11 Authors Discuss Michael Jackson, Being Undocumented, and More in June’s YA Open Mic

YA Open Mic is a monthly series in which YA authors share personal stories on topics of their choice. The aim of the series, above all, is to peel away the formality of bios and offer authors a platform to talk about something readers won’t necessarily find on their websites.

YA Open Mic is a monthly series in which YA authors share personal stories on topics of their choice. The aim of the series, above all, is to peel away the formality of bios and offer authors a platform to talk about something readers won’t necessarily find on their websites.

This month, 11 authors discuss everything from Michael Jackson to Hurricane Katrina to being an undocumented immigrant. All have YA books that release this month.

Check out previous YA Open Mic posts here.

Sarvenaz Tash, author of The Geek’s Guide to Unrequited Love

It’s 1984 in Iran and a little girl is happily glued to the television screen. The air raid is over, the electricity has come back, and she can now indulge in her favorite pastime: watching a bootleg VHS of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” When the 14-minute video is over, and MJ turns around to reveal his yellow cat eyes, she knows she will rewind it to watch it one more time. And then again. She’ll be dressed in her favorite outfit: a red terry cloth tank top and matching shorts. Red because that’s the color Michael Jackson wears in the video.

Okay, I’ll stop talking in the third person now. But, obviously, that little girl was me. And two years later, when my parents decided to leave our war-torn country for America, it was MJ who made me feel less alone. I was a shy, sensitive kid who started kindergarten without speaking a word of English, who desperately missed her grandparents, and who wanted more than anything not to feel like such a misfit. But when I turned on the TV, there he was: my idol. It turned out that people in this strange land loved him just as much as I did.

Years later, when I was a teen, it was no longer cool to like Michael Jackson and so I hid it. I hid a lot of things about myself in those years. My love for MJ, and also for Elvis and all things ’50s and ’60s. My writing. Most of all, my writing. I wanted so badly to be an author one day, but I couldn’t imagine, for one moment, showing my work to anyone.

And then something happened my senior year of high school. Bolstered by true friends, and a realization that other people’s opinions didn’t matter quite so much, I applied to film school on a whim. And I got in. Those four years forced me to confront who I was, what I wanted to do, and—most of all—the art I wanted to make. They reminded me of how important art had been in my life, reinforcing the truth that I learned first of all from MJ: that there is beauty in things that know no nationalities, no language barriers, and no boundaries.

Sara Saedi, author of Never Ever

Does this sound familiar?

It’s the first day of school and your teacher asks each student in the class to share something personal about themselves. Something most people don’t know. So, you shift in your seat and nervously wait your turn, and then you give some cookie-cutter response like: I’m really into nail art. Or, I supported Zayn’s decision to leave One Direction to pursue his solo career.

We played this game when I was a teenager, and here’s how I always imagined answering:

“No one knows that I’m an illegal immigrant.”

I’m sure everyone, including the teacher, would have been shocked to hear this. For starters, I was only two when I moved from Iran to America. I spoke fluent English. With my light hair and light skin, some of my classmates probably didn’t even know I was foreign (though the unibrow may have been a dead giveaway). On the surface, I was a normal teenager.

Back then, there weren’t as many politicians giving stump speeches about building walls and banning immigrants. But there was still a sense that illegal immigrants were lazy. Why couldn’t they go through the proper channels before moving to this country?

Well, that’s easier said than done during a violent revolution and a war. My parents weren’t thinking…Gosh, I hope my kids don’t die in the 5+ years it could take us to get green cards. They were thinking: RUN. RUN LIKE THE WIND.

We escaped Iran and came to America with visitor’s visas, and when those expired, it took us seventeen years to become permanent residents. I will spare you the ups and downs of navigating the INS, but suffice it to say: it totally sucked. And contrary to popular belief, my parents had jobs and paid taxes.

Looking back, I wish I wasn’t so ashamed about my immigration status. Of course, I was terrified that we’d get deported, but we were good people who simply didn’t have the money and resources to become citizens. When I think of young kids like me who are coming here from Syria or Mexico or India, desperate for a better life, I don’t want to wave at them from the other side of a wall. I’d much prefer to give them a hug and tell them everything is going to be okay. And then I’d give them a copy of Zayn Malik’s solo album, so we could bond over it (trust me, it’s good).

Lois Metzger, author of Change Places with Me

This is one of the few pictures I have of me and my dad. There was a boxing event at my school, P.S. 165 in Flushing, Queens, NYC, and Rocky Graziano, one-time world middleweight champion, has his arm around me. My dad is in sunglasses.

My dad worked in Manhattan’s Garment District for most of his adult life. One day, about a year after this picture was taken, he said I should come with him to work and pick out a winter coat. He worked in ladies’ and juniors’ coats, and some were small enough to fit me.

We had to leave our apartment incredibly early, around 6 a.m., because my dad opened up the place. After a bus ride when it was still dark, we arrived at the Union Turnpike subway station and got on an F train, empty at that hour. We didn’t talk. That wasn’t unusual.

When we pulled into the 34th Street station in Manhattan, my dad just got up and off the train. For a second I sat there, not quite believing it. He hadn’t said, “Let’s go—this is our stop.” I looked at the empty seat beside me, and ran to the doors, which closed in my face, and then, a heartbeat later, opened up again. My dad was heading for the stairs.

“Dad!” I called out.

He turned around, stunned. “Oh, I’m sorry,” he said. “I forgot about you.”

“I know!”

“I mean I really forgot for a minute, like, completely.”

I felt very strange, and kind of erased. For a few seconds everything around me, the gray concrete walls of the subway station, the hollow echoing sounds, the glare of fluorescent lights, began to seem less substantial.

“I’m really sorry,” he said again. “C’mon, let’s go to the showroom and you can pick out a nice coat.”

I hadn’t heard of science fiction yet, but I think this was when my lifelong fascination with it began. Years later, when I read Philip K. Dick’s Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, it felt like a novel-length version of my experience. It’s about a glitch in reality—a famous TV personality suddenly finds that no one recognizes him or even knows who he is, and not only that, he can’t come up with any proof that he ever existed. Makes me glad I still have this picture. We’re all there—me, my dad, and Rocky Graziano.

Aditi Khorana, author of Mirror in the Sky

Every September, I watched my grandmother as she undertook her annual tradition: slice limes into quarters, hack open dozens of unripe mangoes, chop cauliflower into florets and carrots into rounds. She’d plunge caperberries into jars full of brine and oil and spices. She’d painstakingly make simple syrups blended with fistfuls of salt, bishop’s weed, and red chili.

She would work for days at a time, ladling hot and sweet and sour achaars (or pickles) into sterilized jars. She placed those jars on the back verandah under the hot New Delhi sunlight.

And then we would wait.

My grandmother had a method and it was precise. It had steps that had been perfected over generations and she knew them by heart.

But the most important step, the thing that allowed the pickles to actually become, involved waiting. Sometimes this interval between doing the work and reaping the reward was a matter of weeks, sometimes longer.

Of course there was gratification tied to the doing, but the necessary interim is where I always struggled.

“Are they ready yet?” I would ask her, my mouth watering at the thought of delicious orbs of lime suspended in a ginger syrup.

“Not yet. But they will be.”

And so we waited.

There was never a doubt in her mind that those ingredients that she had carefully combined would eventually become pickles.

My grandmother passed away over a decade ago, but every time I work on a new manuscript, I think about her. I think about her patience, her confidence in her own part of the equation of creating. I think about the simple gratification that comes from making something and then waiting for it to become.

Because that’s really what it’s all about, isn’t it? Anything good or great or fun or delicious or inspiring—whether it’s a work of art or a jar of achaar—takes work and patience. My grandmother taught me that.

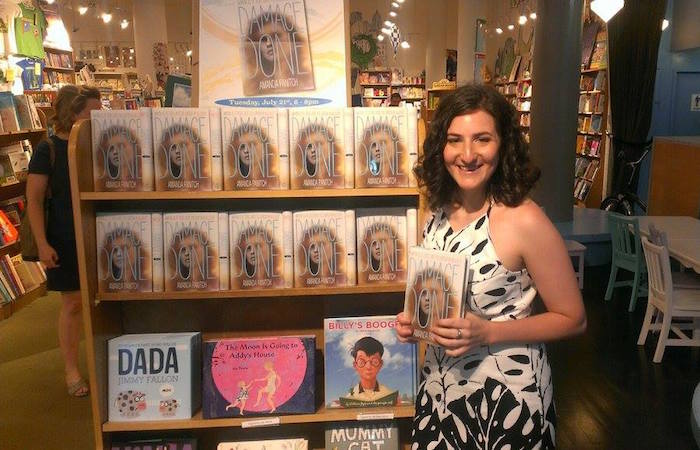

Amanda Panitch, author of Never Missing, Never Found

Teen Me was terrified of being alone. I pretended to laugh along with the girls at the lunch table as they made fun of my frizzy hair and big nose so that I wouldn’t have to sit in the corner by myself. I clung to toxic friendships even as the poison made my world blurry.

“Jen”‘s poison didn’t come with a bite. As we giggled about boys and talked on the phone, behind my back she was passing around a notebook, where she discussed how ugly I was on a scale of 1–10 and rhymed my last name with “bitch.” I confronted her when I found out, but she never apologized. We became “friends” again soon after. If I’d cut her out of my life, I might’ve lost my other friends, too, and anything was better than being alone.

Sophomore year, we took a school trip to Disney World. A group of us walked into Epcot, bubbling over with excitement, when Jen stopped short. “Amanda, you’re annoying me,” she said. “I don’t want to hang out with you anymore.” She took the others and left me sobbing in the middle of the park. I went crawling back to her later that day.

Months after, I was at one of the others’ houses when she decided to call up Jen. Something inside me finally snapped. I burst into tears and called my mom to pick me up. My friends were baffled; either they’d never noticed the things Jen did to me, or they’d chosen not to notice. Either way, they stayed with Jen when I left.

Eventually, I’d make new friends. Good friends. But Jen would stick with me: even ten years later, I can’t entirely shake the way Jen made me feel, like I’m always balancing on the edge of a cliff, the world whispering behind me.

I didn’t know either of those things then. All I knew on the drive home was that the wind was tangling in my hair, and I was alone, and I was so terribly free.

Kenneth Logan, author of True Letters from a Fictional Life

Normally on such a blue sky day, I would’ve sped out of school, turned up the radio, and unknotted my tie all at the same time. That afternoon, though, I shuffled into the throng of blue and white collared shirts. Standing on car hoods, boys glanced at their watches and chatted as if waiting for a train.

Duane paced in a clearing at the mob’s center. A skinny, whiny kid, he was usually desperate to be the class clown. Now he tried to spit but only made the sound.

The clang of the gym door kicking open turned our heads. Someone chuckled, “Uh oh.” Patrick O’Dea wore half his baseball uniform: white T-shirt, no cleats, just white socks pulled up to the knees of his blue trousers. Rumored to have a bar tab, he was the hero or villain of a dozen crude and criminal stories. He walked fast, with long strides, his head down, fists already clenched.

Duane took a cartoonish boxer’s stance—feet planted side by side, fists frozen in front of his face—and watched the bull’s approach.

Glaring up from under his baseball cap, Patrick never slowed down. He parted the crowd without breaking his stride, stepped in front of Duane, and leveled him with a single left roundhouse to the head. Then he turned and stalked back to the gym.

Kids hopped off cars, shrugging, laughing, shaking their heads. A couple of them helped Duane up, pressed a T-shirt to his face.

As I drove home, my radio low, my tie still kissing my top button, I was relieved that I wasn’t a Duane, willing to suffer abuse for attention. But I wondered what I’d be like if I had a left hook like Patrick O’Dea’s.

Donna Freitas, author of Unplugged

So, confession: I am a total social media failure.

I’m not on Facebook (though I used to be). I have Twitter, but I can’t manage to go on it like any normal person. I’ve tried other platforms. I always fail.

There’s a reason I can’t do it—and it’s really a can’t, not a won’t.

It triggers my PTSD. I was stalked for years by a person with a lot of power over me, my education, my future, and my life.

My stalker destroyed my sense of safety, my sanity, my ability to be in the world like a normal person. He was always lurking, always watching, always lying in wait. My life became about hiding from him, avoiding him, shrinking from everything and everyone. I learned to keep to myself. I was so ashamed and scared that I’d done something to make this powerful man that everyone around me loved and admired target me. That I’d asked for it somehow. It was such a lonely and isolating time.

Like a lot of survivors, I suffer from those what-if’s, from shame and self-blame.

The good news? That period of my life, and even my PTSD symptoms, feel far away today.

Except when I’m on social media.

When I used to post on Facebook, I’d spend the rest of my day sick to my stomach, everything queasy, full of anxiety and unease. Even though I knew I’d go back to my page and find it full of “likes” and nice comments, posting just wrecked me. I couldn’t understand why it made me so stressed out. It took me a lot of posting before I made the connection, and realized that posting was triggering my PTSD. It’s hard to explain, but the best I can do to describe why social media triggers me, is because posting makes me feel like I’ve given away control, that I’ve made myself vulnerable. Because when I post I am asking for attention. I am putting myself out there where anyone, absolutely anyone can get to me. Posting, unfortunately, takes me back to that terrible place I lived for so long.

Then why am I doing this blog post?

Because I’m good at responding when people ask me to contribute to their pages and sites—there’s something about someone else generating the need for me to put myself out there that makes me feel more protected. It means I’m not alone when I put something out there. I appreciate it when someone extends the invitation—it empowers me to go to a place that is too stressful to go to on my own.

Writing Unplugged was good for me. It allowed me to play around with ideas about the virtual and with the ways people connect (and don’t) today, both the good and the fun and even the fearful, but in a way that made me feel safe. I am grateful that writing books gives me a space to engage the things that are difficult in my real life.

Pintip Dunn, author of The Darkest Lie

My junior year of college, my hands froze. As in, the muscles from my neck to my shoulders to my elbows locked up. And they stayed that way for a week. I couldn’t brush my hair. I couldn’t bring a fork to my mouth. All I could do was lie in bed, terrified my life was never going to be the same.

It wasn’t. And a part of me couldn’t be more grateful.

Oh, I’m not grateful for the physical pain. I wouldn’t wish that on anybody. I was eventually diagnosed with fibromyalgia/RSI. I got through college and law school by hiring a typist and taking my exams—even the bar exam—orally. To this day, I can’t type on a keyboard without my neck and shoulders screaming.

This disability, however, led me to my true calling. There was enormous pressure on me to have a secure and lucrative career, and I became a litigation attorney at a corporate law firm. Then, I had a flareup that landed me flat on my back for six months. In the midst of this suffering, I had an epiphany. My body wasn’t punishing me. It was talking to me, in a way I couldn’t ignore. It was telling me: Get off this path. This isn’t what you’re supposed to be doing.

I’ve wanted to be an author since I was six years old—but I put that frivolous dream aside. I think the voice inside me was sick of being ignored. It had to speak louder and louder, in the only way it knew how, until I finally listened. Until I finally understood I had no choice but to follow my dream.

I left the legal profession and never looked back.

I still can’t type. But I can tap on my cell phone if it’s locked in portrait position. I’ve written my last six books this way, and I hope to write many more.

Jenn P. Nguyen, author of The Way to Game the Walk of Shame

Living in New Orleans my entire life, I wasn’t a stranger to hurricanes. Then, in my first week as a college freshman, a little storm called Hurricane Katrina happened. My family usually stayed and waited the storm out. But this time my dad told us to pack up and evacuate. That should have been my first clue that this wasn’t an ordinary storm. Over the next couple of days, my family and I were glued to the TV and watched as neighborhoods flooded. The levee broke. People were rescued from their rooftops in boats and helicopters. And the whole time, it still never hit me what this actually meant. It was like I was watching a movie. Sure, it was horrible and tragic, but it didn’t personally affect me. Except that it did.

My house ended up being flooded to the second floor.

For the next several months, my family and I jumped among relatives and friends’ homes, apartments, etc. We moved over ten times within seven months. Everything I owned basically fit in a medium-sized box—including my Harry Potter hardcover collection.

Yet as we moved from place to place, I found fanfiction and roleplaying sites that paved the way for me to write. I always wanted to be a writer, but was too much of a realist to believe I would ever get published. But with all the moving and uncertainty of the future, writing brought a sense of escape for me. And now I was days away from being published.

Sometimes good things can come when you least expect it. Even if it is ten years in the making.

Cynthia Hand, coauthor of My Lady Jane

When I was 21, my boyfriend let his dad read one of my short stories. I had just decided to make writing my career, you see, so my boyfriend wanted to see if I was “talented.” His dad was a university professor, an expert on good writing, so my boyfriend thought he’d be a good judge of whether I should really be a writer.

When he told me he sent his dad the story, I was shocked. The story in question had been one I’d written just weeks after a death in my family, and it was more nonfiction than fiction. I had poured my raw, hurting heart into that story.

“Well, what did he think?” I asked nervously.

My boyfriend was quiet for a minute. “He said it was typical. The story was just an average story about an average girl. He didn’t think there was anything special about it.”

My boyfriend didn’t stay my boyfriend for long after that. But I think about that moment a lot, when I found out that a stranger I’d never met read my most vulnerable piece of writing and decided that it wasn’t much good.

And I think about how I decided to be a writer anyway. To keep pouring my heart out, anyway. To keep writing.

Because, in the end, you have to write for yourself and no one else.

Lindsay Ribar, author of Rocks Fall Everyone Dies

The tattoo on my arm says Mischief Managed. I got it because I’m a Harry Potter fan. Duh, right? Right. Except that’s not the only reason I got it.

A few weeks ago, I was at a bar with a handful of other authors. All friends, all totally awesome people. We were talking about the publishing industry, as tends to happen, and for no real reason it suddenly occurred to me that I was the only person there who’d never been on a bestseller list. Not only that, I was the only one there who’d never been a full-time writer. I am not successful enough, I thought. I am not a real writer. I do not belong at this table.

It was far from the first time I’d stumbled into that thought process. Sometimes I’m not a real writer because I don’t have an MFA. Other times it’s because I don’t write every day. Or because I love fanfiction just as much as published books. I’m not a real writer because I don’t outline, because I never get the story right on the first try, because I don’t think of my characters as real people, because I don’t produce at least one book a year, because I haven’t won awards, because blah blah blah.

Imposter Syndrome is a lying liar, is what I’m trying to say. Because, the truth is, full-time writers aren’t judging me for having a day job. Plotters aren’t judging me for being a pantser. Folks with creative writing MFAs aren’t judging me for not having one. That’s all me, comparing myself to strangers (and sometimes friends! gah!) and, for no reason at all, finding myself wanting.

It’s not healthy. It’s not fun. And it’s something I constantly struggle with. But here’s something else that happened:

Once upon a time, when I the only writing I did was Harry Potter fanfiction, I had the idea of writing an original book and getting it published. The idea became a goal; the goal became something I managed (many years later) to achieve. And I didn’t do that by comparing myself to other people. I did it by figuring out my own way. The tattoo I got was a commemoration of that. A goal, achieved. A bit of mischief, managed.

A reminder that I do my best work when I’m not letting I don’t belong here get in the way.