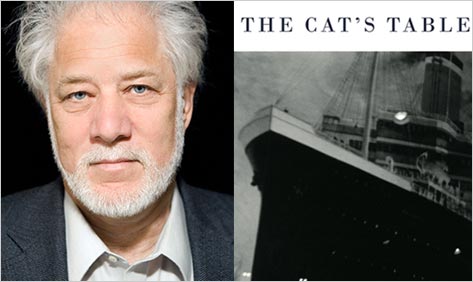

Michael Ondaatje

In the run-up to this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature announcement (an award taken home by the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer), Michael Ondaatje was mentioned as a contender for the prize. When informed of this fact, Ondaatje appeared genuinely humbled, as though he had no business being mentioned in such select company. Indeed, he toiled for years in obscurity, and recalls waiting for, “a review six months later, and it was three lines long and you kind of clutched at that.” He no longer has to wait for reviews, not since The English Patient was awarded the Booker Prize and made into a hugely successful film. His new books since have been greeted as a major literary event, and The Cat’s Table, is no exception [Editor’s Note: Read our review here]. I talked with Ondaatje in October at a New York hotel. An edited transcript of our conversation follows:

The Barnes & Noble Review: In an essay on Leonard Cohen, you once wrote, “Nothing is more irritating than to have your work translated by your life.”

Michael Ondaatje: I was probably about eighteen years old at the time (laughs). Not to be trusted. No, I think he was someone who, very early on, was playing with the whole “persona” thing. I mean, he was “Leonard,” in quotation marks, and at that time in Canada, he was really kind of the only poetry superstar. I guess the problem is that, if that’s the only way of interpreting the work, it’s an irritation. But obviously, in this book, by using that name, I’m stepping into the lion’s mouth.

BNR: But there were a couple of points where you seemed to make a very distinct choice to separate yourself from the narrator. One that stands out is when the narrator says, “I am someone who has a cold heart.” I hate to interpret that through the lens of your life, but to me it wasn’t at all the impression your other work gives of you as a man.

MO: Actually, that would be the moment that clarified for me the distinction between me and him. I think that what’s interesting is what you invent, in that even if it’s fictional, it has many, many grains of yourself, and many grains of alternative selves. And what you pick as an alternative life is in many ways as autobiographical. It’s like painters’ self-portraits. On one level they’re always more sophisticated than they are, or more humble than they are.

BNR: One of the wonderful things in your work is the use of apocryphal stories as characterization. You had a lot of latitude with that in this book, since so many characters on the ship have shadowy backgrounds.

MO: It has to be close to the tone of the character. Of course the boys are happy to believe the fantastic things, and they want to share them, too. I think there’s one line about, “We’d look out at the sea and invent stories for ourselves and for them,” so there’s an element of, “How much of it is their fictions?”

BNR: I loved the inclusion of overheard conversations in the book. It made me think of something Richard Russo wrote about walking, how you move at a different speed and hear what he called “back porch conversations.”

MO: I think I have Cassius watching, Michael is a listener. And I always love listening. The other day I was in Toronto walking down the street and two women cops were cycling, in uniform, and I heard one of them say, “You know those great one-night stands we used to have?” I thought, “Wait! I need to hear the rest.”

BNR: It’s been written that this is a “lighter” book than your others. It brought to mind the line Graham Greene drew between his serious novels and his “entertainments.” But this is not an entertainment.

MO: I don’t think so, no. I must go back and read it — there was an essay by Calvino on “lightness.” I’m not quite sure what he was talking about, as I remember it right now, but I wanted that kind of lightness. When people say lightness, they mean less complicated, usually, and in some ways, I think the structure is as complicated in this book as in any of the other books.

BNR: Can we talk about Kipling? There’s a ghost of him here and elsewhere in your work. It’s clear he means something to you, even though he’s pretty unfashionable these days.

MO: I think one of the problems is that at the beginning of the century you’ve got Kipling and you’ve got Conrad. And they’re kind of heavy-footed to a certain extent. I haven’t read that much of Kipling, but I know Kim was very important to me, and I read it again about fifteen years ago, and I’d probably want to read it again now. And I remember reading that introduction by [Edward] Said, which is fantastic. It’s so loving and so angry at the same time. I love that ambivalence, and admitting that ambivalence. I’m sure that book is very central to me in some way. We have to be more forgiving of our ancestors than “Oh, he said the wrong thing, or used the wrong word.” The great thing is we continually change and evolve.

BNR: I’ve been told Norman Mailer said he was never quite sure how good his work was, because no one would tell him the truth. From the start he was such a success that he was never told no, so to speak. Do you feel lucky that the major recognition came so much later for you?

MO: I was very lucky that way. I think about that, I think of someone like McInerney, who writes that first book, and no one can survive that. It must be a nightmare. I was really lucky that I was with small presses for so long. You’d expect a review six months later, and it was three lines long and you kind of clutched at that. So you weren’t being watched, which was a great thing.

BNR: Yeah, except you’re not being watched.

MO: You don’t want to be watched all your life. You can be watched some of your life. I think connected with that is the whole idea of editing. Though Mailer, I’m sure he was smart enough to take advice, but I think it’s very difficult for publishers to tell their best-selling author, “Lee Child, you’ve got to do something else,” (laughs) but for me, I’m obsessed with not being told what’s wrong, so I usually ask three or four friends, then I work with an editor.

BNR: I look at Mailer, and some of his work is remarkable. But some of it clearly isn’t.

MO: I think Mailer was a great writer. He’s very important to me. Of all the American writers at that time, when I was twenty years old, twenty-five years old, he was the one I was kind of dazzled by because of all the voices and the openness, and the incredible range of perceptions. And not just one point of view about something. All the nonfiction, especially, I like those books more, in a way. If I were Mailer’s publisher I’d have said, “No more Marilyn Monroe. No more CIA. No more Hitler, no more Jesus Christ (laughs).”

BNR: Do you think people would make a natural connection between you and Mailer?

MO: I wouldn’t think so. I’m probably drawn to people like Salter or William Maxwell. I mean, I don’t write like them, William Maxwell I certainly couldn’t write like, I’m stunned by his work. But Mailer, I would hate to put him in just one school.

BNR: Finally, I understand you were happy with Tomas Tranströmer winning the Nobel Prize.

MO: Thrilled. But I was surprised because I thought they wouldn’t give it to a Swede. I thought Adonis was going to get it, actually, but this was good. It appalls me that, if Roth would have gotten it, the papers would have been loaded with news about it. Instead it’s like, “Who is this guy?”

BNR: Listen, this has been a pleasure. Thank you for sitting down with me.

MO: No, thank you. I enjoyed it.