Moïra Fowley-Doyle on Fairytale Themes in The Accident Season

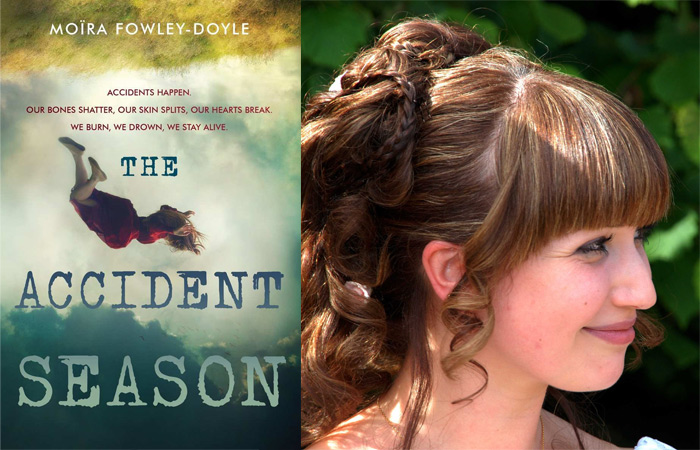

Moïra Fowley-Doyle’s debut, The Accident Season, is a magical-realistic love story that leaves a mark. Cara is the daughter of a family afflicted every October by the “accident season,” when they’re dogged by disasters ranging from scrapes to death. In the waning days of this year’s season, she starts noticing dark omens: a mysteriously missing classmate who shows up in the background of all her photos, a malevolent man who looks like her long-gone stepfather following her through town. The brewing weirdness—and her need for a distraction from her feelings for her ex-stepbrother—inspire Cara to take a huge risk, spending the last day of the accident season throwing a wild Halloween party in an abandoned house on the edge of town. It’s an unsettling book that tackles darkly realistic themes, but there’s enchantment running through the weave. Here’s Fowley-Doyle on the fairytale influences she drew on while writing.

Moïra Fowley-Doyle’s debut, The Accident Season, is a magical-realistic love story that leaves a mark. Cara is the daughter of a family afflicted every October by the “accident season,” when they’re dogged by disasters ranging from scrapes to death. In the waning days of this year’s season, she starts noticing dark omens: a mysteriously missing classmate who shows up in the background of all her photos, a malevolent man who looks like her long-gone stepfather following her through town. The brewing weirdness—and her need for a distraction from her feelings for her ex-stepbrother—inspire Cara to take a huge risk, spending the last day of the accident season throwing a wild Halloween party in an abandoned house on the edge of town. It’s an unsettling book that tackles darkly realistic themes, but there’s enchantment running through the weave. Here’s Fowley-Doyle on the fairytale influences she drew on while writing.

When I write I don’t do a lot of plotting or planning. I wrote the first draft of The Accident Season in a month and a half, which didn’t leave a lot of time for research—with exceptions made for questions like How do you die of hypothermia? and Resetting a dislocated shoulder (with pictures)—but a lot of fairytale themes and fantasy tropes worked their way into the book almost by magic.

The Accident Season

The Accident Season

Hardcover $17.99

The concept of the accident season itself isn’t something I planned in advance. I wanted to write magic realism. I wanted to write about secrets. I wanted to write about a strange girl who set mousetraps and hung flypaper around the forest. I sat down to write that and the first words that came out were: It’s the accident season, the same time every year. And while that was in part influenced by the fact that I’m ridiculously accident-prone, and in part that I did a fair amount of stupid stuff as a teenager, a lot of the themes in The Accident Season were influenced by fairytales and folktales, by woods and rivers, by the waters and the wild.

In the beginning of The Accident Season, Cara sees a group of changeling siblings dressed for a masquerade ball in the watery reflection of her and her friends in a train window. I’ve been fascinated with the idea of changelings since reading Maurice Sendak’s Outside Over There and W.B. Yeats’s collections of Irish fairy tales as a child. Whether the changeling siblings Cara sees in The Accident Season are real or just a figment of her imagination, they fill the very fay purpose of reflecting a better or truer version of the real world to her. She looks to the changelings instead of facing her reality, because, like in Yeats’s poem, the world’s more full of weeping than she can understand.

Inspired by the sight of these changelings who then shadow her through her dreams, Cara and her witchy best friend, Bea, her ex-stepbrother, Sam, and her troubled sister, Alice, decide to throw a masked Halloween party (“The Black Cat and Whiskey Moon Masquerade Ball”) in an abandoned house outside of town. The invitations tell people to wear the costume that best expresses their true self: the changeling behind the human mask. The concept of Halloween masks for hiding is an ancient one, and I liked the topsy-turvy logic of a mask revealing your true self.

The costumes that Cara and her friends find—costumes that mirror the changelings in the train window—are mostly taken from fairly straight-forward mythology: a fairy for Cara, a mermaid for Bea, the big bad wolf for Nick. Alice’s costume is based on Daphne from Greek mythology: a woman who turned into a tree to escape the advances of the god Apollo. (The inspiration for Sam’s costume, on the other hand, came from the Weetzie Bat books by Francesca Lia Block, and is a veiled homage to Charlie Bat, the flickering silent-film ghostguy.)

The changeling siblings show up to the party—or maybe it’s just been in Cara’s head all along—followed by their evil stepfather. He is a metal man because iron is poison to fairies. There is, however—or there once was—an actual human statue street performer in Galway dressed all in metal with gunpowder-grey skin, although I’m sure he is not secretly an evil stepfather in disguise.

A lot of what influenced the fairytale themes in The Accident Season was woods and wolves and rivers. What Bea tells the others in the ghost house before the party is true (especially the part about wolves taking human form): before the seventeenth century, Ireland was mostly forest and was densely populated by wolves. Throughout the 1600s land-owners employed professional wolf hunters to thin the population. They were paid per skin they returned. Nowadays there are no wolves in Ireland but they are an important part of our collective consciousness.

A lot of these fairytale themes come from the landscape. The Accident Season is set in a mostly fictional small town in Co Mayo. Haunted houses are everywhere in fiction—every decent scary story should have one. But The Accident Season isn’t horror, and the ghost house isn’t necessarily haunted. Abandoned once-thatched cottages, collapsing manor houses, the ruins of old churches and crumbling castles are scattered all over rural Ireland. It’s impossible not to see them and wonder about what happened inside.

So this book was quietly influenced by fairytales and folktales, by the everyday magic of the west of Ireland, by the waters and the wild, and things that aren’t quite what they seem.

The Accident Season is available now.

The concept of the accident season itself isn’t something I planned in advance. I wanted to write magic realism. I wanted to write about secrets. I wanted to write about a strange girl who set mousetraps and hung flypaper around the forest. I sat down to write that and the first words that came out were: It’s the accident season, the same time every year. And while that was in part influenced by the fact that I’m ridiculously accident-prone, and in part that I did a fair amount of stupid stuff as a teenager, a lot of the themes in The Accident Season were influenced by fairytales and folktales, by woods and rivers, by the waters and the wild.

In the beginning of The Accident Season, Cara sees a group of changeling siblings dressed for a masquerade ball in the watery reflection of her and her friends in a train window. I’ve been fascinated with the idea of changelings since reading Maurice Sendak’s Outside Over There and W.B. Yeats’s collections of Irish fairy tales as a child. Whether the changeling siblings Cara sees in The Accident Season are real or just a figment of her imagination, they fill the very fay purpose of reflecting a better or truer version of the real world to her. She looks to the changelings instead of facing her reality, because, like in Yeats’s poem, the world’s more full of weeping than she can understand.

Inspired by the sight of these changelings who then shadow her through her dreams, Cara and her witchy best friend, Bea, her ex-stepbrother, Sam, and her troubled sister, Alice, decide to throw a masked Halloween party (“The Black Cat and Whiskey Moon Masquerade Ball”) in an abandoned house outside of town. The invitations tell people to wear the costume that best expresses their true self: the changeling behind the human mask. The concept of Halloween masks for hiding is an ancient one, and I liked the topsy-turvy logic of a mask revealing your true self.

The costumes that Cara and her friends find—costumes that mirror the changelings in the train window—are mostly taken from fairly straight-forward mythology: a fairy for Cara, a mermaid for Bea, the big bad wolf for Nick. Alice’s costume is based on Daphne from Greek mythology: a woman who turned into a tree to escape the advances of the god Apollo. (The inspiration for Sam’s costume, on the other hand, came from the Weetzie Bat books by Francesca Lia Block, and is a veiled homage to Charlie Bat, the flickering silent-film ghostguy.)

The changeling siblings show up to the party—or maybe it’s just been in Cara’s head all along—followed by their evil stepfather. He is a metal man because iron is poison to fairies. There is, however—or there once was—an actual human statue street performer in Galway dressed all in metal with gunpowder-grey skin, although I’m sure he is not secretly an evil stepfather in disguise.

A lot of what influenced the fairytale themes in The Accident Season was woods and wolves and rivers. What Bea tells the others in the ghost house before the party is true (especially the part about wolves taking human form): before the seventeenth century, Ireland was mostly forest and was densely populated by wolves. Throughout the 1600s land-owners employed professional wolf hunters to thin the population. They were paid per skin they returned. Nowadays there are no wolves in Ireland but they are an important part of our collective consciousness.

A lot of these fairytale themes come from the landscape. The Accident Season is set in a mostly fictional small town in Co Mayo. Haunted houses are everywhere in fiction—every decent scary story should have one. But The Accident Season isn’t horror, and the ghost house isn’t necessarily haunted. Abandoned once-thatched cottages, collapsing manor houses, the ruins of old churches and crumbling castles are scattered all over rural Ireland. It’s impossible not to see them and wonder about what happened inside.

So this book was quietly influenced by fairytales and folktales, by the everyday magic of the west of Ireland, by the waters and the wild, and things that aren’t quite what they seem.

The Accident Season is available now.