read the first draft, and he just said, “It’s not working; she has to write something else.” I landed on the idea of her having been a short story writer and having written these stories about her brother Leo, and had become successful very young and then lost her touch. As soon as I made that decision, I was really excited about it, and as soon as I started writing Bea as a fiction writer, literally the entire book came up, and everything came together, and it solved all kinds of little connectivity problems. They are among my favorite chapters, and they were the most fun to write.

So I have to remind myself that really the only time in this process that I made a decision based on worrying about selling the book, it was the wrong decision.

SO: This will sound like a funny question. But did you do what you set out to do with the book? Did you feel when you were done that it had achieved what you were hoping for?

CS: Yes. I think I wrote the book that I wanted to write. Someone asked me last night if I felt like, “Oh, this is it; I love it; it’s perfect.” And I don’t. I feel like it’s the best version of this book I could write when I wrote it, and I’m proud of it, but even when I’ve been reading over the past few nights, all my pages are marked up.

SO: Did you edit a lot? I mean, you mentioned the first draft, and I know you worked through this quite a bit. How much of an editor are you of your own work? Do you throw stuff out?

CS: I throw so much stuff out. I worked as a nonfiction writer for many-many-many years, and I was writing stuff that wasn’t mine, that I didn’t have ownership of, and so I became very accustomed to kind of detaching from it. So yes, I threw out tons of stuff. I think I am a really good editor, and I went through the manuscript many-many-many times before I started clearing agents, or before it went out to publishers. I’m pretty anal about editing.

SO: This is maybe partly speculative. But what do you feel has connected for a reader? What part of it did you write imagining how it would feel being read, and what has been your experience now that you’re out in the world with how people are responding? It’s interesting that you say it’s a book about family, not a book about money, and yet some people may read it . . .

CS: Yes, I may be the only person who thinks that way!

SO: I remember once writing something that I thought was really depressing, and having someone say, “I just finished your piece; it was so fun.” I thought, “Wow!” The fact is, this is out in the world now. People will respond to it on their own. But what’s that been like for you, and what have you found that’s surprised you?

CS: That everyone wants to talk to me about money and trusts and inheritances, and they want me to tell them whether or not it’s a good idea to leave money to their children.

SO: Oh my God, so this has really turned into a financial literacy book.

CS: Yes. It’s like, Rich Dad, Poor Dad or something. I have no idea. I literally have no advice to give you! In almost every interview someone has said, “So, do you think it’s a good idea or a bad idea for parents to leave money to their children?” That has taken me by surprise.

SO: One thing that’s amazing about a book is that after you’ve birthed it, it really is its own entity, it has its own life. I remember that when I was on my book tour for The Orchid Thief, and I took a question at a reading, and someone said, “I have a Phalaenopsis that doesn’t look good; do you have any . . . ” I thought, “I failed totally if you think, first of all, if you think I know anything about taking care of orchids, but also if that’s what you think this book is about.” But then I thought that’s what reading is, in a way — and that someone should read it is a joy.

CS: I think it’s cool. Six weeks ago, I would have said, “This is a book about family, and that’s why people connect to it.” I can tell you now that people connect to it because it’s about money, and people are fascinated by money.

SO: I am sort of filled with awe about the idea that I created something, but it’s independent of me, and that someone can read it and have a completely individual reaction that I am not even controlling.

CS: Yes. It’s a transaction between the reader and the book that has nothing to do with you, and that’s very cool.

SO: Even if they think it’s about how to invest in a 401(k), it’s OK. It’s just different.

CS: I know. “What’s that thing for college tuition? Do that.”

CS: Right. He had parents who were financially in a better place. For one of my parents’ wedding anniversaries, when he was quite young, he took a wine bottle and he cut out things from a magazine, and decoupaged them — Paris, Rome, London, pictures of Big Ben. My sister and my other brother and I looked at it, and we were like, “What family did you grow up in? We went to Toronto or somewhere, and stayed at the Don Valley Inn, and your vacation memories are, you know, Big Ben. But we were all in college, and my dad was traveling for work, and my youngest brother just sort of went along for the ride,so he has a different relationship with them than the other three of us do.

SO: Did you grow up thinking about the dynamics of family? Or was this something when you decided to start writing fiction that you began kind of digging back into that part of your psyche?

CS: I grew up in a very Irish-Italian Catholic environment — every family had tons of kids. In fact, one of the first things you would say to someone when you met them was, “How many in your family?” What you meant was, “How many kids?” My answer would always be, “Oh, we have a small family.” Because there were just four of us. Because we did have a small family. So I was obsessed with the houses that had five-six-seven-eight-ten kids, and I loved going over there, and I always wished I had an older brother. I somehow fantasized that he would magically pave the way for everything.

SO: I have an older brother, and I can tell you that’s not true.

CS: So I have always been fascinated by sibling relationships. And I still have a lot of friends, some of them in this room, who have a lot of siblings, and those relationships become ever more fraught as you get older, and everyone’s lives start to diverge, and parents age — it’s complicated. And there is kind of this cultural assumption that, well, family’s family; you love them no matter what.

SO: One thing that I really loved the book is that acknowledgment that you are going to be with your siblings longer than you will be with your parents.

CS: Yes.

SO: When you look at the kids in this family, each one is so different, and they do remain connected in a way, but they are constantly having to reinvent their relationship.

CS: Right. I don’t think it’s a book about money. I think it’s a book about family, and money is the fictional device that puts pressure on the family: I think it’s about a family in peril. It’s about family members who are struggling individually and they’re struggling as a unit, and money is the thing that puts pressure on those relationships so that you get a story.

But the real inheritance that everyone has is being born into a story that you have no control over. You are born into somebody else’s story. You just become the oldest-the-youngest-the middle, and as your family grows and life goes on, and I think parents tend to assign very reductive descriptors to people that stick. You’re “the smart one,” you’re “the clumsy one,” you’re “the jock,” you’re “the funny one.” It’s really hard to break out of that narrative and create your own one. We’re meeting these characteres at the moment in their lives when they have to figure out how to reconcile their inheritance — which is not just money, especially since it’s gone, but is story — with the story they want to create.

SO: It is funny how, even at their very advanced age, the label still sticks. The one who is troubled. The one who is the studious one. It doesn’t really change — first of all, it’s often true. And second, no matter how much you might change, you will remain labeled that way.

CS: Right. And you will feel yourself seen that way.

SO: One thing that I think we’ve talked about is that the minute you’re with your siblings, it’s like time-travel where you’re back to being a totally immature eight-year-old. It’s embarrassing.

CS: Yes. It’s literally like, “That’s my chair.” Or “I’m not sitting in the middle.” It’s incredible. In a way, it’s slightly kind of heartening to think, oh, you can be ten years old again.

SO: It’s a familiar groove that you can get right back into — there’s something enjoyable about it.

CS: In a totally sick way. The way that an argument can escalate is still astonishing to me. It takes four sentences for everyone in the room to be so pissed at each other that no one speaks for the rest of the night.

SO: Yes. Aren’t families great? What are some of the books that you looked to as models of looking at family relationships?

CS: Definitely The Corrections. That was a book that I went to a lot in terms of structure and sort of how to go back and forth between different people’s stories. I love Tessa Hadley, and she writes really complicated struggling families. There’s a great book that came out right when I started this one by Joshua Henkin . . .

SO: Did you look at any of these as models particularly, or just for inspiration?

CS: I think once I started, once I was really into the book, I realized that I was writing it in rotating point of view, I did start looking for books that were written in rotating point of view. If it was a family sequence, then that was better. It was more trying to solve how to move through time and how to move among all these characters without people getting impatient and losing the thread. Like, how long I could drop a character before you’d start to get impatient or lose the thread of that person.

SO: And sort of wonder where they were.

CS: Yes.

SO: It’s a very different thing to write about adults and family order, versus children. Was that a choice you made, that you were going to focus on that part of the idea of family?

CS: I don’t think it was a conscious choice. I’m not sure I would have known how to write about a group of adult siblings without that being an element of their story. Because I think it’s really unusual for anyone to be able to escape that. I read, not for this book, but years ago a couple of books on sibling relationships and birth order, and the most fascinating thing is that those behaviors that you acquire based on your birth order don’t really exist when you’re out in the world, but the minute you’re back with your family . . .

SO: So it’s relational?

CS: Yes.

SO: Did you look at sort of pop science about birth order? I say “pop science” because some of it is a little simplified, I think.

CS: I didn’t. I sort of already knew, like, what the tropes were. But the reason I chose to write about four siblings is because I am one of four, and I understood that dynamic. In fact, when I started the book, there were only three, and I had to add another one, because that’s just what’s in my bones as to how a group reacts, and group dynamics.

SO: Until you said that, it hadn’t occurred to me: I am from a family of three kids, and so it took me some adjustment mentally, because, of course, I was trying to see who in the family was which of my siblings, and who was awesome enough to be me. And not having an additional sibling, it actually took some adjustment. It was more evidence to me of how deeply imprinted we are by our particular family.

CS: Yes.

SO: How have your siblings responded to the book?

CS: They love the book. It’s not about them. So they are very relieved! [Laughs] I think they were a little worried.

SO: So even though you say the book is about family (and for me, it certainly was), it’s also additionally very much the story of money, and its complicated effect on our lives.

CS: Yes.

SO: You made the comment that your parents were in a different financial situation when you were growing up than at the point your youngest brother was. But how has it been a topic that you’ve grappled with?

CS: In my family?

SO: In your family and thinking about it. I mean, I think about it all the time. I think about money pretty much twenty-four hours a day.

CS: Really? I think about food.

SO: I actually think about sex, but I didn’t want to say that. But we’ve now hit all three major points. So we’re good.

CS: I think that my obsession with observing money and how it affects people didn’t come out of my family experience really. It came out of living in New York for twenty-five years and having grown up in a very middle-class suburb. I thought when I was growing up that trust funds and inheritances were things in books and movies and Great Britain. Then I moved to New York City and discovered that they were real. It’s interesting. It’s just interesting to me to see what happens when you’re an adult, and there is a source of money in your life that is not work. It does things to you. I knew people who handled it very graciously and wonderfully and people who didn’t. I think it really complicated your relationship with your parents if you’re still receiving funds from them once you are trying to live your own life.

SO: I want to get nerdy and talk about writing itself. I am particularly fascinated because I don’t write fiction, so some of this is the sort of curiosity of how it develops in contrast to writing nonfiction. To begin with, I’m very curious if you conceived of the book and laid it out in your mind, or whether it was something that unfurled on the page, or a combination.

CS: It was a combination. I was in graduate school, and I thought I was working on a short story about these characters, and I said to my thesis advisor, “It’s terrible, it’s not working. It’s thirty-five pages of a beginning, and no middle, and four pages of a crappy ending.” He said, “Well, it’s not a short story. It’s the beginning of a novel. How about we do this for the next three months?” The first question I asked him was, “How much do I have to know about the end?” He said, “You don’t need to know anything, but it would help you if you knew where you want to leave each character off, where they will end up emotionally. That will be your guiding light.”

SO: And it was these characters.

CS: It was these characters, and the story was sort of the first chapter of the book. It was all the siblings getting together for lunch and confronting Leo. So I just started writing. I started rotating through people, and really inching along. Then there came a point, maybe a little more than halfway through, where I could see what was going to happen. I could see how all the strands were going to come together, and where I was going to bring everyone, and how everyone’s story was going to end. That’s when the writing becomes a lot less fun, because you’re just playing out the inevitable. You still surprise yourself during that time, but at the beginning you’re really surprising yourself. And you have to get through to the end, and then you can go back and look at it all. This, I think, applies to whether you’re writing fiction or nonfiction — then you see the things that have happened that you can make better, and things you can bring back or bring forward or weave through, where the really interesting things are that you maybe turn up the volume on a little bit. But you have to get through that first draft.

SO: So you start at the beginning and write through.

CS: Yeah. Sometimes, because I was writing in different characters, I would jump ahead with someone’s story, and then have to go back. There were a lot of Post-It notes and a lot of color-coded pencils and index cards and stuff.

SO: Did you know from the beginning that you would set it in New York, even though at that point you were living in L.A.? Why did you make that choice?

CS: Practically everything I started writing in graduate school took place in New York. I had only been living in L.A. for a couple of years, and I still felt like it was someplace I was vacationing. So the place that I know, the place that I feel comfortable in, the place I feel confident writing about is New York.

SO: Of the clichés that people say about cities, New York is very much about money. . .

CS: Yes. In a very different way than Los Angeles.

SO: Also, if you’re going to make these broad generalizations about rootlessness and disconnection from family, and New York feels so much . . I could see this also based in Boston for that same reason.

CS: Right. I think it is a very northeastern type of story.

SO: I have a feeling there are people in L.A. with families. Just guessing! But as a kind of backdrop to a story like this, it would have been very different.

CS: I think also people in New York are so set in their ways and in their preferences, and that has to do with family stuff in a way that doesn’t seem to happen here, because so many people come from somewhere else. You don’t have the restaurant you go to every Christmas Eve: “This is where we go, this is how we do . . . ”

SO: Right. You don’t have your mother’s rent-controlled apartment.

CS: Right. Which God forbid you give up. You will cram seventeen people into that apartment because you have it. I think, too, that part of what’s true for three of the siblings in this story is just that sense that, when you live in New York — if you figure out a way to live in New York, it feels like such an accomplishment. It’s such a hard place to live and especially decide to have your kids and have a family. And when you figure it out, the thought of losing it, the thought of letting go of it seems like such a failure, and you make compromises and decisions that maybe you shouldn’t just to stay where you are. Because losing ground in New York . . . it really hurts.

SO: When I think of my office, it is just piled with notes, with research, with materials. So I pictured you sitting at a very tidy desk, having your imaginary friends in your head kind of directing the story. But it sounds like at least you had Post-It notes.

CS: I had a huge bulletin board. I like to see things, the chapters plotted out. Also I was juggling these characters, and I was juggling the Plumb family, and I was juggling peripheral characters, so they had two different-color Post-It notes. I was keeping track — if I saw, “Oh, I have too many blue chapters in a row; I need to get a pink one in there.” Then I had an index. It was a mess.

SO: Were there any major characters or major tropes in the book that you ended up cutting out?

CS: When I started the book, I was in an MFA program, and I knew that one of the characters was going to be a writer, and I just thought, “I cannot make her a fiction writer; that is not something that you are supposed to do; it is a no-no; you are not supposed to show up in workshop with a novel with a character who can’t write a novel.” When someone does, you can just feel the entire room go, “Oh . . . ” So I somehow thought it would be a good idea to make her a poet. And she was a poet throughout the entire first draft.

SO: Oh, really.

CS: My thesis advisor and now friend — no-bullshit friend — read the first draft, and kind of while he was reading things, he was, like, “The point being . . . Are the stakes really that high for her for poetry?” But we came up with some ideas. He was like, “OK, maybe if you do this and maybe if you do that.” He read the first draft, and he just said, “It’s not working; she has to write something else.” I landed on the idea of her having been a short story writer and having written these stories about her brother Leo, and had become successful very young and then lost her touch. As soon as I made that decision, I was really excited about it, and as soon as I started writing Bea as a fiction writer, literally the entire book came up, and everything came together, and it solved all kinds of little connectivity problems. They are among my favorite chapters, and they were the most fun to write.

So I have to remind myself that really the only time in this process that I made a decision based on worrying about selling the book, it was the wrong decision.

SO: This will sound like a funny question. But did you do what you set out to do with the book? Did you feel when you were done that it had achieved what you were hoping for?

CS: Yes. I think I wrote the book that I wanted to write. Someone asked me last night if I felt like, “Oh, this is it; I love it; it’s perfect.” And I don’t. I feel like it’s the best version of this book I could write when I wrote it, and I’m proud of it, but even when I’ve been reading over the past few nights, all my pages are marked up.

SO: Did you edit a lot? I mean, you mentioned the first draft, and I know you worked through this quite a bit. How much of an editor are you of your own work? Do you throw stuff out?

CS: I throw so much stuff out. I worked as a nonfiction writer for many-many-many years, and I was writing stuff that wasn’t mine, that I didn’t have ownership of, and so I became very accustomed to kind of detaching from it. So yes, I threw out tons of stuff. I think I am a really good editor, and I went through the manuscript many-many-many times before I started clearing agents, or before it went out to publishers. I’m pretty anal about editing.

SO: This is maybe partly speculative. But what do you feel has connected for a reader? What part of it did you write imagining how it would feel being read, and what has been your experience now that you’re out in the world with how people are responding? It’s interesting that you say it’s a book about family, not a book about money, and yet some people may read it . . .

CS: Yes, I may be the only person who thinks that way!

SO: I remember once writing something that I thought was really depressing, and having someone say, “I just finished your piece; it was so fun.” I thought, “Wow!” The fact is, this is out in the world now. People will respond to it on their own. But what’s that been like for you, and what have you found that’s surprised you?

CS: That everyone wants to talk to me about money and trusts and inheritances, and they want me to tell them whether or not it’s a good idea to leave money to their children.

SO: Oh my God, so this has really turned into a financial literacy book.

CS: Yes. It’s like, Rich Dad, Poor Dad or something. I have no idea. I literally have no advice to give you! In almost every interview someone has said, “So, do you think it’s a good idea or a bad idea for parents to leave money to their children?” That has taken me by surprise.

SO: One thing that’s amazing about a book is that after you’ve birthed it, it really is its own entity, it has its own life. I remember that when I was on my book tour for The Orchid Thief, and I took a question at a reading, and someone said, “I have a Phalaenopsis that doesn’t look good; do you have any . . . ” I thought, “I failed totally if you think, first of all, if you think I know anything about taking care of orchids, but also if that’s what you think this book is about.” But then I thought that’s what reading is, in a way — and that someone should read it is a joy.

CS: I think it’s cool. Six weeks ago, I would have said, “This is a book about family, and that’s why people connect to it.” I can tell you now that people connect to it because it’s about money, and people are fascinated by money.

SO: I am sort of filled with awe about the idea that I created something, but it’s independent of me, and that someone can read it and have a completely individual reaction that I am not even controlling.

CS: Yes. It’s a transaction between the reader and the book that has nothing to do with you, and that’s very cool.

SO: Even if they think it’s about how to invest in a 401(k), it’s OK. It’s just different.

CS: I know. “What’s that thing for college tuition? Do that.”