14 Authors Discuss Identity, Revisiting the Past, and More in September’s YA Open Mic

YA Open Mic is a monthly series in which YA authors share personal stories on topics of their choice. The aim of the series is to peel away the formality of bios and offer authors a platform to talk about something readers won’t necessarily find on their websites.

This month, 15 authors discuss everything from stolen homes to adoption. All have YA books that either release this month or released in recent months. Check out previous YA Open Mic posts here.

Sonia Patel, author of Jaya and Rasa

Identity formation should flourish in adolescence. Erik Erikson, a developmental psychologist, said that an adolescent must successfully resolve the stage of “identity versus role confusion” by experimenting with different roles, activities, goals, values, and behaviors before moving onto the next stage, the adult stage of “intimacy versus isolation.” Teens who get stuck in role confusion are less likely to form strong relationships. They are left lonely and isolated.

I was one of those teens.

From the outside, our Gujarati Indian immigrant family seemed okay. My father, backed by the patriarchal aspects our culture, cast me in the typical Gujju role of the obedient, eligible, straight daughter who would become a physician. I played my part well. After all, I was grateful for the opportunities afforded to me as the first person in my family to be born in the United States of America.

Yet no one saw the other role I was forced to play—my father’s surrogate wife—or the role my mother was left with—my father’s servant. And so my identity became nothing more than an object to serve my father’s intimate needs. Shame and rationalization kept my lips sealed.

I grew into a lost, lonely, empty shell of an adult. I couldn’t sustain deep, meaningful relationships with people, particularly women. I didn’t know how to set boundaries with men who wanted sex. I made poor decisions trying to re-create my dysfunctional relationship with my father with other men. I ended up hurting the people who cared about me the most. In the aftermath of all that chaos, I hit rock bottom.

But in retrospect it took this level of anguish for me to break free of the hardwired, oppressive chains of my family of origin. I finally had my chance to work through the stage of “identity versus role confusion” the correct way.

And I have. I’ve established that I’m not an eligible object to serve a man’s needs. I’m not straight. I’m not just a girl. I’m not just a physician.

I’m a fierce person. I’m queer. I’m a child and adolescent psychiatrist who is passionate about helping teens find their way out of severe emotional turmoil. I’m a parent who is committed to providing a safe environment within which my children will determine for themselves who they are. I’m a spouse who has finally learned how to love someone else completely and unselfishly because I’ve belatedly learned to love myself. I’m dedicated to pursuits that bring me joy—rapping and writing raw stories.

The real me has got some serious flava’

I’m a mental health trailblaza’

And a YA diversity game changa’.

Akemi Dawn Bowman, author of Starfish

I’ve spent most of my life never really feeling like I was “enough.”

Good enough. Smart enough. Asian enough. White enough.

I was never the best flute player.

I was never the fastest runner.

I was too talkative or not talkative enough, and always at the wrong time.

I was always scared to be around people, because I was terrified of the flaws they might see that I still hadn’t discovered.

I felt afraid of the world, and how big it was, and how many times I was bound to get things wrong.

I was afraid I’d spend my life forever letting everyone down, including myself.

And eventually not feeling like I was enough became my own monster. It chewed at my heart, until there wasn’t much of it left.

And then my daughter was born, and my world changed. Because she was so much more than enough—she was everything. And I was everything to her.

And I knew then that I had to break the cycle. If I wanted her to grow up loving herself—if I wanted her to believe she was perfect just the way she was—I’d have to believe it myself.

So I stopped thinking I wasn’t enough for the world, and started believing I was enough for me.

And the strangest part?

It wasn’t hard at all.

Because it turned out, I was enough for me all along.

It just took a monster and a baby to realize it.

Ismée Williams, author of Water In May

When I was young, we couldn’t travel to my mother’s Cuba for vacation. Instead, my blond, blue-eyed brother and I would run around the beaches of Mexico, speaking a mix of English and Spanish depending on our company. One summer, I was by the ocean reading when a dark-eyed boy came over and joined me. In perfectly cultivated English, he introduced himself as Carlos, asked where I was from, and told me he came to the resort every year from Mexico City. He was friendly and had beautiful eyes so when he asked if I wanted to go for a drink I rose and followed. We slipped into the pristine pool, heated from the long day in the Mexican sun, and swam to the submerged stools underneath the palapa bar. Carlos was over eighteen. I was not. The bartender, Juan, was a friend of his so I could order whatever I wanted. I requested a virgin piña colada anyway. It came in a cool coconut with a toothpick-spiked cherry. We drifted off the stools, Carlos swigging a Pacifico, me sipping coconut milk foam through a straw. Carlos was asking about New York when two guys greeted him with shouts of “Buey!” and said, “Hello, nice to meet you,” to me in thickly accented English. Carlos was asking if I’d join him for dinner when his friends returned from the bar. “So,” one murmured in Spanish. “What’s up with this chick?” I took another sip from my straw as Carlos replied, also in Spanish, “We’ll see. Thought I’d have this Americana in my room by now. Maybe Juan needs to spike her next drink?” The three of them chuckled. I handed the empty coconut to Carlos. “Could I have another?” He winked at his friends. “Of course.” I floated onto my back, switching into my mother’s native tongue. “But make it a Diet Coke.” One of the guys choked on his beer. The other’s mouth fell open. Carlos’s beautiful eyes sharpened as he looked me over. “I didn’t know you spoke such lovely Spanish.” He didn’t bother with English anymore. I shrugged. “You never asked.” I didn’t bother with English anymore, either.

When people find out I’m half Cuban, the usual response is, “Oh. I can see that.” Meaning, they didn’t before. My half-ness never bothered me much, though. I felt comfortable in situations I otherwise might not have. And there’s fun to be had with the shock factor. Even if your family is all from the same town, speaks the same language, and prays to the same god, chances are you’ve been misjudged, too. Maybe you’re a girl who knows more about cars than the dealer or a tall person who doesn’t play–or even like–basketball. We should remember what that feels like. Because we need to try not to prejudge others.

Eric Smith, editor of Welcome Home

Eric Smith, editor of Welcome Home

I can still feel that fall down the hard stairs of my junior high school. I scrambled to my feet, my back against the wall, my nose already bleeding all over my shirt.

“Don’t you ever think of talking to me like that again.” He snarled, passing me as he rushed down the rest of the stairs.

Seconds earlier, I’d finally snapped.

He’d muttered, “At least I have real parents” in the hallway, and I tried to stand up for myself for once, sputtering out a poorly chosen array of swear words.

And he threw me down the stairs.

As I collected myself, another student hurried down and helped me gather my things.

“What were you thinking? He could have killed you.”

“I’m…not going to let people talk to me like that anymore.”

“You need to choose your battles. That ain’t worth it.”

The “at least I have real parents” line was a popular one growing up. I’m not sure why. My Mom and Dad sacrificed so much so they could bring me home. They always said that people were afraid of what they didn’t understand, and if I was going to fight back, to fight back with my words.

I have the realest parents.

I think 12-year-old me almost had a breakthrough that day, but I shut down. Choose your battles, right? I continued to ignore the jabs, until they stopped in high school. I balled all the hurt up, and only really started digging in a few years ago, after a particularly heated moment in pre-marital counseling, when I shouted, “mind your own business!” at our therapist in response to discussing being adopted.

My wife held my hand. And I realized I was still that afraid kid, but I’m not any longer.

And no one talks to me like that anymore.

But I wish I’d used my words sooner. Don’t be afraid to use yours.

Jessica Cluess, author of A Poison Dark and Drowning

I was driving through Oklahoma wearing half of a jester costume when I found a dog by the side of the road. There’s a reason for the costume, and Oklahoma. I’d just graduated from college, and gotten a job touring the country in a school production of Cinderella. Four shows a day. Three hundred bucks a week. Drive the van yourself.

We were heading to Tulsa when we found the puppy. She was a pitbull/chow mix. Likely a fighting dog they didn’t want. Covered in fleas, but very kissy.

While we performed, the puppy ate chicken fried steak in the administration office. Then I had to sneak her into the Days Inn inside my backpack. While I checked in our troupe, she kept kicking me. I hoped she wouldn’t pee.

She didn’t.

Finding a no kill shelter can be surprisingly difficult, so while Kate and Alex (the other actors) called around, I gave the puppy a bath and some more food. We’d stopped off at Walmart for flea shampoo, and impulsively I’d purchased a squeaky blue hippo toy. I dreamed of never finding a shelter, and having to take the puppy on the road for another two thousand miles. Maybe work her into the show: Cinderella’s magical dog. Alex, who played the prince, loved the idea.

Kate, who was Cinderella, had to be the voice of reason.

Eventually, we got the puppy into a humane shelter. We filled out the paperwork, kissed her goodbye. The instant we gave her to the shelter lady, the puppy fell asleep. She knew she was safe.

We named her Shenandoah after a John Denver song on the radio. Good thing we chose that one, because Alex wanted to name her Monkeyhead.

Before we left, I gave Shenandoah her blue hippo. I hope she still has it.

Katherine Locke, author of The Girl with the Red Balloon

When I was in third grade, I thought I was half-dragon. And when I was in fourth grade, I started reading Animorphs, so I decided I was a half-dragon capable of morphing, too. My best friend, Jessie, and I would walk around the playground together, glaring at kids who had been mean to us, and hissing, “YEERK” at them under our breaths. Unsurprisingly, this didn’t help either of us make more friends. Jessie, like me, was also a half-dragon who could morph. But she was a different type of dragon, which explained our fights. She was a forest dragon and I was a marsh dragon, and our species didn’t get along.

On a family vacation at age ten, I pulled my cousins to the side and said, very dramatically, “I have something to tell you.” And then I paused, both for effect and to let my parents pass as they were mere humans who couldn’t know. “I’m an Animorph. I’m also still a dragon. But I’m also an Animorph.”

My cousins nodded solemnly back at me. “We are, too.”

We wore swimsuits to bed (to morph, duh), narrating our morphing adventures (while obviously still being in bed. We were frequently bats) and biking into the woods, in swimsuits, so we could morph for battle. As you do.

Back then, we took stories into our bones. My cousins, siblings, and I had a secret spot in the woods, loosely modeled after the picture book Roxaboxen and middle grade novel Bridge to Terabithia. My siblings and I had imaginary horses that we raced, competed, and rode throughout the day (even “cantering” as we walked) after I read National Velvet and Velvet did something similar. What we read we incorporated into our own lives, blurring the line between fiction and reality and wholeheartedly embracing imagination.

I can still see that secret spot in the woods, if I’m looking hard enough. And when I sleep in the bunk room, I remember sleeping on the top bunk, whispering to my cousins that I was starting to morph. And when I’m down at the shore and I see pickle grass, I remember how that was my dragon species’ favorite food. And when my enemies cross me, there’s still a part of me that dismissively hisses at them, Yeerk.

Mitali Perkins, author of You Bring the Distant Near

The old man blocked my path. “What do you want?”

“My grandfather lived here,” I said. “May I see the house?”

I didn’t tell him my real purpose. Because of enmity between Hindus and Muslims, my family fled to India during the war before I was born. This man had commandeered the property, and my Grandfather had died a bitter, cheated man. I was here to make peace.

I glanced around. I hadn’t expected it to be so…beautiful. Sunlight sparkled on the pond. Mango trees were heavy with fruit.

“I won’t stay long,” I said. He grunted and stepped aside.

I paused at the threshold. My grandfather had flung this door open hundreds of times, calling out my grandmother’s name. Now I was a stranger from far away.

Suddenly, the door flew open, and a circle of women drew me inside, laughing and chatting. I admired sleeping babies and tucked cash under their pillows.

The man interrupted. As he ushered me outside, an ancient hatred rose inside me. Help, I prayed. I came to forgive him, but I can’t.

I turned to wave at the women, and saw two white doves perched on the roof of the house. They were as still as statues, watching me.

“Did you find any pictures or letters belonging to my family?” I asked the man.

He didn’t meet my eye. “I burned them,” he muttered. “I am…sorry for that.”

I took a breath. The doves didn’t move. “All right,” I said. “May I pick a few mangoes?”

We gathered the fruit together. As the car drove away, I didn’t notice the ponds, trees, or land. The last things I saw were the wave of an old man, and two white doves perched on the house I had given away forever.

Zac Brewer, author of Madness

“Oh, look. It must be Halloween.”

That’s what a grown man said about me, keeping his voice loud enough so that I would hear him, as I walked through a bookstore in Kentucky. It was a rather conservative area and my hair at the time was black and bright red. I was dressed in black, with pyramid stud accents. But it struck me how rude it was, and how ruder it was that the other people in the store laughed along with him. I held my head high and said nothing, which isn’t like me. Normally I’d quip back. But I was outnumbered and I knew it. So I left…cursing how much that stupid moment had hurt my feelings.

I wish I could say that I was a teenager and that I totally forgot about that moment until just now, but no. I was thirty-four years old and it still stings me today. Maybe it hurts because grown people were acting in a manner that no one should act, bonding together through an attack on someone whose appearance they didn’t care for. Maybe it hurts because my ego is bruised still and I wish I could turn back time and say something that would stop the laughter, something that would bring a look of shame in their eyes. But what matters is that ten years later, it still hurts that some random guy in a bookstore laughed at my hair and the way I dress.

It just goes to show you that your actions—or your inactions, for that matter—count for something. What you do or don’t do in this life will affect others. It will affect you. And you may never realize, no matter what side you’re on, how much a small moment can affect a person.

Shaun David Hutchinson, editor of Feral Youth

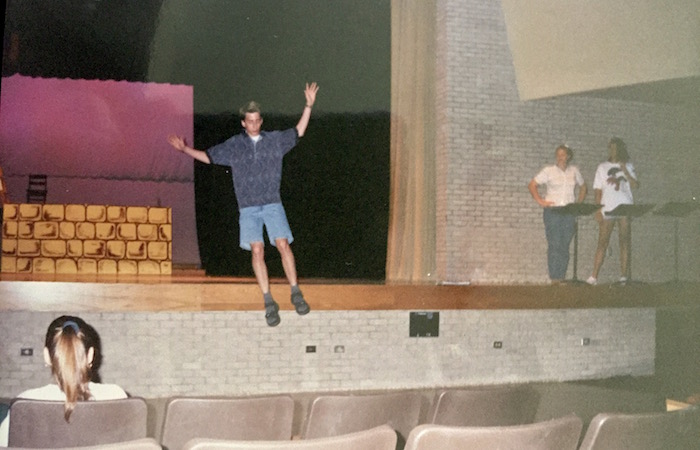

In high school I was bitten by the acting bug. I played a misfit Renfield, a saucy Aslan, and a sniveling Vizier’s son, among other things. I also played Robin Hood, and I was dedicated to it. I attempted to learn how to fence for the big fight scene, I worked on my lines nonstop, I tried to project a heroic do-gooder worthy of wooing Maid Marian.

I was pretty terrible.

In a pivotal scene, the dastardly Sheriff of Nottingham was to stand atop a two-foot high box with Maid Marian as his hostage, and I would run across the stage, leap onto the platform and yell, “Never fear, Robin’s here!” before launching into my big showdown with the Sheriff. The day of the show, our director decided to surround the box with potted plants and trees to give the illusion of forest. It wasn’t fooling anyone.

You know where this is going don’t you? So it was opening night, everything was going well, no one had missed their lines. I was feeling really great. Confident. I stood in the wings waiting for my cue. When I heard it, I sprinted across the stage, poured all my energy into my legs, and leapt onto that platform.

It was beautiful. I sailed. I soared. And then I landed. On those leaves. I slipped, flying through the air once again, and landed on my butt. I slammed my head against the platform. Everything hurt and I felt like I was going to puke.

The audience was silent. The Sheriff and Marian stood over me with horrified faces. And then, still flat on my back, I yelled, “Never fear, Robin’s here!”

Because even when life knocks you on your butt, the show marches on.

Cat Winters, author of Odd & True

I posed for my very first author photo in 1998, when I was twenty-six years old. San Diego Writers’ Monthly, a magazine that existed at the time, wrote to tell me they’d be publishing an excerpt of my novel-in-progress, and they asked me to send an author photo. I donned my bright red sweater, styled my cool 90s hairdo (which was inspired by “the Rachel” from Friends), and put my husband in charge of taking the picture in front of a fence in our side yard. I thought to myself, “This is finally it! I’m about to leap into my much-awaited writing career.”

I’d been writing stories and poems since childhood. I first started submitting my work to publishers—and receiving rejection letters—when I was a young teen. Family members and teachers urged me to follow this career path, and I wrote during every spare moment I could find, often working late into the night, revising, perfecting, giving up time with loved ones.

That 1998 publication of my novel excerpt didn’t launch me into instant career success. It would take me thirteen more years, five more manuscripts, two different agents, and countless moments of doubt and despair before I’d sell a book to a publisher. That book happened to be my YA debut novel, In the Shadow of Blackbirds, a 2014 Morris Award finalist.

When I look at my 1998 author photo today, I want to tell that young version of me the same thing I tell aspiring young authors at my talks: Just because you don’t succeed right away, it doesn’t mean you’ll never succeed. Writing, just like any career worth having, requires time, patience, luck, tears, perseverance, and incredibly hard work. Most overnight success stories actually take years.

Mine took decades, but it was worth the wait.

Axie Oh, author of Rebel Seoul

When I was 19 years old, I studied abroad in Seoul, South Korea, and got into a fight at a K-pop concert.

In South Korea, each of the major broadcasting companies has their own weekly music show where artists perform to promote their music. I snagged access to one of the shows through a family connection, and invited my friends along. One friend, a girl from China, was a huge fan of the headlining artist, and she brought a portrait of the artist to the concert that she’d painted herself!

We were seated early in front of the small stage, and then they let in general admission. Now, for these music programs, general admission is usually comprised of fan clubs of the artists. So, there we were, surrounded completely by fans with posters and glow sticks and noisemakers.

The concert was amazing. As the last artist took the stage, my friend whipped out her painting and raised it in the air. Then, suddenly, a girl grabbed it out of her hand from behind her and ran. For a moment, we were all stunned. She stole a painting! Who does that? Then fury overcame me.

I chased her down.

“Give it back!” I yelled.

The girl said, “No!”

I lost it. I never raise my voice, and there I was, screaming at this girl at a K-pop concert. Everyone was staring, but I didn’t care.

We got it back.

Afterward, another friend said to me, “Unni (big sister), you were so cool!” I don’t know about cool, but I was definitely hot-tempered that night!

Anyone who knows me knows I’m calm and more silly than not. Yet this story reminds me that I also have the will to act. Advocating and supporting others empowers not only them, but also yourself.

K.M. Walton, editor of Behind the Song

I keep a lot of ridiculously important things, boxes and crates full of my past. No one else understands the importance of saving the pebble I nervously played with during my first “real” kiss. That meaningful piece of stone lives with my cream polyester eighth-grade graduation dress and my Yoda pencil box.

The reason I have the peculiar desire to save life’s trinkets can be blamed on my father. As a little girl, I vividly remember playing with my father’s memorabilia. His miniature camera, the small worn-out box filled with Boy Scout pins and patches, the little guy made from a roll of Lifesavers. They were my father’s memories, his treasures tucked neatly into his night table drawer.

It would be nice and flowery to tell you we had the perfect father/daughter relationship, but the reality was that we did not. When I was a little girl he was an excellent daddy, but when puberty came for me, affording me a body in rebellion, my father shut down. I had questions. And opinions.

I remember wanting to talk to him about who I was, what my dreams were. I wanted his advice, from a guy’s point of view, to help me skip through the landmines of adolescence. I wanted tight hugs to reassure me and silence my self doubts. I wanted the dad from Sixteen Candles.

I blamed him for the father he wasn’t.

As I grew into an adult I continued longing for a close relationship with him. Spring of 1997 brought the birth of my first child and my father’s diagnosis of cancer. Within two weeks of each other. Close to the end, he gave me his night table treasures, one of them being my birth announcement cigar. He fought for eight grueling months and slowly lost the battle on October 25, 1997, at the age of 51. Those events forced me to take a deep look at my father.

He was a man who did love me but didn’t know how to love me. He was a man whose deep feelings lived in what he saved, a man who moved slowly through life weighing his choices with precision.

Eventually, I realized I’d spent years being angry with him for all that he wasn’t. This, of course, blinded me to all that he was.

Chelsea Bobulski, author of The Wood

I’ve always been in love with love.

Growing up, I rooted for the prince and princess to end up together, for the next-door neighbors to realize they were more than friends, and for the star-crossed lovers to get those stars aligned already! Even so, I never would have guessed I’d find my own soulmate when I was just fifteen years old.

The boy who would become my husband showed me everything love is supposed to be. Our love and friendship grew at the same time, at the same pace, until we were not only deeply in love with each other, but had become each other’s best friends. There was so much uncertainty at that young age regarding what the future would hold, but what we did know, the only thing that made perfect sense in our world, was that we didn’t want to spend our lives with anyone else.

It wasn’t always an easy road; not everyone took our love seriously. Who finds their soulmate in high school? Are soulmates even a thing? We were told to date a lot, try out different relationships to see which one fit. But we already knew. This was it, and we weren’t going to let anyone tell us differently.

That’s why I love writing YA, because it was in my own young adult years that I met the boy who, after college, would become my husband, and, after that, the father of my child. Others doubted us because of our age, but we never did. Much like Romeo and Juliet, who many critics still say were too young to know what real love was, we knew what we’d found was the once-in-a-lifetime love most people search for their whole lives.

Thankfully, unlike Romeo and Juliet, we got our Happily Ever After.

And we haven’t looked back since.

Jus Accardo, author of Omega

Jus Accardo, author of Omega

I’ve always been quiet and shy. I tried to get through school with my head down. Somehow that just seemed to make me an even bigger target.

The first time, they used words. It was awful, but I refused to give them satisfaction. If I simply ignored it, they would go away. That’s what the teachers told me. Just bullies. Kids being kids. Over and over…

They were wrong.

Over the two and a half years I spent in high school, they used everything from their fists and outrageous scare tactics to lit cigarettes and knives. I still have the scars. Some of the adults at school knew what was going on. The science teacher watched them poke me with X-Acto knives and touch me. He’d turn away when they threw rocks during class. I still see him all the time at our local diner. It may not be very big of me, but I hate him just as much now as I did back then. I’m human, after all.

I went to the guidance counselor. The nurse. Even the vice-principal. They said I was looking for attention. Said I should have a talk with these kids. Insisted it wasn’t as bad as I made it out to be. If you’re being bullied, don’t ever let anyone make you second-guess yourself. If you’re hurting, there is a problem.

In my junior year it all changed. There was a fight. I didn’t start it, but I didn’t stand there and take it that time, either.

That single act of self-defense got me kicked out of school. My parents found out the truth—they didn’t know how bad it had gotten because I hadn’t told them. I was ashamed. Worried that they wouldn’t believe me, either. Of course, they would have.

I wasn’t alone, and neither are you. Please, never ever forget that.