Coming Home, Again, to Ursula K. Le Guin

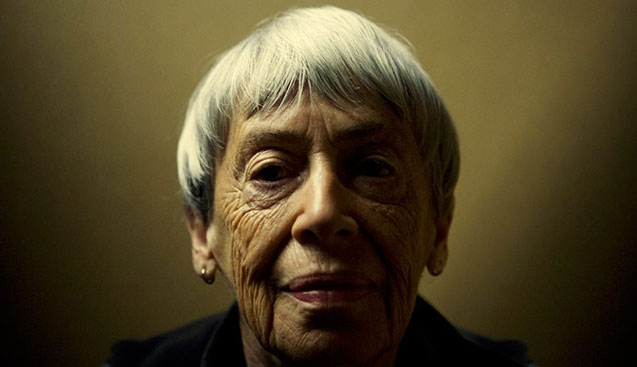

I’ve long referred to Ursula K. Le Guin my literary grandmother, a polestar of my understanding of fiction, fantasy, and the world itself. When I learned yesterday that she had died, even if at the respectable age of 88, I sat down and cried. I cried long, wracking tears, the kind that make me feel wrung out and made of salt, desiccated and thin. She is the writer I found at that specific age when I wasn’t so young that I barnacled and burnished her fiction with the obscuring mist of nostalgia, nor was I too weary and worldly to be above young adult fiction like A Wizard of Earthsea. Indeed, her work has kept me from succumbing to the fallacy that I will ever be too important to read books about that terrifying time between childhood and the adult world.

I’ve long referred to Ursula K. Le Guin my literary grandmother, a polestar of my understanding of fiction, fantasy, and the world itself. When I learned yesterday that she had died, even if at the respectable age of 88, I sat down and cried. I cried long, wracking tears, the kind that make me feel wrung out and made of salt, desiccated and thin. She is the writer I found at that specific age when I wasn’t so young that I barnacled and burnished her fiction with the obscuring mist of nostalgia, nor was I too weary and worldly to be above young adult fiction like A Wizard of Earthsea. Indeed, her work has kept me from succumbing to the fallacy that I will ever be too important to read books about that terrifying time between childhood and the adult world.

There are going to be a lot of retrospectives of Le Guin’s work this week, this month, and they will be filled with the well-deserved superlatives about her career as a science fiction and fantasy writer: she won this award, she broke that boundary. She began writing in a strange period, before genre fiction could be considered literary, and when women who wrote it were not exactly standard. Some of her early books feel antique to modern eyes. In The Left Hand of Darkness, Genly Ai cannot help but think of the ungendered denizens of an alien world as “he,” a standard pronoun only just visibly exploded in the Nebula-winning Ancillary Justice, written 40-odd years later.

Yet she also cut paths other writers haven’t yet followed into the dark deep. The breadth of Le Guin’s body of work is staggering: science fiction and fantasy, literary fiction, poetry, criticism, short stories, translations, children’s books, and so much more. One can easily understand why she struggled with and rejected the label of “science fiction writer,” even as she helped redefine what was possible in the genre.

My first blush with Le Guin was A Wizard of Earthsea, undertaken while I was away on a semester in London, a continent and a culture removed from my home in the American Midwest. (Old joke by George Bernard Shaw: England and America are two nations divided by a common language.) I was invigorated, homesick, lovelorn, and adventuresome, halfway through my 20s and drunk on life and lager. I can’t remember how this young adult novel came into my hands—this compact telling of a young magician’s rise to his inevitable and unenviable power—but it did, happily. Either despite or because of my strange circumstances—on the fraying edge of my college years, set loose on a beautiful and incalculable city, both carefree and careworn—A Wizard of Earthsea absolutely slayed me, and set me reading everything she put to page. Inevitably, inexorably, my relationship with Le Guin has been the longest, loveliest literary romance of my life.

I never read her books in a comprehensive way, though I did tend to move through a series in something like a chronological manner. The Earthsea novels—the first three written in the ’60s, and the latter ones in the ’90s—hew to something like a timeline, one book in front of the other like a path, but that series may be the only one that approaches anything resembling linearity. And even then—the Earthsea of the first trilogy is a different place than the later three books, written 30 years later, when Le Guin was a different writer. Her works tend to loop and fold onto themselves, more beholden to emotional reality than adherence to false exactitude. The world of Werel (featured in the stories of the Hainish Cycle) shows up again and again, and every time we encounter its people, they too have changed and grown.

Le Guin coined the term “ansible” in her very first published novel, Rocannon’s World (a deliriously wonderful mess for the completist: in 200-odd pages it details five alien species, at least two human cultures, and cats with wings). An ansible is, of course, a device that can violate the relativistic prohibition against reciprocal communication. In other words: people light years away from one another can communicate instantaneously across the emptiness, while their physical bodies must move more slowly across the void, bound by Einsteinian physics. In other, other words: in Le Guin’s Hainish novels, shaped and bound by this complexly simple technology, information and communication moves as quick as thought, but it takes a while (decades, centuries) for our bodies to catch up.

In her introduction to The Complete Orsinia, Le Guin writes that “True journey is return,” a theme found in much of her work. In The Left Hand of Darkness, Genly Ai, of the loose confederation of ansible-bound planets bocalled the Ekumen, lands on the planet of Geth in order to broker the planet’s inclusion in the greater galactic community. But the people of Geth are only binarily gendered for short periods during their heat (a wryly funny detail on a planet defined by its ice), and Ai must come to terms with a gender fluidity that is anything but binary, and comes back greatly changed himself.

In The Dispossessed, in which Le Guin details the invention of the ansible (and the dialectic between capitalism and communism, like you do), the story bends and circles, becoming something like a möbius or ouroboros: the end is the beginning and the beginning, the end. I read the trilogy of books that make up the Annals of Western Shore out of publication order, but it didn’t matter; each story wraps around to the other.

It seems fitting that the only novel of hers I haven’t finished is Always Coming Home, which Le Guin described as taking place in a “near-far/future-past.” It’s set in California, where she was raised, and takes place in a strange close-distance, both nostalgic and whatever the opposite of nostalgic is, at the same time. I’m glad now I have that final novel to loop back to, coming home, always and again, to Ursula K. Le Guin.

Ursula K. Le Guin, 1929-2018.