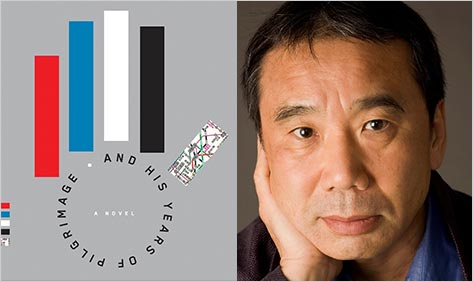

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

If you’ve never read Haruki Murakami before, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, which sold more than a million copies during its first week on sale in Japan, isn’t a bad introduction. With its focus on mutating, amorphous friendships and the sometimes blurred lines between dreams and reality, this deceptively simple tale of a solitary, self-effacing man’s search for connection and meaning in his life is more like the perennial Nobel contender’s earlier novels — including Norwegian Wood, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, and my favorite, Kafka on the Shore — than his most recent doorstop, 1Q84, a complex detective story that featured alternate realities and parallel worlds. Colorless Tsukuru is a wonderfully accessible choice for book groups because it wears its profundity lightly.

If you’ve never read Haruki Murakami before, Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, which sold more than a million copies during its first week on sale in Japan, isn’t a bad introduction. With its focus on mutating, amorphous friendships and the sometimes blurred lines between dreams and reality, this deceptively simple tale of a solitary, self-effacing man’s search for connection and meaning in his life is more like the perennial Nobel contender’s earlier novels — including Norwegian Wood, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, and my favorite, Kafka on the Shore — than his most recent doorstop, 1Q84, a complex detective story that featured alternate realities and parallel worlds. Colorless Tsukuru is a wonderfully accessible choice for book groups because it wears its profundity lightly.

Tsukuru Tazaki is an uncommonly sympathetic character, as steady as a surgeon’s hand, as trustworthy as a pencil. He’s forthright about his sorrows, but he’s not a whiner. When Tsukuru’s tight-knit group of high school friends — two men and two women — categorically cut him off without explanation during his sophomore year in college, his self-esteem takes a nosedive, sending him into a suicidal depression for months. “Alienation and loneliness became a cable that stretched hundreds of miles long, pulled to the breaking point by a gigantic winch,” Murakami writes.

Tsukuru recovers his equilibrium, but the experience changes him permanently: “The pain of having been so openly rejected was always with him. But now, like the tide, it ebbed and flowed.” He settles into a “small and lonely” life in Tokyo: cooking his meals, swimming his daily laps, drinking his half bottles of beer (all he can tolerate), and showing up for work. Murakami explains, “Habit, in fact, was what propelled his life forward. Though he no longer believed in a perfect community, nor felt the warmth of chemistry between people.”

Tsukuru has no clue why his friends have banished him — and he’s too shattered to press the issue — but that doesn’t stop him from conjecturing. Could it be because he’s the only one who left their hometown of Nagoya for college? Or because “there was not one single quality he possessed that was worth bragging about or showing off to others. At least that was how he viewed himself. Everything about him was middling, pallid, lacking in color.” After the shutout, he regards himself as “an empty vessel. A colorless background,” bringing too little to relationships to sustain them. But Murakami easily sustains our interest in this low-key but deeply drawn character, who comes across with seductive limpidity in Philip Gabriel’s admirably nuanced translation.

Murakami hits the color theme hard — a fine starting point for book group discussions. Everyone in the group except Tsukuru has names that contain a color. Interestingly, while Tsukuru’s male buddies’ names evoke red and blue — bright primary colors — the two women, each a source of suppressed romantic involvement, are linked to monochrome shades of black and white. So, too, is Haida, Tsukuru’s only friend in Tokyo — a philosopher, music lover, and fellow swimmer at the university pool — whose name means “gray field.” As with the two women from Tsukuru’s high school circle, there’s also a suggestion of sexual tension between Tsukuru and Haida — though it is possibly all in Tsukuru’s head, either imagined or dreamed, and in any event, never discussed.

Murakami hits the color theme hard — a fine starting point for book group discussions. Everyone in the group except Tsukuru has names that contain a color. Interestingly, while Tsukuru’s male buddies’ names evoke red and blue — bright primary colors — the two women, each a source of suppressed romantic involvement, are linked to monochrome shades of black and white. So, too, is Haida, Tsukuru’s only friend in Tokyo — a philosopher, music lover, and fellow swimmer at the university pool — whose name means “gray field.” As with the two women from Tsukuru’s high school circle, there’s also a suggestion of sexual tension between Tsukuru and Haida — though it is possibly all in Tsukuru’s head, either imagined or dreamed, and in any event, never discussed.

Tsukuru’s name, chosen by his father, a successful businessman in real estate, means “builder” — appropriate for a man who, following his lifelong fascination with train stations, becomes an engineer who designs them. The web of railroad lines spread over Tokyo not only supplies the image for Chip Kidd’s striking cover design but an overarching metaphor for how people connect, travel along parallel paths for a stretch, and peel off in different directions, sometimes converging again at a station farther along life’s tracks, sometimes missing their stops or connections. Murakami’s narrative suggests that the more stations you build — “The kind of station where trains want to stop, even if they have no reason to do so,” the greater the likelihood that people will intersect.

Colorless Tsukuru is a quest novel about Tsukuru’s journey at thirty-six toward confronting what his new girlfriend calls “unresolved emotional issues.” Sara Kimoto, who, not coincidentally, also works in the transportation industry — for a travel agency — is an oddly charmless character, coolly efficient to the point of detachment. On their fourth date, she essentially issues an ultimatum: Find out what really happened sixteen years earlier with his friends and stop living like “a refugee from his own life” — or sayonara. The wonder is that Tsukuru doesn’t switch trains, yet Murakami certainly makes us feel his relief at his newfound ability to experience overpowering desire.

As in Murakami’s earlier work, music plays a central role. At one point, he compares our lives to “a complex musical score . . . Filled with all sorts of cryptic writing, sixteenth and thirty-second notes and other strange signs.” The “Years of Pilgrimage” in the title refers to Franz Liszt’s mid-nineteenth-century set of three suites for solo piano — which in turn refers to the Romantic literature of self-realization, including works by Goethe and Byron. The haunting section titled “Le mal du pays” (homesickness), which occurs late in the first suite, recurs like a leitmotif through Colorless Tsukuru, perfectly capturing the subdued mood of the novel and its theme of yearning for lost innocence. It is a piece that Tsukuru’s high school crush, Shiro — graceful, serious and ultimately disturbed — played beautifully, and that Haida later plays on Tsukuru’s stereo, eventually giving him the boxed set of Lazar Berman’s ethereal recording. (You can find it on YouTube here.)

I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that there’s a sentimental as well as Romantic-with-a-capital-R aspect to this novel, and some classic Murakami bizarre sidebars, including a long discourse on hyperdactyls, people with six fingers. In fact, it’s a difficult book to quote, because out of context, much of the dialogue, especially, sounds either flat or trite: “I’m fond of you, too, very much,” Sara responds pallidly at a key moment.

Murakami fans who love his mix of the hyper-real with the occasional dash of the dreamlike might also want to check out Alessandro Baricco’s wryly amusing, beguilingly strange pair of interconnected novellas, Mr. Gwyn — which also centers on alienation and music, though with a more determinedly surreal spin — and, coincidentally, also features a gorgeous cover design and appealing small-format hardcover edition. Both Colorless Tsukuru and Mr. Gwyn encourage us to follow their solitary protagonists down intricately branching, often mysterious tracks that lead to surprising destinations — the kind of journey the best books offer.