Turn of Mind

Anyone with a friend or loved one who has been stricken with Alzheimer’s must be intrigued—darkly fascinated—by what might, or might not, be going on in the atrophying consciousness of the sufferer. What lies behind the often impassive mask that is referred to by doctors as the “lion face”? What are the roots of the countless anxieties that seem to torment the patient? Memory? Association? Why the look of childlike terror that tends to alternate with the blank, leonine stare?

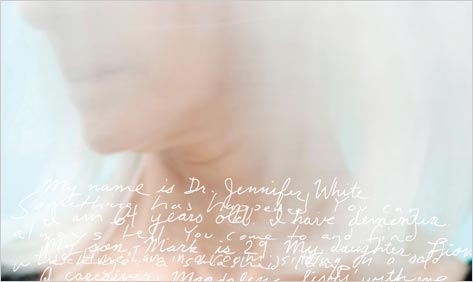

John Bayley’s Elegy for Iris, an account of the mental degeneration of his brilliant wife, Iris Murdoch, provided an unforgettable outsider-looking-in view of the disease. Bayley eloquently projected himself into his spouse’s unknowable psyche. “Most days are, for her,” he wrote, “a sort of despair, although despair suggests a conscious and positive state whereas what she feels is a vacancy that frightens her by its lack of dimension.” Now Alice LaPlante, a California-based writer who has watched her own mother battle Alzheimer’s for over a decade, has attempted a fictional exploration of the illness from the point of view of the patient—an exacting exercise not only of empathy but of literary technique. Traditional stream-of-consciousness fiction is difficult enough, but to attempt it on a consciousness as wandering and fragmented as that of Dr. Jennifer White, the protagonist of LaPlante’s Turn of Mind, is a daunting task. The author has made it all the more difficult by conceiving her novel in the form of a mystery/thriller.

The first page of the book establishes Jennifer’s state of mind. “I am in a room, sitting on a cold metal folding chair. The room is not familiar, but I am used to that. I look for clues…. Men and women talking; to one another, not to me. Some wearing baggy suits, some in jeans. And more uniforms. My guess is that a smile would be inappropriate. Fear might not be.” And later: “Hazards life around every corner. So you nod to all the strangers who force themselves upon you. You laugh when others laugh, look serious when they do. When people ask do you remember you nod some more. Or frown at first, then let your face light up in recognition.”

As an approximation of what such disorientation must feel like, all this seems reasonable enough, and it conveys a genuine feeling for dementia’s malaise: the uncertainty not only about who and where you are, but of what sort of behavior might be appropriate to the situation. But would a woman at this stage of mental deterioration be thinking in sentences at all? Or would her thoughts amount to a random sequence of images and dissociated, even inapplicable words? Difficult to know, though LaPlante’s decision to transcribe Jennifer’s thoughts coherently has made for a readable and comprehensible book, if one that cannot be entirely true to the felt reality of Alzheimer’s.

Before the disease, Jennifer White was a brilliant woman, an orthopedist specializing in delicate hand surgery. Reduced now to near-imbecility, she still displays occasional flashes of her former professional acumen. So when her neighbor and longtime best friend Amanda is found dead, with three fingers expertly severed, Jennifer becomes the most obvious suspect. But did she do it—and if so, why? How can the police extract a confession, if she is indeed guilty? What does she remember—and are the images and vague recollections that flit through her mind genuine at all?

Jennifer’s devices for constructing a view of her new reality are limited, and as the disease progresses they become increasingly unhelpful. Her two adult children and her caregiver, Magdalena, attempt to ground her in the present by talking to Jennifer and writing in a journal to which she can refer for enlightenment. But how can you trust people to whom you constantly have to be reintroduced? Every time Jennifer comes across Magdalena sitting in the kitchen, she is startled by what she thinks is a stranger in her home. And as for the children: “A man has walked into my house without knocking. He says he is my son. Magdalena backs him up, so I acquiesce. But I don’t like this man’s face. I am not ruling out the possibility that they are telling me the truth—but I will play it safe. Not commit.”

It is with the dissociated fragments of Jennifer’s thoughts and memories that we, the readers, slowly construct the backstory to her current state and (perhaps more important) a portrait of the murdered Amanda. For the relationship with the formidable Amanda turns out to have been the defining one of Jennifer’s life, far more than those with her fascinating husband or even her beloved daughter, Fiona. Amanda, who in intelligence and intransigence was the equal or superior of Jennifer herself, and more: “an avenging angel. That is her genius—spotting the carcass before it has begun to rot. She out-vultures the vultures.”

Turn of Mind is an ambitious piece of work, really too ambitious to succeed on all three of the levels LaPlante has set out to master: mystery, psychological novel, experiment in the aesthetic presentation of dementia. As a mystery, Turn of Mind is not particularly interesting; we see the “surprise” ending coming all too soon. As an effort to communicate the sensations of dementia, it is, as I have indicated, successful and certainly thought-provoking: LaPlante expertly communicates not only the patient’s anxieties but the reflected ones of the caregiver as well.

But as psychological novel, Turn of Mind falls somewhat short. LaPlante has meticulously planted thematic links and clues to do with Jennifer’s vestigial Catholicism, her fascination with the human hand, and her fear of physical and spiritual corruption, but we still do not have a complete idea of just what sort of a human being the pre-Alzheimer’s Jennifer was, or of the driving forces behind her relationships with her husband and children. Nor do we ever understand the redoubtable Amanda, whose character, after all, is the key to the entire mystery. At what point did her outsized ego separate from her outsized sense of righteousness? What were the sources of her avenging-angel persona? Jennifer might have understood it all once, but she (and her author) can’t seem to convey the information now, and in the end the reader comes up against a literary version of the impassive “lion face” of Alzheimer’s.