A Complex Heroine Navigates a Man’s World in Frances Hardinge’s The Lie Tree

Welcome to the B&N Teen Blog’s feminist YA book club! In this semi-monthly series we’ll be highlighting kickass new and forthcoming YA books with a strong feminist bent. This month we’re discussing Frances Hardinge’s fantastical historical tale The Lie Tree.

“She felt a lurking fear the bridge of science might fail her and come to an uncanny halt, leaving only a drop to dark and secret waters…”

The Lie Tree

The Lie Tree

Hardcover $17.95

In the latest from Frances Hardinge, whose dark fairy tales have a fiery, feminist heart, the 14-year-old daughter of a pastor and disgraced naturalist travels with her family from London to a dingy, clannish island, fleeing encroaching scandal. She has a wilted, flirtatious mother, a father who tells them nothing, a bluff, secretive uncle, and a little brother who becomes her de facto charge. And the girl herself, Faith Sunderly, is mistaken by all of them to be exactly what she appears: a dull and helpless young lady, too boring to possess an inner life, and too dowdy to be noticed.

But Faith is a woman of science, who longs to dodge marriage and follow in her father’s footsteps. On the island, her resolve to be “good”—that is, docile, ladylike, and fearful of the outside world—is tested. Faith peeks at her father’s papers, listens at doors, and tries to make sense of her new world in the absence of information. Among her discoveries: her father, Erasmus Sunderly, has done something bad enough to hit the newspapers. Her uncle has arranged for the formerly celebrated naturalist to join a dig on the island, far, far away from the scandal. And, of course, the scandal has followed them.

Against a background of encroaching disaster, Faith’s father’s behavior grows increasingly erratic, until the night she helps him hide a mysterious botanical specimen in a sea cave. The next morning, he’s found dead, his body broken beneath a cliff on their property. Faith’s mother suspects suicide, but Faith plunges deeper into the mystery, coming to believe it’s foul play. As the villagers close ranks against them, refusing even to bury Erasmus’s body on hallowed ground, and her mother plots to salvage her status one flirtation at a time, Faith seizes her power. She uses the things people would use against her—her ability to go unnoticed, the assumption by adults (men in particular) that she’s docile and stupid—and hones them into weapons.

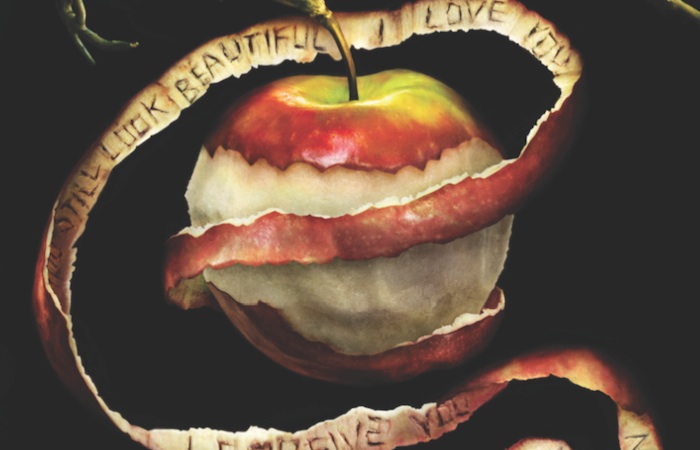

First, she discovers among her father’s papers the nature of what’s hidden in the sea cave, the thing at the root of his destroyed career: a Lie Tree. It’s a plant that flourishes in the dark and is fed, literally, by whispered lies. If you feed the tree a lie, it will produce for you a fruit. The bigger the lie and the more people who believe it, the more potent the fruit. Eating it gifts the liar with impossible knowledge, based on the content of the lie.

With the help of her Lie Tree, Faith builds an intricate web of untruths and feeds them, spreading discord throughout the island. Relying on her intelligence and her cold reading of the smallness of human nature, Faith blooms darkly into a puppet master, destroying peace and relationships with a few well-chosen words, a forged document, a cunning display of feigned foolishness. And soon she learns how a lie can grow, from a flame in your hands to a brushfire that threatens to overtake you.

She’s hungry and dangerous in the way that any big, bright thing stuffed into a box will be, when finally freed. But even as she longs to escape the limitations of her time and gender, she has nevertheless internalized her society’s expectations: she’s brave enough to take late-night boat trips alone in pursuit of her father’s killer, but an unchaperoned conversation with a local boy makes her feel “scalded, sick and unclean.” Hardinge has created a feminist heroine without a whiff of anachronism, whose victories over men and other’s expectations are deeply complex. She’s not courageous in a clean, triumphant way. Her bravery is furtive—sometimes she’s ashamed of what it makes her do. It comes from a place of rage and disappointment with the world; she veers between heedlessness and shame. But always, ultimately, she does what needs to be done.

Thrillingly, Faith’s character arc includes an expansion of her understanding of what female strength can look like. Her mother possesses different, more conventionally feminine tools—a pretty face, a willingness to be subservient—but she wields them just as ruthlessly as Faith does her intelligence and disgust. Even if Faith hates her mother’s methods, she learns with regret to respect their effectiveness, and the reality of their place in the world. Hardinge is never so lazy as to denigrate traditional feminine qualities, but is instead full of a deep compassion for even her smallest female characters, all of whom are trying to keep their footing in a man’s world.

And in a brilliant rebuttal to the clichéd heroine who’s “not like other girls,” she has this to say: “Faith had always told herself that she was not like other ladies. But neither, it seemed, were other ladies.”

The Lie Tree hits shelves April 19, and is available for pre-order now.

In the latest from Frances Hardinge, whose dark fairy tales have a fiery, feminist heart, the 14-year-old daughter of a pastor and disgraced naturalist travels with her family from London to a dingy, clannish island, fleeing encroaching scandal. She has a wilted, flirtatious mother, a father who tells them nothing, a bluff, secretive uncle, and a little brother who becomes her de facto charge. And the girl herself, Faith Sunderly, is mistaken by all of them to be exactly what she appears: a dull and helpless young lady, too boring to possess an inner life, and too dowdy to be noticed.

But Faith is a woman of science, who longs to dodge marriage and follow in her father’s footsteps. On the island, her resolve to be “good”—that is, docile, ladylike, and fearful of the outside world—is tested. Faith peeks at her father’s papers, listens at doors, and tries to make sense of her new world in the absence of information. Among her discoveries: her father, Erasmus Sunderly, has done something bad enough to hit the newspapers. Her uncle has arranged for the formerly celebrated naturalist to join a dig on the island, far, far away from the scandal. And, of course, the scandal has followed them.

Against a background of encroaching disaster, Faith’s father’s behavior grows increasingly erratic, until the night she helps him hide a mysterious botanical specimen in a sea cave. The next morning, he’s found dead, his body broken beneath a cliff on their property. Faith’s mother suspects suicide, but Faith plunges deeper into the mystery, coming to believe it’s foul play. As the villagers close ranks against them, refusing even to bury Erasmus’s body on hallowed ground, and her mother plots to salvage her status one flirtation at a time, Faith seizes her power. She uses the things people would use against her—her ability to go unnoticed, the assumption by adults (men in particular) that she’s docile and stupid—and hones them into weapons.

First, she discovers among her father’s papers the nature of what’s hidden in the sea cave, the thing at the root of his destroyed career: a Lie Tree. It’s a plant that flourishes in the dark and is fed, literally, by whispered lies. If you feed the tree a lie, it will produce for you a fruit. The bigger the lie and the more people who believe it, the more potent the fruit. Eating it gifts the liar with impossible knowledge, based on the content of the lie.

With the help of her Lie Tree, Faith builds an intricate web of untruths and feeds them, spreading discord throughout the island. Relying on her intelligence and her cold reading of the smallness of human nature, Faith blooms darkly into a puppet master, destroying peace and relationships with a few well-chosen words, a forged document, a cunning display of feigned foolishness. And soon she learns how a lie can grow, from a flame in your hands to a brushfire that threatens to overtake you.

She’s hungry and dangerous in the way that any big, bright thing stuffed into a box will be, when finally freed. But even as she longs to escape the limitations of her time and gender, she has nevertheless internalized her society’s expectations: she’s brave enough to take late-night boat trips alone in pursuit of her father’s killer, but an unchaperoned conversation with a local boy makes her feel “scalded, sick and unclean.” Hardinge has created a feminist heroine without a whiff of anachronism, whose victories over men and other’s expectations are deeply complex. She’s not courageous in a clean, triumphant way. Her bravery is furtive—sometimes she’s ashamed of what it makes her do. It comes from a place of rage and disappointment with the world; she veers between heedlessness and shame. But always, ultimately, she does what needs to be done.

Thrillingly, Faith’s character arc includes an expansion of her understanding of what female strength can look like. Her mother possesses different, more conventionally feminine tools—a pretty face, a willingness to be subservient—but she wields them just as ruthlessly as Faith does her intelligence and disgust. Even if Faith hates her mother’s methods, she learns with regret to respect their effectiveness, and the reality of their place in the world. Hardinge is never so lazy as to denigrate traditional feminine qualities, but is instead full of a deep compassion for even her smallest female characters, all of whom are trying to keep their footing in a man’s world.

And in a brilliant rebuttal to the clichéd heroine who’s “not like other girls,” she has this to say: “Faith had always told herself that she was not like other ladies. But neither, it seemed, were other ladies.”

The Lie Tree hits shelves April 19, and is available for pre-order now.