The Magicians Trilogy Will Redefine Your Relationship with Fantasy

Like a lot of kids, there were times in my childhood where I was convinced some grand mistake had been made, and I had been plopped down with the wrong parents, in the wrong world, and that someday, someone far more important and interesting would come along and claim me, so my real adventures could begin. It’s a longing that fuels so much of children’s literature, from Narnia to Oz: that something more exciting is happening just over the rainbow, and you, the chosen child, will be the one to discover it. There’s even a name for it: portal fantasy, the dream that another world exists just beyond the confines of our own, and that great discoveries await us there.

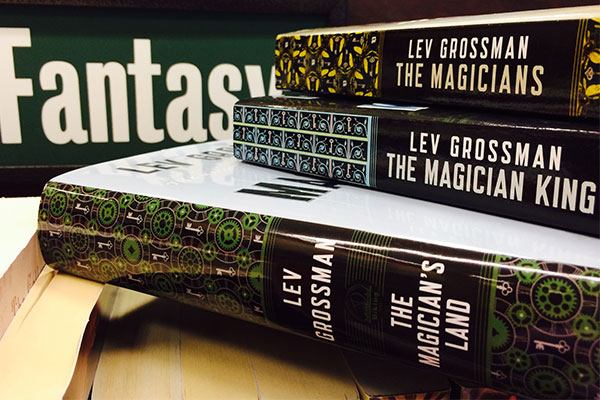

Lev Grossman was definitely that child. The fiction book critic for Time, he has devoted his life to exploring invented worlds, and fantasy has been his passion since his childhood, which was filled with the works of Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Ursula K. LeGuin. But the older he got, the more he couldn’t help but notice that he never did discover that promised door into another world. The back of his wardrobe (a closet, really) remained unfailingly solid and impenetrable. And so he channeled that disappointment into a most unusual fantasy trilogy, a series of books (including The Magicians, The Magician King, and the newly released The Magician’s Land) in which the characters do get to visit a world of wonder and magic, only to discover they can never quite shake off the weight of the mundane lives they’ve left behind.

The first book’s initial buzz was built on the back of its apparent existence as a reaction to the allure of the Harry Potter franchise. Grossman’s proxy is Quentin Coldwater, a spoiled, somewhat insufferable rich kid living in New York City. Like Harry, Quentin has spent his whole life dreaming of being whisked away from his unsatisfying life into a world of fantastical magic, preferably to the land of Fillory, a quasi-Narnian realm full of legendary weapons, questing beasts, and talking bunnies that he grew up reading about in a series of popular (though sadly for us, fictional) books. His real life has fallen so short of the one he feels he deserves, in fact, that he hardly seems surprised when, on the eve of his high school graduation, he is recruited (via the mysterious delivery of a hitherto unknown sixth Fillory book) to take the rigorous entrance exam to attend Brakebills, the Upstate New York version of Hogwarts. Finally, he thinks, I will get what I deserve.

Real life does have a way of falling short of fantasy, however. Quentin quickly discovers that attending a school for magicians is filled with as much tedium as the days he spent in prep school with stuck-up rich kids. Contrary to popular belief, magic isn’t all waving wands and shouting funny words; it’s difficult, and tricky, and intricate, and kind of dull. You’ve probably dreamed of soaring across the Quidditch pitch on a Nimbus 2000, but no one will ever dream of playing Welters, the Brakebills version of a magical sport, which is basically a very slow-paced game of 3-D chess, except not as action-packed. The quirky house competitions of the Potter series are replaced by hormone-fueled backbiting between social cliques; it’s Hogwarts meets The Secret History.

Later on (and here there be spoilers, though I won’t give too much away), Quentin and a few of his Brakebills graduates even figure out a way to travel to Fillory itself. And though Fillory is admittedly pretty great (there’s a gleaming castle that rotates on dwarven gears! A grove of clock trees! All the talking animals you could ever want!), it’s also a far grimmer spot than described in the books, and the Fillorian analogues for the Pevensie children of Narnia didn’t get away clean, either (life makes monsters of us all).

This could all be viewed as deeply cynical. Quentin gets what every kid dreams of, finds out that even casting spells gets pretty boring after a while, and proceeds to Holden Caulfield himself through an experience many would kill for. But like any good fantasy, this trilogy is also about the journey, and Quentin does a lot of growing up over the course of three books. The series only gets better as it goes, as Grossman gets a better handle on his characters and figures out how to fit the Important Points he is making into a highly addictive plot. The Magician King is more ambitious than book one by half, bringing in a new point-of-view character, Julia, one of Quentin’s prep school classmates who didn’t make the cut at Brakebills and had to discover magic the hard (often brutal) way. Julia both embodies and subverts genre tropes, and her deeply troubling, risky storyline reveals Grossman’s commitment to follow his thesis—that we are, ultimately, the sum of the choices we make—to its logical conclusion. By the end of The Magician’s Land, Quentin and his fellow Kings and Queens of Fillory have changed the world, but not without being profoundly changed (and damaged) themselves, and that maturation is something we all must face eventually, even if it usually doesn’t involve a ride on a hippogriff or a standoff with a giant talking turtle.

In the end, any accusations of cynicism seem unfounded. Grossman’s intent goes far beyond letting the air out of our collective modern myths. This isn’t a story about how life is terrible here, there and back again, but how sometimes the answer isn’t finding an escape from your problems, but growing up and figuring out how to deal. And while it takes Quentin most of three books to do that, it took me a lot longer than three books to figure myself out. In fact, I’m pretty sure George R.R. Martin will finish his story before I’ve got a handle on mine.

Have you read The Magicians Trilogy?