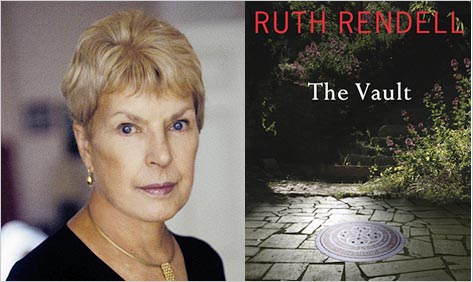

Ruth Rendell

After talking with Ruth Rendell, I can honestly say that she is the most civilized person who has ever robbed me of sleep. Books like The Bridesmaid and A Sight for Sore Eyes manage, in modern settings, the genuinely unnerving eeriness we hope to find—and rarely do—in the gothics that amused readers of earlier centuries. Rendell’s newest novel, The Vault, is the latest of her mysteries to feature Inspector Reginald Wexford, who debuted in her first novel, 1964’s From Doon with Death. It is also, unusual for her, a sequel, and even more unusual, a sequel to a non-Wexford book. The title refers to the hidden underground coal cellar that, in the finale of A Sight for Sore Eyes, becomes the home to three bodies. Opened up near the beginning of The Vault, the subterranean chamber has, somehow, become the home to four. Wexford, now retired from the Kingsmarkham police force and, with his wife Dora, living part of the time in London, is called in to assist on this baffler.

Though her focus in more than sixty novels—the Wexford series, the stand-alones, and the nearly operatic novels written under the name Barbara Vine—has been on crime and punishment, it seems silly to think of Rendell as a “genre” writer, particularly when we live in a time when literary fiction has become as much a genre as anything else. Her work adds up to a moralist’s cool dissection of crimes large and small, among the latter our everyday sins and vanities, and echoes Thackeray’s sentiment: “We may be pretty certain that persons whom all the world treats ill, deserve entirely the treatment they get.”

The author sat down recently in the offices of her American publishers for a conversation about her approach to writing and her fictional alter ego.

The Barnes & Noble Review: I made the mistake of reading this alone in an apartment at night.

Ruth Rendell: Oh, I see. You had no sleep all night.

BNR: Yes. A few of your books have gotten to me that way.

RR: [laughing]

BNR: What led you to a sequel, and to A Sight for Sore Eyes?

RR: Well, I don’t know really, but I was sitting in the room where there are a lot of books and I saw the various titles of mine and I saw A Sight for Sore Eyes. I thought well, you could do a sequel to that. It’s not a Wexford, of course. But it could be — it is as if Wexford walks into some sort of fantasy land, in a way. And I thought, well, why not have Wexford called in to do it? Because I also knew that I was going to have to retire him. Because he can’t go on like that, he’s getting too old. So, I thought, well, bring him to London because he likes London and he can enjoy himself and also be a sort of aide to this man, Superintendent Ede, and we would unearth—if you like—what’s happening at Arcadia Cottage. With a lot of my books you couldn’t do that because they’re not so open-ended.

BNR: No, they’re very finished.

RR: Yes.

BNR: Part of the attraction for readers of a detective series is they’re checking in on someone who they’ve come to feel is an acquaintance at least, possibly a friend. I want to ask: what is it that’s kept you with Wexford for almost fifty years now?

RR: Well, I like him, you know. And he’s me. I mean, his views are my views—on the whole, not invariably-—so I know him very well. I know that people like him. I mean, women are attracted by him, and it’s ridiculous, really, you can hardly understand that, why people feel like that about a fictional character, but they do. And men, I think, identify with him. So, that sort of kept me with it, and I knew that it was popular. And if I had an idea for a plot that was essentially a detective story, there it was, with Wexford. And then of course I have all the other [books], which don’t have much of a mystery, although I think they have suspense.

BNR: Wexford is a good man, and a humane man. One of the things I like about him is that he hasn’t softened in fifty years.

RR: Well, no, but he did soften a bit. I’ve been rereading the early ones, to remind me of various things that I ought to know, because I never make notes or have charts or anything like that. And I find that he was much harsher in those days, and tougher. He has softened a bit.

BNR: But he’s not sentimental.

RR: Well, no, but then I’m not. And he won’t be if I’m not.

BNR: That’s one of the things that I trust about your writing. There is, in The Vault, his less-than-pleased reaction to having to have his daughter and grandchildren come to live with him.

RR: Yeah, well…[laughing]

BNR: Which, although it’s completely believable, is the kind of thing that we like to tell ourselves that we’re above.

RR: Yes.

BNR: I find a lot of that in the books. Obviously there are crimes in the books, but there’s also a sort, a peeling back of the petty cruelties that we’re all guilty of.

RR: Well, I have a son, and I have grandchildren and there’s absolutely no prospect of them ever coming to live with me. But I know friends of mine, and I think it’s quite a common thing. And people don’t really like it. Sometimes they pretend to like it, that there’s nothing they like better, but in fact the honest thought is “Uh, my son’s coming back, I hope he won’t be more than a month” or something like that. Because we expect our children to leave us. We should do, it’s very bad for them as well if we don’t.

BNR: Do you think if yourself as a black-humor writer?

RR: To some extent. Yeah.

BNR: What amuses you? What makes you laugh?

RR: Wit. Not slapstick. Nothing like that. I never watch comedians on television, they mean nothing to me. Farce doesn’t mean anything to me. And I find it extraordinary—I mean, the banana-skin situation, I couldn’t possibly laugh at anybody having some kind of accident, it would leave me cold. Possibly sympathetic, but not amused.

BNR: What drew you to crime fiction in the first place?

RR: Well, in a way that was by chance. It was because the first book I ever wrote that was taken—although I’d written others—they were not taken and the first book I had written—that was From Doon with Death, which I really wrote for fun, to see if I could—was the one that my British publishers took, and the following summer was published here.

BNR: Were you an avid reader of crime fiction at the time?

RR: I was at the time. Not now, no. I never read it.

BNR: Who are the writers that were important to you and that are important now?

RR: All sorts of classical stuff. Dickens was important and George Eliot and the Brontës and people like that. And even Arnold Bennett. Thomas Hardy was my father’s favorite author, he used to read Hardy aloud to me when I was a seven-year-old, and it nearly drove me out of my mind. He was a West Country man, so he could do the accents of Wessex and so on and he used to read to me Under the Greenwood Tree and Far from the Madding Crowd, and I loved my father so I put up with it. But it put me off Hardy. I’ve read Hardy since and I quite rather like him. But I think, my father was a not naturally a cheerful person, not a happy man, and I really think that if you read Jude the Obscure, for instance, or even The Return of the Native, that would be enough to make you go and throw yourself in the river. Dreadful. But all that stuff I read, and I read Forster and Wells and, you know, I’ve read everything. I do still read everything. It’s hard for me to pick out writers, I read a great deal. So does Wexford.

BNR: Where do you think your understanding of obsessive behavior comes from? Especially since you’re saying that you share Wexford’s views and he stands out as such a balanced character in your work.

RR: He’s probably more balanced than I am, because, of course, if you’re writing something that’s sort of autobiographical in a way you tend to, in characters, improve upon your own. I don’t know if I am obsessive. Not really. I don’t think I am. But I am very interested in obsession. I am interested in the way it, of course, by its very nature it takes over a person. I’m interested in obsessive-compulsive disorder and that kind of thing. I am very tidy. I like to live in extremely nice surroundings that I keep tidy and in good order and in good repair. I know that I will go home on Monday morning and I will walk into my house, where my secretary has been living to look after it and look after my cat. And I will walk down the stairs into my large room at the back with the french windows and look onto my garden, of which I’m very proud which will be full of autumn flowers. And I like that. I like it to be like that. I would find it very, very troubling to be surrounded by mess or something that hadn’t been done or mended or put right. So there’s a bit of obsessive if you like.

BNR: I was thinking of this, too, in terms of a quotation you gave The Telegraph, from Arnold Bennett: “Humanity treads ever on a thin crust over terrific abysses…”

RR: Yes. I feel like that a bit. I don’t feel like it all the time, of course not.

BNR: No. But the work is about those abysses opening up.

RR: That’s right. It is.

BNR: Do you know what it is that first led you to be aware of them?

RR: Probably Arnold Bennett, I should think. [laughs] I’m actually quite a cheerful person. I don’t go through life thinking that I trod on this crust and it’s going to split open for me. But I’m aware it could happen. I’m very much aware that, you know, you woke up in the morning and you feel the day is going to be rather good. But I am aware that a crack could appear in it and then it would open and—everything would be different. Everything. Everything. One’s whole life is changed.