11 Authors Discuss Dealing with Depression, Being Mixed Race, and More on September’s YA Open Mic

YA Open Mic is a monthly series in which YA authors share personal stories on topics of their choice. The aim of the series is to peel away the formality of bios and offer authors a platform to talk about something readers won’t necessarily find on their websites.

YA Open Mic is a monthly series in which YA authors share personal stories on topics of their choice. The aim of the series is to peel away the formality of bios and offer authors a platform to talk about something readers won’t necessarily find on their websites.

This month, 11 authors discuss everything from being mixed race to dealing with depression. All have YA books that release this month. Check out previous YA Open Mic posts here.

Kathleen Glasgow, author of Girl in Pieces

Much like Charlie Davis in my debut novel, Girl in Pieces, I had a hard time speaking up when I was kid. Charlie’s mom tells her, “No one’s interested, Charlotte.” When a parent tells you your thoughts and words don’t matter, you tend to believe them, and shut yourself down. No one’s interested.

The first time I saw the movie Inside Out, about the little girl who hides her emotions to please her parents, I cried. I cried the second and third times, too, and even the 56th time (my kids love that movie, if you can’t tell). Why is it we always tell our kids, “Oh, hush, don’t cry,” or “Stop that now, you’re overreacting”? Emotion is spectacularly human—it’s the most beautiful part of being alive: the rush of roller-coaster feelings you get when something bad, scary, or wonderful happens.

I recently reread my high school journals. Here’s a direct quote: “I have been suppressing my feelings my whole life. Now they are starting to come out.” They didn’t come out in healthy ways, like talking. They came out in self-destructive ways, through drugs, through cutting, until I learned to speak. And say, “I want.” Or, “I need.” Or, “I love.”

I try as hard as I can to let my kids express themselves, to let them know any emotion they feel is okay and normal. Even when they don’t know how to put their feelings into words, they can use other ways: drawing, running around the yard, breathing deeply. Crying.

My 3-year-old daughter had a rough morning the other day. Nothing fit: her dinosaurs kept falling down, the dog ate her cream-cheese cracker. But we talked, and she calmed down. I said, “How do you feel now?”

She pointed to a tall flower in the yard. “I feel sunflower.”

Me, too, kid. Me, too.

Rafi Mittlefehldt, author of It Looks Like This

I didn’t yet know how to be myself in high school. The me I was on any given day belonged to anyone else, everyone else. It was the me I thought I was supposed to be.

I walked into first period one morning senior year just as a classmate, Luis, was telling another, Noah, he was gay. This wasn’t some grand announcement. Luis said it matter-of-factly, pretending it was common knowledge.

Noah knew he was gullible by nature and suspected a prank. So when he asked me if it was true, I played along.

“Yeah, Noah. Everyone knows.”

That sealed it. I sat down and waited for the punchline, but it never came. And when I studied Luis’s face, and then everyone else’s, I realized this wasn’t a joke.

It was a transformative moment. This was the first out kid I knew. There was so much I wanted to ask him…but I wasn’t ready. I came out the next year, in college, and started the long process of being the me I wanted to be.

Twelve years later, I found Luis on Facebook. On a whim, I sent him a message, telling him I’d always admired his courage and wished I’d had the same. His response was warm and cheerful and stunning: shortly after high school, he decided not to be gay anymore. “I just know what God wanted of me.”

It was so disheartening. For the last decade, while I had grown comfortable in my own skin, Luis had gone backward.

I still think about him. Sometimes people get so used to their own environment, they think everyone else has it as easy; that how far we’ve come means most of the work is done. Sometimes well-meaning allies tell me that stories about coming out and homophobia feel dated now.

When they do, I think of Luis.

Kristen Simmons, author of Metaltown

I am half Japanese. Mixed. Hapa haole (half Caucasian) as my mom calls me.

When I was younger, I looked full Japanese, but as I started to get older the way I looked became harder to place. By the time I was in middle school, people regularly assumed I was Hispanic. I didn’t always correct them. There were not many Asian kids where I grew up.

Well. Half-Asian.

It’s a strange thing, being half something. Is it good? Bad? Is the glass half full or half empty? I do not speak Japanese, nor do I observe Japanese customs—apart from eating white rice with everything, I was not raised with any. Assimilation was the goal, for my mother first, and then for me.

Don’t stick out. Don’t be different.

But sometimes people really want me to be different.

It started in high school. Jokes about math (which I am terrible at), driving (which I’m decent at), and computers (I still have an AOL account, does that tell you anything?). Then college. I started marking Asian/Pacific Islander on forms, but it felt strange, because there was no “Mixed” box. No “Half Japanese,” box.

It got even better after college. A coworker brought me a statue of the Iwo Jima Memorial because it included “both of our people.” Another bowed to me after bringing a box of supplies, and said thank you in Korean. The best was when I, the only Asian person at my job, was honored at Asian/Pacific Islander Month with a potluck lunch. People brought teriyaki noodles and instant rice. I was asked to wear a kimono. I do not have a kimono.

Regardless of where people want to place me, I still don’t feel comfortable marking the race box, even now in my thirties. It’s not just because I’m half; it’s because I’m somewhere in between. My culture is blended, individualized, unable to be confined to a box. Some days I like it that way. Some days I’m not quite sure who I am.

C.B. Lee, author of Not Your Sidekick

For the longest time I was ashamed about having major depression. My parents, immigrants from China and Vietnam, struggled their whole lives to build a better future in a new world. They had high expectations, especially about what defined success: a good job, a stable home, strong relationships.

In high school, the pressure led to a huge shutdown my senior year. The overwhelming college application process and the fear of failure led to a major depressive spiral and suicidal ideation. This would follow me throughout college and my later career pursuits. While my parents were supportive of me, they didn’t know how to deal with it at first.

The concept of “saving face” is tied a lot to how we would not acknowledge our emotions; it was how my parents were raised and how they raised me. As I started medication, therapy, group therapy, I still felt ashamed. Ashamed of my mind, ashamed that I had burdened my family in this way, ashamed that I had failed as a child to take advantage of this opportunity for a good life that my parents had worked so hard for.

There is a widespread stigma around depression and other mental illnesses where we don’t acknowledge the importance of mental health, where we are afraid to talk about it, especially in Asian American communities when it’s difficult to communicate that emotional need across the generational and cultural gap.

It took time and patience for me to let go of shame. Depression is normal; it can happen to anyone. Today I can talk openly to others about my mental illness, to communicate with my loved ones about what I need and how I’m feeling. I’ve defined my own success pursuing creative work, and encourage people everywhere to define their own success.

Rae Carson, author of Like a River Glorious

When I was ten years old, I almost died. A lot.

Once, it was because Danny, our seedy apartment complex’s resident bully, pulled a knife and pressed the blade to my throat. “I could kill you right now,” he said.

“Yes,” I acknowledged solemnly. “You could.”

He decided not to. Maybe he never intended harm in the first place, but he was so jacked up on drugs that how could I know? It was not the last time he pulled a knife on me.

That same year, I got sick after a family lake trip. I’ll spare you the gory bowel details. Suffice it to say that after a couple of weeks, I was skeletal, with skin like rancid milk.

My uncle had just been diagnosed with giardia, which was a windfall of luck because we could tell the doctor, “Please skip all the expensive basics and just test for this.” The treatment saved my life.

Later that year, when money was even tighter, I got pneumonia. After two weeks it had spread to both lungs, and I was nearly comatose.

My aunt’s family doctor agreed to meet me off the books at his clinic in the middle of the night. Mom rushed me out the door and bundled me up in our beater Pinto. The car finally gave up the ghost and refused to start. I remember Mom pounding on the steering wheel in panic and frustration, tears streaming down her face.

We borrowed a neighbor’s car, made it to the doctor, got a couple shots of antibiotics, and two days later I knew I was going to live.

Poverty kills, and when it doesn’t, its effects can last a lifetime. I have nightmares about being hungry. The slightest sniffle makes me contemplate mortality. I startle if large men like Danny get too close.

My first book series for teens starred a protagonist who grew up with wealth and opportunity. But lately, I’ve finally felt healed enough to write about people who have a whole lot less. The Gold Seer Trilogy is a step in that direction, and poverty is a topic I expect to explore a lot more in the future.

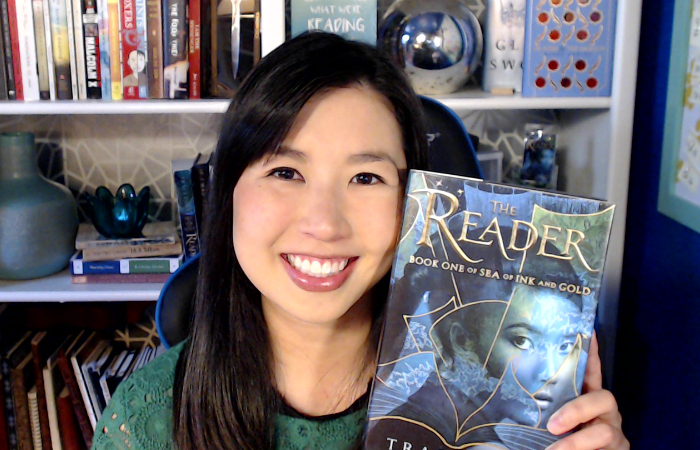

Traci Chee, author of The Reader

When I was fifteen, my grandfather died. Cancer. He’d been sick for a while.

It was near the end of the school year, during standardized testing week, so my days were all No. 2 pencils and Scantron sheets. I’d gotten through a slew of exams that morning and was just sitting down to lunch with my friends when my mom sent me a note through the school office.

Get a ride home today.

And I knew. I knew.

But I had to hear it. So I dug up thirty-five cents, called my mom on the payphone by the girl’s bathroom, and she told me what I already knew.

My grandpa was dead.

I remember crying so hard I couldn’t sit through the rest of the lunch period with my friends. But I couldn’t go home either. I had tests to finish.

So I went back to the classroom, where two male teachers were chatting as they waited for the bell to ring.

When they saw me crying, one of them muttered, “Must be a boy.”

The other nodded sagely. Or chuckled. He certainly didn’t ask me what was actually wrong.

And at that moment I wasn’t sad anymore. I was angry. I looked up and said in the coldest voice I could muster, “My grandfather just died.”

They shifted uncomfortably. Good. They should be uncomfortable. I was mourning my grandpa, and they thought because I was a girl, my tears were for some unrequited love or sordid breakup or whatever other sexist garbage they tried to pin on me.

The bell rang. I finished my tests. I attended my grandfather’s funeral that weekend.

Life doesn’t wait in line to come at you, I think. There are exams to take, deaths to mourn, and sexism to shut down when you see it. And it’s hard. And sometimes you cry. And that’s okay. It’s a lot.

But you can do it.

Paula Garner, author of Phantom Limbs

When I was in fourth grade, a new girl in school became my best friend. Kim was the funniest person I had ever met, and I needed those laughs; my life at home was not the happiest. We would walk home from school together and stand on the corner where our paths diverted, unable to part ways because we simply could not stop goofing around and laughing.

One night, Kim invited some friends for a sleepover. In the middle of the night, we were awakened by raised voices in the living room—then terrible crashing, then screaming, then sobbing. We were frozen with terror. Kim didn’t say a word. It occurred to me that maybe this was not the first time something like this had happened in her house. If that was the case, she’d never told me.

In the morning, Kim’s mother’s arm was in a cast. She feigned cheerfulness as she made us breakfast, making up a story about her arm, as if it were possible we hadn’t heard the violence.

Shortly after that, Kim disappeared. At school, I learned that she had moved away. I never saw or heard from her again. To this day, thirty-some years later, I still wonder about her.

Phantom Limbs was, in part, an examination of relationships that are severed without closure, leaving one confused, lost, even haunted. When Otis loses Meg, his best friend (and first love) who moves away abruptly and seemingly without a backward glance, he is heartbroken and confused. But three years later, they meet again, and Otis finally has a chance to get answers.

I wanted to reunite Otis and Meg to allow them a chance to work out what happened in the past—and in so doing, give them an opportunity some of us never have.

Sara Raasch, author of Frost Like Night

One of the biggest (if not the biggest) emotional themes in the Snow Like Ashes trilogy is the idea of being enough. I tell people this whenever they ask what I most hope readers take away from the books: that they come away knowing they are enough on their own, without outside influences or magic or anything. The inevitable follow up question is always, then, “Where did this theme come from?” and I’ll say something innocuous like “My own insecurities” or “Doesn’t everyone feel they aren’t enough at some point?”

But I know exactly where this theme came from, and talking about it in public forums is something I to this day find difficult.

“It” is my very heavily religious upbringing. I grew up Evangelical Christian, which isn’t unusual in America, but the sect I was involved with was of the far more aggressive, dependent sort. My response to the “Where did this theme of being enough come from?” question is far more complex than I will ever be able to admit in a public light—not because I’m afraid I’ll offend someone or I don’t want to discuss taboo topics, but because I know how desperately important it was to me once, and I would never want to take that support away from someone before they were ready.

So I weave themes of being enough on your own into my books, in case someone is ready. Maybe they’ll find it. Maybe they won’t. But it’s there, much like the truth: you are enough, on your own, whether you know it or not.

Kendare Blake, author of Three Dark Crowns

When I was in middle school I thought I would work on Wall Street. I didn’t have much of an idea of what working on Wall Street entailed at that age, besides putting gel in my hair and rocking a suit and being real intense like the dudes in that Michael Douglas movie, but it seemed a worthy goal, both exciting and safe, like I could have days of nail-biting over precarious deals yet still feel secure about making a living. Looking back, I don’t know why I thought that, but there you go.

Of course, I was also reading. Stephen King, Anne Rice, Poppy Z. Brite, Maeve Binchy, Charlotte Brontë, anything I could get my hands on. And by that time I’d tried my hand at writing a novel. It was a crap novel, though, just a challenge to myself to see if I could.

I enjoyed writing. Always had. Every written assignment in school, every word problem was a bit of a thrill. I mean, math was fine, there’s something comforting about rules and a right answer, but an inch allowed for creativity was worth its weight in gold in those days full of worksheets and multiple choice quizzes. If the answer could be written in words, I would find a way to insert my voice into it. I would find a way to smart off. For the most part, teachers tolerated it. I think I thought they might enjoy it: a break in the tedium of one-word answers. I was a considerate little smartass, you see. But if they appreciated my efforts, they made no note of it. Except for one. My earth science teacher, Mr. Kosel.

“Hey, not bad,” he commented on a paper about environmental conditions on Venus that I had turned into alien evolution fiction. “Ever think about becoming a writer?”

I had. But it had never seemed possible.

Still didn’t, and I stuffed that idea down deep and went to college to study investment banking. But I’m not an investment banker. I’m a writer. And I remember that written note, on that assignment about Venus, more than ten years later. So thanks, Mr. Kosel, for the encouragement. Also, thanks for not marking me tardy for an entire quarter even though I SO was. And while we’re at it, I’m sorry about that time years later when I busted into your classroom during non-school hours and doodled on your pristine whiteboard. I hope it didn’t take long to erase.

Zoraida Córdova, author of Labyrinth Lost

“You should write the story of your own life,” he said. It’s usually some guy at some party somewhere in Manhattan. I rarely like to tell strangers I’m a writer because they want to know too much. When you’re an artist, people feel entitled to the intimate details of your life. How much do you make? Are your books selling well? Are you a New York Times Bestseller? Why don’t you write about this, this, and this?

I get it. Professional authors have eschewed traditional business to follow their dreams. Honestly, different writers write for different reasons. Some outsiders admire that. Others are baffled by how we pay our rent. It’s the literary equivalent of staring at a blue splatter paint canvas at the MOMA and saying, “Oh, I can do that, too.”

After I awkwardly talk around the first couple of questions, I answer suggestions to write about my life with, “I’d rather write fantasy.” For me, fantasy isn’t just mermaids and other realms. It’s also happy endings and grand gestures in romance novels. It’s aligning serendipitous moments in order to create True Love. It’s setting rules for fiction that wouldn’t be believable in the real world.

My life has been pretty ordinary. I grew up in a working-class, single-parent home. I was painfully quiet and shy up until I was 18. I’ve had boring retail jobs and chaotic nightlife jobs. I write fiction because I want to heighten the ordinary and create something new. My characters already have little parts of me.

For now, I’ll just stay making things up and keep this motto close to my heart: don’t quit your daydream.

Kerri Maniscalco, author of Stalking Jack the Ripper

In my mid-twenties I learned that sometimes things have to break before they can come back stronger. All at once, I lost my job and my apartment. I’d gotten out of an emotionally abusive relationship. And I had to move back home. Broken and defeated. I felt like every piece of me failed at being an adult and I had no idea how to fix it.

I was embarrassed and depressed and wanted to hide from the world, fearing that everyone would see the truth: I was a failure and a loser. Writing and reading were always my go-to’s when I needed to vent or feel whole again. So while searching for new jobs, that’s precisely what I started doing. I’d read and write until my veins practically ran with ink and my mind swam with possibility.

It wasn’t a magic cure-all, but it certainly stitched me together. With each new adventure I emerged stronger. More willing to fight for what I believed in. For who I was. For this wild dream slowly taking shape. I wanted to be like my favorite heroine and do the impossible thing—I wanted to be a published author. I’d never let myself believe that could happen before.

Without all of those doors slamming at once, I wouldn’t have been pushed into trying to make a living doing something I love. Like the best books prove time and again, plot twists force growth. I could look at all the ways I had failed, or I could start writing my own story. I could slay my own dragons.

Now when I look back on that dark time I see cracks of light streaming through the fissures. The darkness helped me find that speck of hope and follow it to this whole new chapter, one where I’m writing a series of my own to share with readers and dreamers like me. Once upon a bleak time, it’s something I never dared to imagine could be real.