10 Authors Discuss Asexuality, Immigration, and More on December’s YA Open Mic

YA Open Mic is a monthly series in which YA authors share personal stories on topics of their choice. The aim of the series, above all, is to peel away the formality of bios and offer authors a platform to talk about something readers wouldn’t necessarily find on their websites. Check out previous posts here.

This month, our ten featured authors are discussing everything from motherhood to asexuality to immigration, and beyond. All of the authors have YA books releasing this December.

YA Open Mic runs on the first Thursday of each month.

***

Lauren Morrill, author of The Trouble with Destiny

The day I got “the call” that Meant to Be had sold was the last day of November. I always remember the date because our bank account was at $0. Well, I think we maybe had a few cents in there, but definitely no dollars. I wasn’t freaking out, because the following day was the first of the month, which meant pay day for both my husband and me. We were living in Boston and working entry-level jobs (me at a nonprofit, him at a public radio station), and so in an expensive city we were living paycheck to paycheck (mostly because we spent all our disposable income on student loans and eating out).

That night, I was supposed to go to a meeting for my roller derby league (at the time I was on the executive board of Boston Roller Derby), which was taking place in a bar. Which meant I probably needed to order something, and also leave a tip. That’s a problem when your bank balance has a zero in front of it. So I scrounged through my wallet and coat pockets and came up with two one dollar bills. A soda. That’s what I’d order. A soda for $1, and I could tip the other dollar. But that’s all. I was down to my last $2.

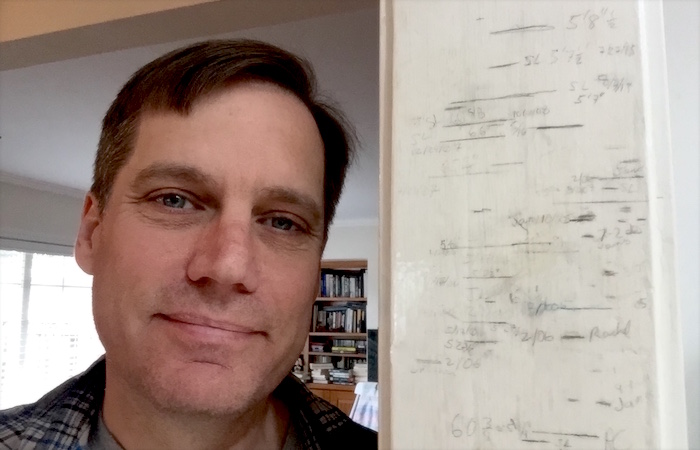

And then I got THE CALL. Random House (Delacorte Press, in particular) had made an offer on my debut novel. My life was about to change in a big way. And so, to mark the occasion, my husband snapped this blurry photo of me with our last $2, having just been offered a whole lot more dollars and the promise of fulfilling a lifelong dream.

Erica Cameron, author of Deadly Sweet Lies

I am asexual. It’s a fact of my life now, but it’s one I didn’t discover until I was 29 and trying to recover from an emotionally abusive and manipulative marriage.

I grew up in a liberal, diverse city in South Florida and the available spectrum of sexual orientations was always pretty clear: gay, bisexual, or straight. I could be attracted to anyone of any gender, and that was okay—it was something I knew both in theory and from watching my childhood best friend try to figure out her own sexuality as we grew up.

No one ever mentioned that being attracted to no one was an acceptable option.

Parents, teachers, and even friends told me over the years not to look for too much external validation. Or, at least to avoid letting that validation impact my self-worth. Sometimes, though, something has to be verified, labeled, and categorized by someone who isn’t in my head for my experiences and emotions to feel real and acceptable. That is especially true when the word I was looking for to describe myself didn’t exist in my vocabulary. Not outside the context of the short section in my freshman biology class about the asexual reproduction of amoebas, anyway.

It’s why I vacillate between the urge to laugh and cry when someone questions the need for diversity in books. I was a voracious reader as a child. How different would my life have been if I’d known at 9 or 19 what I discovered at 29 about the sexual identity spectrum? I won’t ever know the answer to that question, but I will try my hardest to be the voice that tells teen readers what I never heard. What I would absolutely love is for my asexual spectrum characters to provide the “Oh my god, that sounds like me” moment for at least one person. Not going to lie; it’s kind of a life goal.

Ingrid Sundberg, author of All We Left Behind

It was the summer of fire and I’d just turned 13. I was camping with my family and a man I barely knew asked me to walk down the river with him. We walked away from the voices of the campsite and sat on a log out of sight, with my bare feet in the water. “You’re beautiful,” the man said. “Can I kiss you?” I sat there, uncomfortable, sweat pouring off me from the heat and not looking at him. Hoping maybe, if I didn’t look at him, then he—and that question—would go away.

“No.” I didn’t look at him when I said it. I felt uncomfortable saying it, like I wasn’t allowed. He was an adult, and I’m supposed to respect adults. They’re supposed to be trustworthy. They’re not supposed to ask for a kiss. That one word is all I said. It’s all I needed to say. But what scares me is I continued to sit there in the silence after saying “no,” paralyzed and unsure if I’d said the right thing. I sat there waiting for permission from him. For him to tell me it was alright that I didn’t want his kiss.

We sat there for another ten minutes—in silence, with me refusing to look at him—before he got up and we walked back to the campsite and I never saw that man again. Nothing happened that day, yet everything happened. I learned what it is to not be seen as a child. I learned to avoid men. I learned that at 13 I look 16, but if I’d been 16 I know I would have done the exact same thing.

The very first scene I wrote for All We Left Behind is inspired by this experience. Only in my book the girl doesn’t say “no.” This story is very different when we’re too scared, and unsure, and looking for approval, that we say nothing. Girls are taught to be quiet. We’re taught to carry the silence.

Romina Russell, author of Wandering Star

My family immigrated to the United States from Argentina in 1990, when I was five years old. I felt like I had landed on an alien planet and was terrified for my first day of kindergarten, particularly since I didn’t speak a single word of English. I can still remember my terror mounting on the ride to school—How will I ask to use the bathroom?

It took all my concentration not to cry as I walked away from Mom—but the moment I entered the classroom, worry gave way to awe: Everywhere I looked, there were colorful paper hearts and chocolates and candies. My new classmates instantly welcomed me into their world of stickers, treats, and greeting cards. My parents were right: This was the American dream!

I came home in a delighted daze, carrying my cards and candy, gushing to Mom about how wonderful this new world was—how its people were so happy to have me among them that they threw a huge party in my honor!

She didn’t have the heart to explain that it was February 14th…Valentine’s Day.

Eric Lindstrom, author of Not If I See You First

When I was seven years old, I wanted to be a demolition derby driver. Over the years I considered all sorts of vocations, but two in particular came to mind and never left. One began in elementary school when I decided to be a writer, even if only part-time. The other came unexpectedly when I started high school and a family member came to live with us for a while. While she was at work, I babysat her newborn, but I wasn’t just keeping an eye on a baby in a bassinet; I was feeding, burping, rocking, changing diapers, and more. It amazed me to discover it was the best thing ever. That was how, at the age of 14, I decided that when I grew up I wanted to be a dad. Both of those dreams came true, and they are even better than I hoped or imagined.

Kate Jarvik Birch, author of Tarnished

There was a time when I wanted to own a flower shop. I was young and impulsive and I thought wanting something meant I should go right out and do it. I didn’t have a degree in business, never worked for a floral designer, but my mind was made up. With a bit of inheritance, I went out and leased a storefront; bought a huge walk-in refrigerator, a cash register, and every implement I could imagine I might need to run a flower shop. My store was called Morgan’s Gardens, named after my one-year-old daughter. I stocked it with daisies, roses, and lilies, every bright and beautiful thing.

But even though it was a cute store, with lovely arrangements, I don’t need to tell you that it failed. I lost all the money I invested into it. It was a rough time, rough on my pride, on my new little family. It hurt to fail. But like every other time I’ve failed, and there have been many (including five books I wrote that were never published), I ended up being grateful to the experience. The pain of failure taught me more than success ever could. It taught me to push through. It taught me to look for the positive even in the darkest times. It taught me what pain feels like, so that I can see it in others. It taught me a bit of what it means to be human so that hopefully I can write those emotions into the characters in my books.

Alexis Bass, author of What’s Broken Between Us

When I met Justin I was trying really hard to “be a writer.” I thought dating would be too difficult, given I didn’t have that much free time and was dedicating most of it to writing and revising and editing and querying and everything you do when you’re trying to enter the publishing game. “I don’t mind,” he said one evening when I left happy hour early, leaving him alone with a dish of half-eaten chips and spinach-artichoke dip, because I needed to finish a scene to meet my word count goal for the week and I knew it would take me all night if I didn’t start soon. “I meet a lot of people who are artists,” he told me casually. “Painters who haven’t painted in years; musicians who can’t find the time to perform or practice. You’re a writer, and you’re writing. I don’t mind.” Once he told his friends I was staying in on a Saturday night to write. I was embarrassed. I didn’t want people to see how much time and energy I was dedicating to something that could be considered a hobby, that hadn’t yet manifested into anything except personal rewards and satisfaction. But on some level everyone understands the need to create, the appeal of personal dedication, and that before the big dreams there lies the simple goal: don’t be a writer who doesn’t write.

Brigid Kemmerer, author of Thicker Than Water

A few months ago, I was watching a friend put on a paper bracelet at an event, and I said, “Here, I’ll do the mom thing and help you.” My oldest son, who has Asperger’s, frowned and said, “But you’re MY mom.” I explained to him that when you become a mother, in a way, you become a mother to everyone. I really believe that. Someone made a comment online recently—I know, I know, don’t read the comments—about how they’re sick of people “romanticizing” motherhood. I don’t know that there’s anything romantic about it, especially when I’m scrubbing vomit off the couch, but I do think there’s an understated power in the compassion and empathy that comes along with motherhood. Moms can change the world. We do it in quiet, meaningful ways, one person at a time. We do it in conversations and listening and treating scrapes and holding hands. There’s power in being a mother.

Now here. I’ve spent enough time talking. Come sit down so I can give you a hug and feed you some cookies. I want to hear everything about your day.

Estelle Laure, author of This Raging Light

When I was just about 14, my mother made me move to Taos, New Mexico. I was in a French school in San Francisco at the time, and after years of not fitting in, of being the new girl over and over, of being the little Buddhist girl in a town of Mormons or the only white girl in a school in Oakland, or being the one with the weird accent, or the one who wore dresses and sucked at gym, or the one who couldn’t afford the Guess jeans and the cabbage patch doll, I was finally among my own. None of them were athletic. They liked to listen to music and read and romp around the city from bus to bus like a pack of monkeys. “Mexico,” they all said. “Why are you moving to Mexico?” I finally got tired of explaining the convoluted mess that had led to our relocation and that New Mexico is a part of this country. Anyway, uprooting was nothing new. Mom liked to move around on a dime.

When I rolled into Taos on the Greyhound bus (I had been sent ahead of the rest because school was starting, but I also suspect my mom didn’t want to deal with my ‘tude while driving across multiple states) it lurched past the McDonald’s. Lowriders lined the parking lot, and just as I passed, a shirtless boy with a wicked, black, glossy mullet whipped a brush out of his pocket then spun it around and used the other end to douse his head in hairspray. Total trauma. I broke down, cried, banged my head on the window, shook my fist at the sky, at my mom, at life for its cruelty. So I can’t explain how I fell in love with the place the way I did. I still live there. The savage mountains, the sick sunsets, the brilliant creativity. What is it that makes Taos so magical is beyond me. I’m flummoxed every day as to why this place, of all of the places I lived, became home. The events that led me here are mysterious and if one tick of the clockwork had been different, I would never have known these people, had this life. So I guess the moral of the story is lowriders are amazing, but you can keep those creepy hairspray brushes!

Ally Carter, author of See How They Run

Sequels are hard.

This is a lesson I learned while writing the second Gallagher Girls book, Cross My Heart and Hope to Spy. I finished that book eventually and lived to tell the tale, hoping that I’d cracked the code and would never suffer from Sequel Syndrome ever again.

I was mistaken.

Embassy Row is a series I have wanted to write for ages, and Book One, All Fall Down, had an ending I loved because it set up some huge challenges for my heroine in the sequel. The problem, of course, was that then I had to write it.

As if writers aren’t neurotic enough, the deeper I got into the process, the harder the writing got. And soon those old questions started filling my head again.

What if the first twelve books were a fluke and I’m really not a writer?

What if my career is over?

What if I never sell another book again?

What if I’ve made my last dime in this business and I need to start hoarding money and food and compliments because the well is about to go completely, totally dry?

Needless to say, those questions don’t exactly help the writing process.

Then one day I got an email from a group of writer friends who were going to be in France for about a month and they wanted me to join them.

Oh, I can’t, I said. I’m writing the last book anyone will ever pay me for. I have to start dusting off my resume and changing my name. I can’t come to France.

Don’t you have thousands of frequent flyer miles? They asked.

Well…yes.

Come to France!

So I went to France.

It was one of the best decisions I ever made because 1. The Embassy Row series is set in a fictional country on the Mediterranean, and every morning I got up and went for a walk on the little curvy streets that overlooked the water and it was like I was in Adria.

But also 2. People don’t live in vacuums, so writing shouldn’t happen in one either. Being around friends and seeing amazing sites—eating amazing food—all of it just reminded me the world is much, much bigger than my office. It’s even bigger than my imagination. And that’s a beautiful thing.