“Strange Things Happen at Wolf Hall:” 14 Things We Learned At Hilary Mantel’s #BNAuthorEvent

Hilary Mantel is the author of the wildly popular Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, two books that focus on Thomas Cromwell and the Tudors, and have been turned into a hit TV show and plays in both London and the US. With Mike Poulton, she wrote Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies: The Stage Adaptation, on sale now, and she spoke before an audience in New York City about watching her characters come alive on stage and screen.

She’s aware how dark and difficult her books are. “Being so close to this material, I probably forget how disturbing it is. How far off from the kind of redemptive narrative that tends to carry away awards. We make our audience feel but it isn’t feel-good. It’s dark. It’s difficult. The kind of narrative that is easy to like and easy to judge and easy to reward is the kind of narrative where they are lying in the gutter but are looking at the stars. And it’s about self-realization it’s about triumph agains the odds. It’s against smiling through your tears. But in our plays and in my books if you’re lying in the gutter you’re lying in the dirt. You’re not smiling through your tears, youre spitting out your teeth. It’s harsh it’s violent. But it’s Tudor life, we get on with it.”

She didn’t plan to write three books about Cromwell. “When I first wrote Wolf Hall, I thought I could tell the whole of Thomas Cromwell’s story in in one book. That was my plan. It was only when I got part way through that I came to realize the complexity of the material.”

Mike Poulton was a great teammate. “We worked together and we worked productively, usually in different parts of the country, sitting up all night, emailing each other draft after draft, scene after scene. I think we entered some sort of match or contest, who could be at the word processor the latest, and who could get up the earliest. I think Mike won because I don’t think he ever slept. And the plays had these amazing disposition to grow longer and longer. In those scant hours when I was asleep and Mike was doing whatever Mike was doing, I think the characters rose from the dead sat down at the keyboard and tapped out more parts. It’s the only explanation I can come up with for why we went to Stratford-on-Avon (where the play is being produced) with plays that were at least a half an hour too long.”

Wolf Hall

Wolf Hall

Paperback $16.00

Finding the perfect characters for the play was all about their energies, not their looks. “When they cast they weren’t after look-a-likes. We wanted someone who could embody the energy of the characters. Because that’s how they are in my mind. Each one was a distinctive energy. And it was much more important to capture that than to match them up feature for features.”

Writing the play helped her write the third book. “The process of the rehearsal would give me insight as to what I should do, how I might develop characters, even going onto the third book. You might say by the end of the second book, the second play, “isn’t everyone mostly dead?’ This doesn’t stop character development. How can they develop or evolve? Because they go on in Thomas Cromwell’s mind and in memory, that’s where history changes. The dead change long after they’re buried.”

The third book is taking its time to be written. “People ask me when the third book will be done and I say, “when it wants to be.” This is a big project in my life. I don’t want to compromise it. I owe it to too many lovely readers, a respective audience, to get it right. And if that means taking another season so be it.”

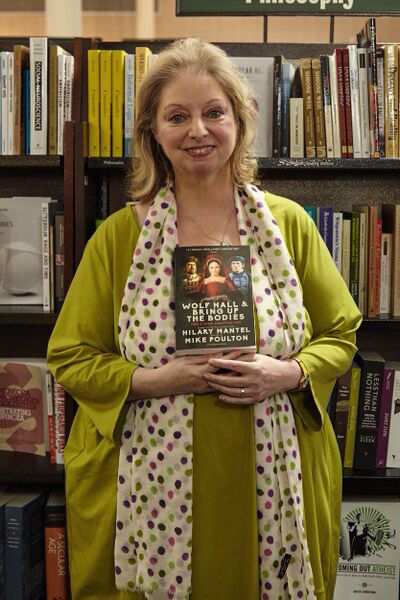

[caption id="attachment_28163" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Photography by Andrew Katzowitz[/caption]

Stage production changed greatly when Mantel and Poulton brought the play to the US. “It wasn’t a question of translating it for an American audience as people sometimes think. I have always found that my American readers are as well informed as my English readers. And I anticipated, and thankfully I was right, that Broadway audiences would be very quick. When we were asked was to shorten the scripts, that meant big restructuring, big rewriting and it gave me the chance to put into play some new ideas to consider from the actors and what they brought to it and allowed me to profit from the experience and their commitment to the characters. The actors give me so many ideas often unconsciously. They’re quite capable of turning around to me and saying, “I would never do that,” I like that. Because it means they’re thinking inside that person.”

[caption id="attachment_28164" align="alignright" width="400"] Photography by Andrew Katzowitz[/caption]

She is enjoying the ride. “This is a central part of my life but it is also the most interesting creatively. I never imagined for myself the creative gains of the last two years, the way it may change what I do in the future, the ideas that have poured in, simply the amount I have learned, I would say more about writing in the last two years than in the previous ten. And I never imagined the success—the phenomenon—that the books have become. So many people have poured their talent and their commitment into them. I never imagined it but then as one of the characters said, “Strange things happen at Wolf Hall.”

Her high school history teacher inspired her to fall in love with historical fiction. (But not as you’d think.) “It’s a very great challenge to write historical fiction. You can always tell who’s done their research and who hasn’t. What goes on the page has got to be the tip of the ice berg and supported from below by all the other things you learned. I think I learned this from my history teacher in high school. When we think of inspirational teachers we think of wonderful stories and making the past dramatic. She didn’t do that. She just stood eloquently and we took notes as best we could. But why she was intriguing and led me on into the study of history was that you knew that there was much more to it than she was telling you. It’s a great lure that you know that there is a greater complexity waiting. And having learned that from her that has always been the way I’ve tried to work—from the great mass of facts you have you must select the right one, the telling detail, the one that makes a page sing. Don’t tell the reader all you know just to make the reader want to know more.”

Writing for theater has made her a better writer in general. “I’ve enjoyed facing new challenges in storytelling, which is always good for a writer part when yo’ve come to a certain part in your career when frankly you could just get by doing just what you did. But you don’t want to get into that groove. I’ve had the invaluable experience of being a beginner, walking into the rehearsal room thinking, “I have no idea what’s going on.” It’s so valuable to be plunged back into that creative chaos. There are things I’ve learned about the characters and storylines that I would not have invented if I hadn’t been working with the actors.”

Finding the perfect characters for the play was all about their energies, not their looks. “When they cast they weren’t after look-a-likes. We wanted someone who could embody the energy of the characters. Because that’s how they are in my mind. Each one was a distinctive energy. And it was much more important to capture that than to match them up feature for features.”

Writing the play helped her write the third book. “The process of the rehearsal would give me insight as to what I should do, how I might develop characters, even going onto the third book. You might say by the end of the second book, the second play, “isn’t everyone mostly dead?’ This doesn’t stop character development. How can they develop or evolve? Because they go on in Thomas Cromwell’s mind and in memory, that’s where history changes. The dead change long after they’re buried.”

The third book is taking its time to be written. “People ask me when the third book will be done and I say, “when it wants to be.” This is a big project in my life. I don’t want to compromise it. I owe it to too many lovely readers, a respective audience, to get it right. And if that means taking another season so be it.”

[caption id="attachment_28163" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Photography by Andrew Katzowitz[/caption]

Stage production changed greatly when Mantel and Poulton brought the play to the US. “It wasn’t a question of translating it for an American audience as people sometimes think. I have always found that my American readers are as well informed as my English readers. And I anticipated, and thankfully I was right, that Broadway audiences would be very quick. When we were asked was to shorten the scripts, that meant big restructuring, big rewriting and it gave me the chance to put into play some new ideas to consider from the actors and what they brought to it and allowed me to profit from the experience and their commitment to the characters. The actors give me so many ideas often unconsciously. They’re quite capable of turning around to me and saying, “I would never do that,” I like that. Because it means they’re thinking inside that person.”

[caption id="attachment_28164" align="alignright" width="400"] Photography by Andrew Katzowitz[/caption]

She is enjoying the ride. “This is a central part of my life but it is also the most interesting creatively. I never imagined for myself the creative gains of the last two years, the way it may change what I do in the future, the ideas that have poured in, simply the amount I have learned, I would say more about writing in the last two years than in the previous ten. And I never imagined the success—the phenomenon—that the books have become. So many people have poured their talent and their commitment into them. I never imagined it but then as one of the characters said, “Strange things happen at Wolf Hall.”

Her high school history teacher inspired her to fall in love with historical fiction. (But not as you’d think.) “It’s a very great challenge to write historical fiction. You can always tell who’s done their research and who hasn’t. What goes on the page has got to be the tip of the ice berg and supported from below by all the other things you learned. I think I learned this from my history teacher in high school. When we think of inspirational teachers we think of wonderful stories and making the past dramatic. She didn’t do that. She just stood eloquently and we took notes as best we could. But why she was intriguing and led me on into the study of history was that you knew that there was much more to it than she was telling you. It’s a great lure that you know that there is a greater complexity waiting. And having learned that from her that has always been the way I’ve tried to work—from the great mass of facts you have you must select the right one, the telling detail, the one that makes a page sing. Don’t tell the reader all you know just to make the reader want to know more.”

Writing for theater has made her a better writer in general. “I’ve enjoyed facing new challenges in storytelling, which is always good for a writer part when yo’ve come to a certain part in your career when frankly you could just get by doing just what you did. But you don’t want to get into that groove. I’ve had the invaluable experience of being a beginner, walking into the rehearsal room thinking, “I have no idea what’s going on.” It’s so valuable to be plunged back into that creative chaos. There are things I’ve learned about the characters and storylines that I would not have invented if I hadn’t been working with the actors.”

Bring Up the Bodies: The Conclusion to PBS Masterpiece's Wolf Hall: A Novel

Bring Up the Bodies: The Conclusion to PBS Masterpiece's Wolf Hall: A Novel

Paperback $16.00

For Mantel, history comes alive in her research. “In the early days of the play, the week before we went into preview, I was going back to my hotel room reading Thomas Wyatt’s poem written after the death of Anne Boleyn about the lovers, the men who died with her. A verse for each one. It’s an awe-inspiriting and shaking poem. Wyatt has watched these men go to their death. We know where he was held. I read his verse around again and again and again and suddenly I think, “Oh my god he thinks Henry Norris is guilty!” And I can’t prove that. It came flying to me as an instinct. And I read it again and again and again and convinced myself I was right. But that portion of that book is already done. There’s always flashback.”

Some of the parts of the play are not in the book. “There were reasons I didn’t feel comfortable writing Thomas More’s trial into my novel but everyone said, “Come on, Hill. People expect the trial.” And they do. So I put some stuff together and I was happy with the way it turned out.”

For Mantel, history comes alive in her research. “In the early days of the play, the week before we went into preview, I was going back to my hotel room reading Thomas Wyatt’s poem written after the death of Anne Boleyn about the lovers, the men who died with her. A verse for each one. It’s an awe-inspiriting and shaking poem. Wyatt has watched these men go to their death. We know where he was held. I read his verse around again and again and again and suddenly I think, “Oh my god he thinks Henry Norris is guilty!” And I can’t prove that. It came flying to me as an instinct. And I read it again and again and again and convinced myself I was right. But that portion of that book is already done. There’s always flashback.”

Some of the parts of the play are not in the book. “There were reasons I didn’t feel comfortable writing Thomas More’s trial into my novel but everyone said, “Come on, Hill. People expect the trial.” And they do. So I put some stuff together and I was happy with the way it turned out.”

Wolf Hall & Bring Up the Bodies: The Stage Adaptation

Wolf Hall & Bring Up the Bodies: The Stage Adaptation

By

Hilary Mantel

Adapted by

Mike Poulton

Paperback $16.00

Mantel cares about details. “In the play, people carry about all sorts of letters and piles of papers, and if by chance they were to drop one one night the audience would see that what’s inside is just what it should be. There’s a brillaitnt woman in Stratford-on-Avon who sits in a workshop at a big table and impersonates people’s handwriting. When I dropped into see her she was learning the script of William Tyndale so Thomas could have a letter from William Tyndale on his desk. It’s that degree of perfectionism, it isn’t seen by audience but it gives the actors a solid place to stand.”

In Wolf Hall, constantly referring to Cromwell without the antecedent, instead using “he,” was no accident. “I was trying to be always inside his head. I know some readers complained about it, but some readers caught on in the first sentence. It’s always a question when writing historical fiction: how do you feed information to your reader? Two errors: one is to baffle them one is to spoon feed them. If I have to fall into one error or the other I prefer to baffle them. I’ve always wanted to write the book I want to read. I took a risk there and something interesting happens. When you’re inside Cromwell’s head, it seemed to me slightly false that he should be talking about himself, naming himself as Thomas Cromwell, so it became “he.” But as times goes on and the second book dawns, Cromwell is becoming a phenomenon that astonishes even himself. And so sometimes he does name himself he says “he, Cromwell” as if in astonishment that he’s got to be where he is with the people he’s with. I’m trying to do something very difficult with Thomas Cromwell. I’m writing from the inside of the head from a man who is not introspective. He doesn’t take a break to add himself up. He is what he says. People sometimes says “it’s such a deep psychological probing,” but actually it’s not. It’s all illustrated, it’s shown to you. which is why it could take on a visual form.”

[caption id="attachment_28165" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Photography by Andrew Katzowitz[/caption]

Mantel cares about details. “In the play, people carry about all sorts of letters and piles of papers, and if by chance they were to drop one one night the audience would see that what’s inside is just what it should be. There’s a brillaitnt woman in Stratford-on-Avon who sits in a workshop at a big table and impersonates people’s handwriting. When I dropped into see her she was learning the script of William Tyndale so Thomas could have a letter from William Tyndale on his desk. It’s that degree of perfectionism, it isn’t seen by audience but it gives the actors a solid place to stand.”

In Wolf Hall, constantly referring to Cromwell without the antecedent, instead using “he,” was no accident. “I was trying to be always inside his head. I know some readers complained about it, but some readers caught on in the first sentence. It’s always a question when writing historical fiction: how do you feed information to your reader? Two errors: one is to baffle them one is to spoon feed them. If I have to fall into one error or the other I prefer to baffle them. I’ve always wanted to write the book I want to read. I took a risk there and something interesting happens. When you’re inside Cromwell’s head, it seemed to me slightly false that he should be talking about himself, naming himself as Thomas Cromwell, so it became “he.” But as times goes on and the second book dawns, Cromwell is becoming a phenomenon that astonishes even himself. And so sometimes he does name himself he says “he, Cromwell” as if in astonishment that he’s got to be where he is with the people he’s with. I’m trying to do something very difficult with Thomas Cromwell. I’m writing from the inside of the head from a man who is not introspective. He doesn’t take a break to add himself up. He is what he says. People sometimes says “it’s such a deep psychological probing,” but actually it’s not. It’s all illustrated, it’s shown to you. which is why it could take on a visual form.”

[caption id="attachment_28165" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Photography by Andrew Katzowitz[/caption]