Harry Potter: A Beginner’s Guide to Evaluating Authority

“I want to teach my daughter to resist,” my friend said. “She’s going to grow up in a time when it’s going to be important for her to recognize that just because someone has power, that doesn’t mean she has to listen to them.”

“I want to teach my daughter to resist,” my friend said. “She’s going to grow up in a time when it’s going to be important for her to recognize that just because someone has power, that doesn’t mean she has to listen to them.”

I nodded. I knew what he was saying. It’s always been important to question authority, but this is a time in which anyone can see complacent obedience is simply not an option.

“But I also want her to listen to me,” he added.

“As long as you deserve to be listened to,” I said.

He laughed and nodded.“I guess that’s the thing, right? I want her to be able to tell who she should listen to, and who she shouldn’t.”

I shook my head at him. “Didn’t your family just finish reading Harry Potter together? You’re already on your way.”

<>

Harry Potter is not a resistance manual. Harry Potter is a guidebook.

One should probably not read Harry Potter in hopes of finding a way to form a cohesive, successful resistance group. There are good cues in there — educate yourself, maintain secrecy at all costs, undermine the illegitimate regime at every opportunity. But the real trick lies in the use of the series as an entry-level resource to help one learn to identify the legitimacy of authority figures: should someone be trusted? Should they be followed? Should they be in power at all?

Over the course of seven books, we learn to read annotated colorplates depicting different types of authority figures, thus developing skills to help us identify types of authority in the wild. This is why so many discuss our current political climate with allusions: “this person is just like [insert Harry Potter Character]”. These are tools we know how to use.

What follows is not an essay about He Who Must Not Be Named, because it is not an essay about anything so banal as evil. If that was all we were meant to learn—follow good, reject evil—life would be simple, and Harry Potter would be boring.

What follows is also not a comprehensive examination of the taxonomy of Rowling’s authorities. Rather, it is an overview of the way her work has taught a generation of readers how to decide who deserves fear, and who deserves respect; who deserves power, and who deserves to be unseated; who deserves obedience, and who must at all costs be disobeyed. Because Harry Potter is not, at the root, a series about good and evil, or right and wrong, or easy answers. It is about authority, legitimate and illegitimate. It about the questions we must ask before we obey.

It is about what happens when we choose not to ask those questions.

The first authority figure we meet in the Harry Potter universe is Uncle Vernon. He is in charge of his household; he is in charge at his job. He blusters and shouts. He is the boss. Just ask him. He will tell you so.

For most of his life, Harry Potter is under the impression he has no choice but to recognize that authority. He is powerless. He is alone in the world. There is nowhere for him to go, and so he respects the authority that insists upon itself in his life.

But then, a window to another world opens. Harry learns he has been lied to; not only was this other world concealed from him, but his own identity as he understands it is a fiction. Uncle Vernon, the authority figure and the chief author of these deceptions, says Harry may not jump through the window into this other world. He says, in fact, the other world cannot exist at all.

In this crucible moment—in a cottage on a rock in the rain, with a half-giant bellowing, and a freshly pig-tailed cousin wailing—Harry learns for the first time he can reject authority. He recognizes the illegitimacy of Uncle Vernon’s dominion over him. This is a person who does not deserve to be in charge, because he does not use his might well. He is not responsible. He is not trustworthy. He is not a person who ought to be in charge.

Harry recognizes this, and in an act of supreme disobedience, he leaves. He goes with the half-giant stranger. And when the door to the tiny cottage on the rock in the middle of the sea closes behind him, Harry Potter is engaging in his very first small act of resistance.

This is the lesson we learn from Vernon Dursley: Power alone is not sufficient to command obedience, and no authority is truly unshakeable.

Briefly—Hagrid is not an authority figure. Technically, he ought to be an authority figure—He is a staff member at Hogwarts, and an adult. But he isn’t a grownup; he is loving and loyal, but he is also stunted and irresponsible. He drinks heavily, even when he is meant to be the person in charge, and he loses things, and he tells secrets. The students at Hogwarts recognize this, and they treat him with affection or disrespect as they would a peer.

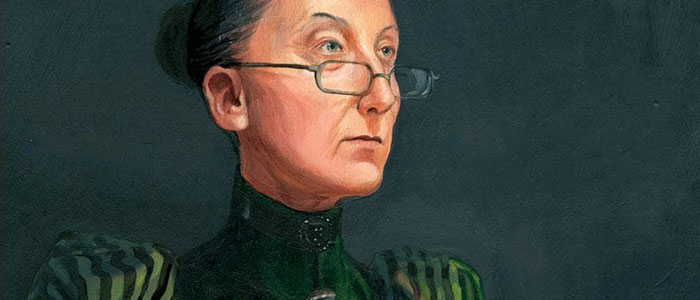

Hagrid demonstrates the fact that adults are not always grownups. He is also a crucial contrast to the series’ most evidently legitimate authority figure: Minerva McGonagall, O.M. (First Class).

Like Vernon Dursley, McGonagall is an intimidating figure. Unlike Vernon Dursley, her formidable presence derives not from bluster, but from the validity of her authority. She is worth listening to not because she is threatening, but because she is accomplished, wise, and fair. She makes a transparent effort to avoid favoritism. She demands hard work from her students, and she rewards their efforts according to the social contract she establishes with them.

This is a clear and comprehensive model of legitimate authority: we should respect people who are aggressively competent and dedicated to fairness and justice. This is demonstrated clearly in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, when McGonagall stops the ostensible Alastor Moody from bouncing a ferretized Draco Malfoy down a hallway. While the scene is presented as comedic, and the student being tortured is, by all definitions of the phrase, an absolute shit, McGonagall sees an abuse of power and uses her power to stop it from occurring.

While comeuppance can be satisfying to observe, McGonagall’s actions serve as a demonstration of power as it is meant to be used. When those in positions of power enforce just treatment of those they dislike, one can rest assured their authority stems from a sense of justice rather than a sense of relationship. There’s no need to stay on McGonagall’s good side in order to experience justice in her presence; even when she is angry at someone, she will treat them fairly. This reliable fairness makes her an authority figure to be trusted, and she is treated accordingly. Even when she errs, she commands deep respect.

This is the lesson we learn from Minerva McGonagall: Those who deserve to be followed will not demand your respect—they will earn it through a commitment to justice. And if they neglect justice in pursuit of their own personal satisfaction, then there can be no trusting the kind of justice to which they are committed.

Minerva McGonagall has a significant well of institutional authority backed by her intellectual authority. In contrast to this is a recipient of wasted institutional authority: Cornelius Fudge.

A coward and a hypocrite, governed more by fear than by a sense of responsibility to his office. A man who loves power for the sake of power, rather than power for the sake of the good that power can be used to accomplish. A man who consistently fails to rise to meet the demands of his office. An exemplar of unsound authority.

His dedication to the illusion of legitimacy is revealed by his treatment of the falsely accused Rubeus Hagrid during the opening of the Chamber of Secrets. Fudge demands Hagrid’s imprisonment in the human-rights-abuse nightmare that is the wizard prison Azkaban, arguably bypassing due process in his effort to provide evidence his office is addressing a threat. He subjects an innocent man to psychological torture in an attempt to prevent criticism of his ability to govern. It is immediately evident in this decision that Fudge values power, and will not hesitate to betray those he should be serving in an effort to preserve his access to it.

Fudge’s undeserved claim to authority is also underscored by his deliberately obtuse refusal to recognize the rise of evil in his empire. When he chooses to deny Voldemort’s return to power, he reveals his cowardice. His willful ignorance, his denial of eyewitness testimony, his insistence that everything is fine: these demonstrate the danger inherent in trusting an invertebrate with institutional authority. Because Fudge bends to fear and looks only to the preservation of his position, he puts the people he leads in grave danger.

Lives are lost because Cornelius Fudge is not worthy of his role—but, perhaps more importantly for our purposes, lives are also lost because people respect his position, regardless of his worthlessness. They carry out his instructions and follow in his wake, even as they witness his failure to lead responsibly. Voldemort is able to rise to power because those who follow Fudge do not take action to prevent his ascendancy. Thus, we bear witness to the consequences that arise when institutional authority is respected without regard to the virtue of those who wield it.

This is the lesson we learn from Cornelius Fudge: Death, unjust and preventable, is the result of a refusal to question authority.

Institutional authority isn’t the most important type of authority. It is an authority that shapes the actions of nations and governments, and influences law. It is rarely the type of authority that shapes hearts. That is the role of relational authority.

Enter Molly Weasley.

Molly Weasley is ostensibly powerless. She doesn’t hold a position in the Ministry of Magic, or even at Hogwarts. She is in charge of a family. She is a mother. She has children and a husband and a household, and they all rely on her. She has no institutional authority at all.

Even so, it can’t be denied she holds a great deal of authority in the lives of those who know her. In her household, her word is law. She is a benevolent dictator; she uses her power over those around her to help them flourish.

Molly Weasley is consistent, trustworthy, and nurturing. She uses her power to encourage those under her influence to be strong and kind, thoughtful and brave. She encourages them to be better versions of themselves, even when it means they aren’t doing precisely what she’d like them to do. She requires respect, but not unquestioning obedience. She struggles openly with the impulse to protect the people she loves, even as she recognizes the danger they’re in is necessary to pursue justice; this is evident in her attempts to keep her youngest children from participating in resistance activity, even as she supports her older children in their work.

In so doing, she models responsible use of authority, and molds the personalities of key figures in a successful resistance. When her sons steal her husband’s car to rescue a friend, she is angry at them, and they submit to her punishment while maintaining a firmly rooted conviction they have done the right thing.

This provides a crucial window into the way her loving, consistent application of her power over her household molds strong, resistance-oriented minds. She provides her children with a framework for doing the right thing even in the face of certain punishment. Her punishment comes not because she is embarrassed by them, and not because they have disobeyed her; rather, it comes because of the danger to which they have unnecessarily exposed themselves and others.

This is the lesson we learn from Molly Weasley: break the rules to do what is right, but break them responsibly. Above all, do what is right, and do it well.

Molly Weasley’s edict of personal, moral responsibility stands in direct contrast to the irresponsible application of authority that can be found in so many other places in Harry Potter: obey the rules because they are the rules, and the rules will tell you what is right. The person who made the rules will tell you what is right. They are in charge because they are in charge, and their tautological authority should be enough for you.

This is the framework that undergirds the woman who is plausibly one of the worst villains ever written in genre fiction: Dolores Umbridge.

Here, witness power qua power. Here, witness absolute corruption. Here, witness the insidious harm that is the direct result of corrupt institutional authority.

Umbridge is a landmark figure in a taxonomy of authorities, because she does not announce herself as corrupt. She announces herself as reasonable, thoughtful, deserving of respect and trust and admiration. To the savvy observer, this itself is paradoxically suspect: those who are deserving of obedience do not need to tell anyone they are deserving of obedience. But those who will demand unflinching deference need to tell themselves they are deserving of the power they hold, and so Umbridge makes sure everyone is aware of her righteousness. It is critical to her use of her authority: the universal understanding that she deserves all this power, and more.

The problem with this kind of authority figure arises at the first sign of disobedience. For unquestioning deference to be deserved, the bearer must be infallible; if they are proven to be wrong at any turn, their access to unquestioning deference comes into question. As such, any sign of dissidence must be swiftly addressed. When Harry Potter brings facts to bear, and those facts do not align with Umbridge’s pronouncements about the state of the world, she uses her institutional authority to silence him. She subjects him to torture in an effort to ensure he will change his testimony to fit the reality she has decided is suitable.

This provides a crucial object lesson in the questioning of authority. Dolores Umbridge has power given to her by the government and by the school at which Harry Potter lives for the majority of the year; there is no escaping her authority. There is no undermining it, either—at every turn, she collects more power over the lives of the students. But she is using her power to cause direct harm to those over whom she has authority, and she is doing so for the sole purpose of maintaining her access to said authority.

Power qua power. And thus, a revolution arises, for this is the lesson we learn from Dolores Umbridge: when one recognizes that following a person only increases that person’s ability to cause harm, it becomes one’s responsibility to resist.

There is one authority figure who it would be irresponsible to neglect, because he is the one who inspires us to question even the most seemingly legitimate of authorities.

Albus Dumbledore is a startlingly ambiguous character. He is rare in many ways: an adult who admits when he is wrong, a flawed leader who makes preventable mistakes, a chess master who forgets that people are not pawns, and who has cause to regret his machinations. He is nurturing, but dishonest. He is honest, but neglectful. He is the subject of heated canonical debate, as many characters ask themselves and each other: is this man deserving of the authority he holds?

As a character, Dumbledore does not provide tidy answers. He is arguably an instrument of good and an instrument of evil, and his development throughout the series does not provide clarity on the subject. An assessment of whether or not he is fit to lead requires constant attention—there is no place to rest. Even in his introduction, are invited to question him: he leaves a child in the care of a family who he knows will abuse him, neglect him, and suppress his growth—and his ostensible reasoning in that moment is that this upbringing will keep the child humble. We are invited to ask: does a man who makes this kind of choice deserve to hold the power to choose a child’s path?

Throughout the series, Dumbledore’s decisions unfold through the eyes of those impacted by them. He chooses to keep secrets and reveal information and make demands of those who follow him, and the question continue to arise: is he doing the right thing? And, if not, should he still be in charge?

The very fact this question is the subject of heated debate among readers speaks to the series’ successful education of a generation in the art of questioning authority. For—whether or not he ought to have been in charge—Dumbledore’s character demonstrates what is perhaps the most crucial lesson of them all, a lesson that is the refrain of another ambiguous character: constant vigilance.

It is never enough to decide an authority figure is Good or Bad. It is never enough to choose to trust someone once. It is never enough to see an initial demonstration of righteousness. No authority figure is beyond reproach, and no authority figure is truly deserving of unflinching, unquestioning obedience. Even when Harry Potter meets Dumbledore amid death itself, he continues to ask: are you worthy of being followed?

This, then, is the ultimate lesson we learn from Albus Dumbledore, and from every authority figure presented across the seven volumes of the Harry Potter series.

The lesson we must not forget, not even for a minute: Never stop questioning authority. Never rest in obedience. For the cost of rest is paid in blood, and the cost will always be much too high.

<>

My friend’s daughter was in the backseat of his car. He was driving, and dictating a text to me about Harry Potter and resistance. (Because that’s the sort of thing we text about.)

“What do you mean by ‘resistance’?” she asked him.

What followed, he later told me, was an intense conversation about authority.

And this, I told him, is how he knows he is indeed raising her to resist. She listens. She watches. And then she asks questions. She asks questions until she is satisfied with the answers, and then she decides if there are bigger questions that need to be asked.

Small questions: what do you mean when you say some authority is illegitimate? How can you tell when that’s the case? How will I know?

And then, bigger questions: when is the time to resist? What is the cost?

Finally, the biggest question of all: how will we fight?

Sarah Gailey is constantly asking questions.

All artwork by Jim Kay, from the Harry Potter illustrated editions, or found on Pottermore.