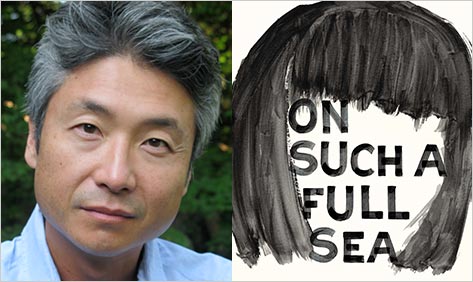

Wave of the Future: Chang-rae Lee

Chang-rae Lee has always been a master at exposing, with immense generosity, the intricacies and contradictions of human psychology. His first three novels are confessionals, narratives of men often taken to be less complex, in some ways less feeling and in others less treacherous, than they actually are. His fourth novel, The Surrendered , is a multi-generational story with three protagonists whose fates are set in motion by the horrors of the Korean War. On Such a Full Sea, his most recent book — and in some ways his most intriguing yet — begins in B-Mor, an impeccably restored and unsettlingly well-ordered future Baltimore, shortly after one of the residents, Fan, has fled the safety of the city for the dangers of the counties. Fan has presumably left in search of her boyfriend, who recently disappeared. The story is told in the first-person plural, by a communal “We,” the narrators being descendants of “New China” immigrants. They cling to their lower-middle-class existence by working rote but exhausting factory jobs and never being the nail that sticks up.

I finished reading the novel while visiting family in New England over Thanksgiving, and the train ride back from Springfield, Mass. to Penn Station, past countless crumbling smokestacks and deserted factories, did nothing to lessen my sense that we are already half-living in this dystopian world he portrays.

In early December, Chang-rae Lee and I met in Manhattan to talk about On Such a Full Sea. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation. — Maud Newton

Maud Newton: I’ve been a fan of your novels for a long time, but this is a really different kind of thing. Chang-rae Lee: Yes. Obviously, I knew it was a very different kind of thing, but I tried not to think about it. The more I thought about it, people asked me what I’m working on and I started talking about it, I’d get kind of scared. [Laughs]

Chang-rae Lee: Yes. Obviously, I knew it was a very different kind of thing, but I tried not to think about it. The more I thought about it, people asked me what I’m working on and I started talking about it, I’d get kind of scared. [Laughs]

MN: It’s both futuristic and contemporary, quasi-apocalyptic yet hopeful about humanity at the same time. A couple of years ago you told James Mustich that you were working on a contemporary novel. Is this that book?

CRL: No. But this book came out of that book, and that book was about contemporary China. I had gone to China and done research, and it was going to be focused on the factory cities along the Pearl River Delta, outside of Shenzhen. It was going to be a social realist novel about that whole world, and have an American connection, and it was just going to be this big, sprawling book about China. But after doing all the research — I really enjoyed it, going over there and seeing everything. I went into this cool factory and saw all the dormitories, this whole little world —

MN: What was your primary impression of it? Mostly depressing, or was it–?

CRL: It was not mostly depressing, and that’s one of the things that I think I drew upon for writing about B-Mor. It was okay. It wasn’t awful, not brutal Dickensian conditions. It wasn’t sleek or like something you’d see in Norway. It had sort of everything — a cafeteria, a tiny little infirmary, a dormitory where eight girls would live together in a room a little smaller than this, probably about 14′-by-14′ or 12′-by-12′. Eight people, so two four-person bunks. But high ceilings, I think by design, so they could hang their clothes as they dried. They did everything in this little room.

It’s not the kind of place that you would ever really want to stay, but I am sure a lot of these people from the provinces had very poor conditions growing up, so this might have seemed pretty decent to them. But I think you would still quickly feel as if this is a workplace, this is about efficiency. There’s no ornamentation. There are no nods to anything aesthetic. It just works, and it’s good enough. It’s sufficient.

They didn’t allow me to speak to workers, but I watched them. Doing some more research and seeing how they interacted, I felt as if it was a bargain they were making. “I’m going to up my standard of living to some middle-class comfort level or approaching that, I can send money back, but I am going to work like a dog, without any kind of fun. I’m going to be part of this, and put myself into it.” That’s I guess the sensibility of that, kind of putting yourself in a compliant situation.

MN: That comes across so powerfully in this book, the incentive to be compliant. You can really easily put yourself in that situation, and just think, “Well, I would do that, too, except I probably wouldn’t be able to clean a fish tank or maintain produce or whatever.”

CRL: You would learn. That’s the thing, all these people, these young girls, they came from these dirt villages, and now they’re making these little tiny motors. They were all trained to do their job. And they don’t have a very difficult job. It’s monotonous, but we all could do it. It’s a matter of just putting yourself in the mind-set of “this is my life.” That’s what was kind of chilling about the whole thing. About all factory work in general, but in the context of China–

MN: Living there and having it be not just a deadening day job that you go to, but actually the thing that is your life–

CRL: It is the life.

MN: The structure of your life.

CRL: Yes, yes. And that captivated me, in a way. That’s something that I didn’t realize I was going to learn. What I got out of it was that feeling. So I was going to write this novel, but I came back and I started writing it, and I was doing good journalism, but I was wondering, “What is the fiction aspect of this?” Sure, I have a character. I can get into her head or his head. But what’s really my angle here? Why do I really care? It’s not enough just to show what’s going on.

MN: In that prior interview, you spoke powerfully about the smallness of the characters’ worlds in your last book, these individuals caught up in the Korean War and other huge dramatic events. You said, “[T]here’s something poignant in watching an ant move…. She picks up this little breadcrumb that’s three times her size and just keeps walking. The more you watch that, the more you’re moved. Look at this modest but incredible scene of life.” And you mentioned being awestruck not just at political forces in the world “but also the acts of a single human being.”

One thing I find so fascinating and puzzling in a good way about this book is how you simultaneously managed to create this sense of the individual and this sense of universality. So it’s narrated in the first-person plural —

CRL: The “we.” That came about quite early.

MN: The title is taken from Julius Caesar, and the passage in Julius Caesar that it comes from is also in the first-person plural. “On such a full sea are we now afloat…”

CRL: I’ve been reading Shakespeare a lot lately, because I was bored on planes. I don’t like to watch movies on planes, so I thought, “You know what? I should just freshen myself up on some Shakespeare.” And I was reading Julius Caesar, I loved it, and I came across that quote, which is — he’s speaking metaphorically — it’s about opportunity and taking risks. Even though he’s speaking metaphorically, just the image of it, this tide, this wave that this little girl would be on. Does the wave come from herself, or does it come from outside? She seems so persistent and irrepressible in a certain way, and I love that idea of the sea rising, and that she was a diver, and I thought, “That’s perfect.”

MN: It really is. And it’s metaphorically apt, in the world she leaves behind. Another thing that fascinated me was the stuff about blood. I’ve been working on a long piece about ancestry, and thinking a lot about growing up around my father’s obsession with the “purity of blood.” And this comes up among the new China settlers in B-Mor, and the “native population” that was there. I love the part where the We finds out that a beloved aunt is mixed-race.

And it’s clear there was overt racism at one point in B-Mor, and the people who were living in Baltimore were marginalized and quarantined and slowly forced out, and now there’s this more insidious sort of awareness, and nobody really knows what it means. Then you bring in this character, Reg, who is C-free — free of a disease that sounds a lot like cancer, that plagues everyone else — and so there’s all this curiosity about him and his genetics among the Charters, because he’s mixed-race, and obviously so.

CRL: Well, I knew when I was setting the book in the former Baltimore that there would have to be some racial consciousness by somebody at some point, but it aligned very nicely with how I thought about these people who had come over, because so much of their identity is a group identity. That’s why the “we” is the We. But that communal identity only works if we can really identify the We. [Laughs]

MN: That’s what’s so fascinating also about the We here! I was thinking of, of course, Brave New World and 1984, but mostly I kept thinking of Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go and also the Joshua Ferris book Then We Came to the End. In both of those books, there is this deep psychological insight into the modern world and where we might be headed. And also, especially in the Ferris book, there is philosophical awareness of the way people behave in groups.

CRL: Yes.

MN: It’s very generous, but also incisive. I felt that here, too, and even more so because of these extreme conditions that you make feel so accessible and familiar. And then you overtly brought in the problem of “Well, what do we really know about Fan?” As you’re reading, you’re like, “Oh, it’s fascinating that this happened,” and then you’re like, “Well, maybe it happened, or maybe the We is just imagining it.”

CRL: Well, so much of the We’s interests — it has a lot of interests, but one of the interests is, “Who are we?” And the We is not authoritative enough to come down and say, “This is it.” So I wanted a We that, particularly in this question of blood and kind would have an anxiety about it.

MN: It also implicates the reader, even if you can’t relate to the specific thing that the We is talking about. CRL: Yes. That’s the nice thing about the We, first-person plural. It’s almost second-person address. It draws you in, and so you are suddenly looking… You are the one questioning, you are the one who is wondering. What is it about Reg, and how does he reflect me? Is it because he is mixed that he is so pure of C? What does that say about us? But these are all things that I didn’t really know when I started out.

CRL: Yes. That’s the nice thing about the We, first-person plural. It’s almost second-person address. It draws you in, and so you are suddenly looking… You are the one questioning, you are the one who is wondering. What is it about Reg, and how does he reflect me? Is it because he is mixed that he is so pure of C? What does that say about us? But these are all things that I didn’t really know when I started out.

MN: Did it take some time to figure it out?

CRL: It did. The We classically would be a chorus, and a chorus that had the benefit of a certain kind of omniscience and authority — and a moral authority. I thought, yes, there were going to be aspects of that to this We. But real reason why I wanted to do the We was that I wanted the story to be both an adventure tale, following Fan —

MN: Which it is. It has that propulsive adventure-story quality.

CRL: I wanted her to go out and discover the world, but also that each discovery would put into question some aspect of their origin point. I wanted the We to then be deformed in some way, as a moral, authoritative conscience. It’s a conscience, but it’s a conscience that doesn’t know what the rules of conscience are as we go through.

MN: That anxiety is fascinating. The We starts out very censorious of Fan, while being mildly sympathetic in some ways, and then increasingly becomes more and more sympathetic and identifies with her more and more, and then transforms her almost into a hero. Which people and cultures tend to do over time.

CRL: Partly, I think, it’s because once you start telling a story — because that’s what the We is also doing, it’s also telling a story — once you begin narration, the narration, in certain narrations, wants to let someone rise. It has to. If it doesn’t, then what do you have? Why are you telling this story?

MN: And the We more than anything else almost creates that need.

CRL: Yes.

MN: The world that you describe is so familiar in various ways. It feels, at least for people who tend to view things in an apocalyptic way sometimes (and I do), that we’re right on the edge of a world like that, a world where there are the Charters, the wealthy, privileged people, and the counties, who are the marginalized people who live in lawlessness with no recourse and no medical care–

CRL: No infrastructure.

MN: Right. Then there’s the in-between stage. Obviously, the B-Mor facility is much more regimented than the life of a typical office worker today, or even a factory worker in America. But it’s still recognizable enough that it really doesn’t feel like that much of a stretch.

CRL: Well, it’s that society’s version of the middle class. The middle class, but the middle class is so regimented, and that’s what’s scary about it.

MN: Yes, and if you won’t stay within the parameters that you’re allowed to exist in, you’ll be released into the counties.

CRL: That’s my anxiety about now. We all know and we all have the sense of how fragile actually our economic position is as individuals and — You read stories all the time about people who have a perfectly good, upper-middle-class life, and then suddenly, boom. Right?

MN: Exactly.

CRL: That and the income disparity, and that entails education disparity, healthcare disparity, everything.

MN: And the way that you write about that, especially the education and the healthcare and the insidious discrimination, it really could be about this moment almost.

CRL: It really could be– I never felt like I was writing about the future. These are all my very present anxieties. My other books have been about a person’s consciousness about who they are, how they fit into this world or this society. This book is the first book I think I really felt like I was writing as a citizen of this world, and letting in all my anxieties about the world, about the divisions in class and the gulfs in wealth, all those anxieties, and my anxieties about community, too, about the joys and also the really scary parts of having such a tight community.

MN: It’s remarkably thoughtful and generous in that way. I was constantly folding down the corners of pages in my galley so that I could go back later and ponder the We’s observations. I love the section about the rash of spontaneous group defiance in parks where word seemed to spread but no one could really pinpoint how, “as if we each had a solitary desire that should not be named but whose expression, once sparked, was so instantly enacted that it felt as pure and instinctive as fleeing from a house fire.”

There are so many beautiful, poetic observations about groups, their desires and tendencies. Without them, this would just be another — quite possibly brilliant, but another — ironic dystopian novel. I mean, there’s irony here, for sure, but that’s not the predominant feeling I get from it.

CRL: I’m glad you feel that way. Again, I didn’t set out to write dystopic fiction. That’s not the model in my head. I just had to set it in a certain place so I could address certain anxieties of mine — which are always about the dramas of a particular people. I’m glad you brought up that ant quote. That’s sort of how I guess I’m feeling about all of us more and more. Maybe I’m getting older, and I feel like I can cast myself against this huge screen, I’m seeing things more contextually than personally, more and more.

Someone asked me, “Well, you could have had it just in a first-person singular.” But I didn’t want one person’s voice, tonality, being. It’s not about personality in that way.

MN: Not like Native Speaker.

CRL: Right. It’s not about that. It’s not about one person’s view. I mean, Fan is an individual, but she’s not the same. We don’t know her the way that we know other heroes. And I purposely shied away from doing all the normal things that I would do for the protagonist.

MN: What are those things that you would normally do?

CRL: Well, we would get deep inside her head about this issue and that issue, so we’d get all the little nitty-gritty of moves of her consciousness. We’d get much more of her voice. She’d be much more of an actor. But she’s like a mirror to everybody she comes into contact with. She inspires them to expose themselves. I always think of her as like Nature. She’s just there. Then people react in certain acts. Like, “Look at that tree; I want to cut it down” or “Look at that tree; I want to dress it up.” But it’s all about what she seems to evoke in everybody she meets.

MN: She’s a very small woman who seems much younger than she is, and, as a small woman who, when I was younger, always seemed considerably younger to people than I was, I could relate to some of that. Obviously, I wasn’t like Nature. But I’ve become aware that people feel able to project things onto people who are small and seem innocuous.

CRL: Yes. Seem innocuous. But somehow, Fan inspires them. It’s not just projection, but it’s a certain kind of inspiration.

MN: Yes, I love that! She’s a hero.

CRL: Even if it’s dark inspiration sometimes. I was really fascinated by her. Someone asked me, “Is that the difference between a Western hero and an Eastern hero?”

MN: What did you say?

CRL: Maybe. I don’t know. But the Western heroes we know — in literature, it’s someone who is picaresque, larger than life, very vocal. And she’s totally the opposite of that. The heroes of my previous books are very Western, in a certain way. But maybe this one isn’t. And the We, who does have some personality and a modulation to their consciousness and person — it’s more tentative.

MN: On the subway here, I was imagining what a movie of this would look like. I think it would be a wonderful cinematic story.

CRL: I think so!

MN: I do keep thinking of her almost as a superhero, which is not how I felt when I was reading the book at all. But the more I’ve thought about it, the more she’s started to seem like that kind of character.

CRL: Yeah. Page by page, she’s just sort of there. She’s in place. Maybe that’s her gift, to be in situ.

MN: I’ve read that your father was a psychiatrist, and I’m wondering how you feel that this, if at all, has informed your own way of looking at people and your own writing.

CRL: I think it influenced me a lot, because of the sort of person he was, and maybe I’m a little bit like him. He was kind of bookish, curious about people. It wasn’t just that he wanted to be a psychiatrist. He actually wanted to be a psychoanalyst.

MN: I did read that, I think in Charles McGrath’s profile.

CRL: His language skills just wouldn’t allow it. It was impossible for who he was, a twenty-seven-year-old immigrant from Korea who had never spoken English on a daily basis. But when I was growing up — I was just writing about this for the Times — I read a lot of his psychology texts. I really enjoyed them. They were just great stories to me about all these strange characters, people with problems. Then later, when I was in college, I actually worked at a clinic, a psychiatric clinic, as a physician’s assistant, a nursing assistant.

MN: Did you like that?

CRL: I did. I would just sit with people. Most of the people weren’t very interesting in the sense that they just were totally out of it. But I’ve always been very curious about people, and I’ve always really liked people — the phenomenon of people. Even a person who is a total asshole, I still sort of appreciate them in a way that I think other people might not, just because they have an emotional reaction that precludes any kind of further study.

So I think the life of the mind and the character of the mind has always been something that’s been in my family and in my life.

MN: I wanted to ask you about that. For me it ties back into those questions of blood and inheritance and environment. Does that sort of thing get passed down genetically? Or is it a learned behavior? Or is it some combination?

CRL: I think it’s definitely a combination with me and Dad. I guess we’re both sort of patient, in a way, with people. I always felt he was very patient with people.

MN: That’s a constant through your books. There is this patience with people. Even the narrators of your first-person novels are, maybe at times to a fault, patient with people.

CRL: Yeah, they are.

MN: Do you feel like talking about what you’re working on now?

CRL: I think I’m going to pick up the China business, but in a slightly different way. It’s going to be more focused on this one character, a fellow who is a more entrepreneurial type, kind of a Horatio Alger type. This guy is a sort of world-beater.

MN: Which brings us back to the parallels between our world and the different economic classes in On Such a Full Sea, the counties and the facilities and the Charters.

CRL: We all know it’s happening, and yet there’s not really a lot of talk about it. I mean, there’s the Occupy people. But there’s not a groundswell of worry. It’s beyond me why people aren’t more worried about it. This minimum-wage thing is partly a worry about it. Now we’re really thinking, “Wait a minute, these people, they get minimum wage and then they need food assistance?” These are working people.

MN: The stuff where you see Wal-Mart having food drives for its employees.

CRL: I know! It’s no longer some Republican story about people who don’t want to work. These are people working two jobs. So what are we offering them in our society? Zero. All that stuff makes me crazy.

– December 4, 2013