"The Shock of his Bad Behavior": Claire Tomalin on Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens, observes Claire Tomalin in her recent life of the writer, “saw the world more vividly than other people…. He stored up his experiences and reactions as raw material to transform and use in his novels and was so charged with imaginative energy that he rendered nineteenth-century England crackling…” And the author who towers over almost all other novelists of the Victorian era not only burned with furious intensity on the page, but in the real world as well: “[W]herever he went he produced what, much later, an observant girl described as ‘a sort of brilliance in the room, mysteriously dominant, and formless. I remember how everyone lighted up when he entered.'”

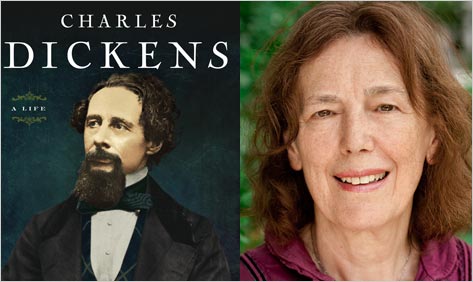

Tomalin first chronicled the dark side of that Dickens’ solar personality more than a decade ago, in her book The Invisible Woman, which challenged much of the conventional wisdom about the writer’s secretive late-in-life romance with actress Nelly Ternan. With Charles Dickens: A Life, she has brought into focus the man who called himself “The Inimitable”, from childhood to the pinnacle of literary success — and lends form to the mysteries that surround his final days.

As we approach the 200th anniversary of Dickens birth (on February 7), we asked Claire Tomalin to share some of her thoughts about the man in full. In an email conversation with the Barnes & Noble Review, the author spoke with us about Dickens, the art of biography, and the special connection between biographer and subject.–Bill Tipper

The Barnes & Noble Review: You open the book with a scene reconstructed from an experience Dickens had as part of a coroner’s jury, when he was a still-young novelist. Although you give us the scene in a style of your own rather than as Dickens himself, there is something instantly recognizable in the vision of the world — a crowded scene of everyday tragedy, but with an almost comic sensibility emerging at points in the details. The juxtaposition of light and dark –both in his writing and in his emotional life – is a theme you return to several times in this book.

Claire Tomalin: What I intended in starting the book as I did was to present Dickens, adult, in 1840, in the flush of his success, as he appeared to his friends. I’ve always been fascinated by this small episode, which is documented in The Times as well as in Dickens’s own writings. It so perfectly encapsulates his particular concern with the lowest people in English society – working girls, often workhouse born, nameless, without family or support of any kind. Just such as one is ‘the Marchioness’ in The Old Curiosity Shop, which he was about to write – a little slavey literally enslaved, half starved and doing all the work of the household, and held prisoner in her employers’ basement in her case. In his last finished novel he drew another bottom-of-the-heap child worker in ‘Jenny Wren’ [or Fanny Cleaver], severely physically handicapped, motherless, with an alcoholic father, but who nevertheless thinks up a way of earning her living by making dolls’ clothes.

Only when I started to look into this did I realize that the workhouse where Dickens went as juror was just a few streets west of the grand house he had just moved into in Devonshire Terrace, south of Regent’s Park. A map of London in the 19th century is a very useful adjunct to Dickens studies: the workhouse dated back to the previous century, when that was open ground, and had simply grown and grown over the years.

You are right in seeing how, in describing the preliminaries to the inquest, Dickens could not resist making a gruesome joke about the dead baby. Dead babies were quite often joked about in his work.

BNR: When you wrote your biography of Jane Austen, you remarked on the apparent contrast between her life – which had been thought by most critics and biographers to have run “quietly and smoothly” — and that of a writer like Dickens, whose life story comprises a drama containing incidents almost as famous as those in his stories. Of course, your treatment of Austen’s life found it hardly uneventful. But moving to Dickens must have been a tremendous change, if only in the sheer quantity of documentation by the writer and his contemporaries. How different was it to approach his life?

CT: With Jane Austen the biggest challenge was reading the critical studies. You’re right, that the mountain of material about Dickens, biographical and critical, is worse than any of the dust heaps in Our Mutual Friend – and quite as valuable. John Forster, Dickens’s closest friend and appointed biographer, early critic, corrector of proofs, adviser, confidant trusted with all his secrets, was my constant guide – I’ve always believed his work to be one of the great 19th century biographies. Of course there were things he could not write about, but his portrait of Dickens in wonderfully true and human.

I’ve had many years to read and re-read critics and commentators – Gissing, Chesterton, Angus Wilson, the Leavises, Humphry House, Edmund Wilson, Philip Collins, John Carey, Rosemary Bodenheimer, John Bowen and many more – no forgetting the indispensable and great Robert Patten’s book on Dickens and his Publishers. You have to take in as much as you can and use it as best you can. At the same time you are primarily nourished by Dickens’s own letters and writings. So it is a large undertaking.

BNR: You write of the childhood genesis of his early nom-de-plume, ‘Boz’ and write “Dickens liked to keep hold of every part of his life, and relate each to the others.” Do you see that as the impulse that drives the moral vision of the books, as well – the notion of a world where the connections between high — and low, rich and poor, chaotic market and stately table are always in danger of being ignored, or denied?

CT: Rather, I think Dickens nourished his imagination by constantly refreshing his memories. Think of him writing Little Dorrit in the mid-1850s and going back to the 1820s when his father was in the Marshalsea and he was a child, like Little Dorrit — only not like her at all, of course, since he was full of indignation and shame and intent on preserving his own integrity when John Dickens was in the Marshalsea. But you are right too about the moral vision of his books, which always insisted that we are all tied together, the lowest and highest in society, and that no man is an island — something we need reminding of regularly.

BNR: One of the most illuminating portions of the book deals with Dickens’ founding with Miss Coutts of the “Home” in Shepherd’s Bush. He was not only putting his money where his mouth was when it came to reform, but it seems to me that he avoids quite a bit of the pitfalls other Victorian schemes of this sort fell into. His resistance to overbearing religiosity is striking. Where in your opinion did it come from?

CT: I’m glad you like the chapter about the Home for Homeless Women. I became interested in it when I was researching my earlier book, The Invisible Woman, and learnt more about it from Jenny Hartley’s excellent book Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women. You are right that he was insistent that the young women should be shown that life could be good, given pretty clothes, comfortable beds, little gardens to tend, music, books – and not preached at and told they were wicked. Similarly, when he visited a ragged school, where street children, in and out of prison, where given rudimentary education, he said the first thing they needed was somewhere to wash – they were all filthy – rather than being told about Jesus and God, who could mean nothing to them. Dickens was very practical and sensible. He did not expect all the girls in the Home to change their ways, but he did make it work for some.

BNR: You take an approach here sometimes that suggests you see Dickens as a sort of a friend, and when he behaves badly, you’re not afraid to say that you’re ashamed of him. “You want to avert your eyes from a good deal of what happened during the next year, 1858.” I think this expresses – in a manner a biographer doesn’t often give voice to – the complex but still in many ways fervent feelings of admiration we have about the man, and our sense of disappointment when he doesn’t live up to that ideal. When you first began researching his life for The Invisible Woman, did you experience that?

CT: I did find writing about the events of 1858 and the marital breakup very painful. When you live with Dickens for years, reading him and trying to present him as faithfully as you can, you can’t fail to love the man – so the shock of his bad behaviour is considerable, even when you know it is coming. When I wrote The Invisible Woman I was telling Nelly’s story, so it was rather different — and I was so caught up with the thrill of tracing her history, early and late — it is an amazing one — that I let Dickens remain the minor character. I didn’t have to worry too much about his behaviour. Of course Nelly learnt from him how to deceive and lie effectively.

BNR: Is affection for her subject necessary for the biographer? Or is it an impediment?

CT: It’s an odd situation: I could not write about someone for whom I felt no affection or admiration. [Although I understand the interest of writing about real villains, Hitler, Stalin.] As I have grown older I have come to feel that it’s no good scolding your subject, rather you must be tolerant of bad behaviour. It is part of the human picture and we are all sometimes badly behaved, we all have something we are ashamed of, don’t we? I have been fascinated by Dickens worshippers who strenuously deny that he did anything wrong in relation to his wife, even though the record is clear that he did. They say, well there is no proof that Nelly was his mistress, to which I reply, that’s not the point – we know he wrote a lying letter to Miss Coutts about Catherine not loving her own children. We know he neither wrote to her nor visited her when the news came of Walter’s death. We know he did not invite her to Katey’s wedding. And so on.

I don’t think affection is an impediment, but I think one should avoid sentimentality.

-January, 2012