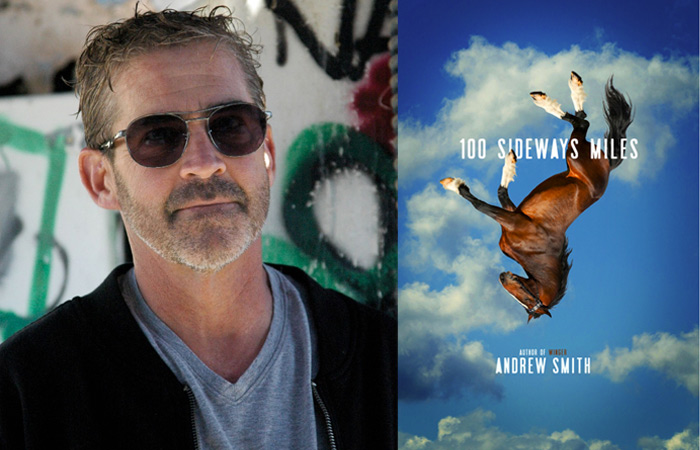

An Interview With YA Author Andrew Smith

Andrew Smith writes some of the richest, realest fiction on the YA shelves, even when he’s writing about nightmarish alternate worlds and grasshopper plagues. In February’s genre-bending Grasshopper Jungle, a delicate love triangle between a sexually confused boy and his girlfriend and male best friend plays out against the backdrop of a terrifying man-eating bug apocalypse. This month’s 100 Sideways Miles follows equally confused Finn Easton, whose life thus far has been defined by the freak childhood accident that killed his mother and gave him epilepsy, and by The Lazarus Door, a controversial novel written by his famous father and featuring a character who shares Finn’s name. Our Finn spends his junior year trying to “get out of the book,” with help from his legendary best friend, Cade Hernandez, and his first love, a complicated girl named Julia. I spoke to Smith about his themes, his writing schedule, and the ways art comes from life:

Your stories have so many threads beyond straight plot. Do you tend to start with character, plot arc, or with the curious ideas that preoccupy your central characters?

I actually do start my stories with a particular quirky idea (like a dead horse falling out of the sky, or how two teens might trigger the end of the world in a recession-wracked Midwestern town) and then build a small universe around that idea.

I love your books in part because they feel rawer, weirder, and more “anything can happen” than a lot of what’s currently on the shelves. Have you learned as a reader how to have that kind of narrative freedom, or is it just the way your books come together?

I am easily distracted and easily bored. I can’t endure sitting through things that I’ve seen done before, so there is a conscious effort on my part to try to do something that I’ve never tried and tell a story that I’ve never heard. You have to get into kind of weird territory when you put those constraints on your performance.

Did you write or plot more of Finn’s father’s book, The Lazarus Door, than was used?

As a matter of fact, I did write more of that novel-in-a-novel before I decided to use it in 100 Sideways Miles. The opening quote I use in the novel was actually the beginning of that other book. Also, I wrote a short story called The Planet of Humans and Dogs for an anthology that was eventually scrubbed, that was part of what would have been The Lazarus Door.

Sexuality is very fluid in your books, in a way that’s really exciting to see in YA. Why do you think it’s important for teens to see that in books? What are other books you love that showcase the diversity of sexuality?

To address the first part of the question: I’m not prescriptive with what I do. I offer no lessons for readers on what they “should” be exposed to, or how they should handle it. On the other hand, I will say that I get so many letters from readers (young and old) that echo the same message to me–thank you for writing this because it makes me feel like I’m not the only one out here. For the second part of the question, I can list a few: Ask the Passengers, by A.S. King; Two Boys Kissing, by David Levithan; Noggin, by John Corey Whaley; and Will Grayson, Will Grayson, by John Green and David Levithan.

Your character’s voices are incredible, and they think so much about everything. Do you find yourself particularly drawn to people/characters who live highly examined lives?

I remember when my first novel, Ghost Medicine, was published, and I got a fairly nasty email from a reader who told me something along the lines of “boys are never THAT introspective.” Speaking as a male, I have always had a very noisy, self-doubting, introspective head. I can’t help but write about characters who have the same thing going on.

Have you ever used elements of people in your own life in your books, Finn-in-Lazarus Door-style? If so, did their objections (or imagined objections) inspire Finn’s?

Well, I think all writers use real elements—people, experiences, and place—to inform their fiction, and I have never encountered any objections. I know guys who played rugby who could see themselves in characters and situations I wrote about in Winger, but I’d never confess the truth behind any of that stuff. As far as Finn and his father in 100 Sideways Miles, though, I wrote the book during the time when I was first taking my son away to college, and I did originally intend the book to be about only Finn and his dad—and what might happen if they never got to the college Finn was supposed to go to. Then I started to wonder what if my son felt like I was scripting his life too closely? And that became one of the important ideas in the book, not just from a writer-son perspective, but a universal father-son thing. When my son did read the novel (I only let family members read my stuff after it’s published in ARC form), he told me two things: first, that it was his favorite Andrew Smith book; and, second, that he felt like every page in the book was actually about him. We have a tremendously close relationship, by the way.

Perhaps the most dramatic scene in 100 Sideways Miles feels deliberately underplayed, whereas smaller moments are made to feel big. Why did you make that choice?

I don’t know if it’s truly a choice. I think one of the things that is a characteristic of my style is the degree to which I tend to focus in on the small. I often have characters who wander through their stories overwhelmed by the largeness of everything going on around them. It’s kind of the way I feel most of the time. Also, the thing about the (climactic scene) in 100 Sideways Miles that was important to me is the idea of choice. This is a big issue for Finn throughout the novel—does he actually have a choice in what he does and what happens to him? Cade certainly always seems to be in charge of his actions, but that scene is where, I think, Finn finally realizes he does have free will and is capable of making choices that may steer him away from what he thought was a carefully controlled script.

You’re very prolific. What does your writing routine look like?

It’s a mess. I can’t get anything done and I have to so strictly plot out minutes and hours of every day to the point that if there’s the slightest hitch in my plans, I go nuts. Which kind of reminds me of Finn. I do not watch television at all. No offense to TV watchers—I just don’t have TV in my schedule. I get up before 3 a.m. every day to start writing. I don’t set word count goals for myself because to me there’s a natural flaw in that. Anyone can write 3,000 words of pure horseshit in a day.

You’ve said that you don’t pre-plot, instead just letting the stories come. How much do your first drafts tend to resemble your final books?

Well, my first version (I never consider what I do as “drafting.” Sorry if that sounds douchey) of 100 Sideways Miles was completely insane and I knew it. But I was going through a very sad time due to my son moving away, so I just let those pages have all the insanity I could purge from my head. I realized the novel was over-the-top crazy, so I rewrote the entire thing. There was almost no editing on it at all. There were also almost no differences between my first version and the published version of Grasshopper Jungle, too.

After six books, why do you think it was Winger that became your breakout novel?

Winger, like 100 Sideways Miles, was published by Simon & Schuster. They did things for me that nobody ever did before, like take out ADVERTISEMENTS. Sorry if that sounds harsh, but it’s true. Their school and library/retail/marketing outreach is phenomenal. So is Penguin’s (my publisher for Grasshopper Jungle and The Alex Crow, which is coming in March). It was funny and at the same time sad for me when, after Winger came out, I got so many email messages asking if I had ever written anything else. Ouch.

What books most formed your thinking or reflected who you were as a child and teen reader?

When I was a teen, my favorite things were Stephen King, unattainable girls, and the thickest, cheapest, classics paperbacks I could get my hands on (like Thomas Hardy or Fyodor Dostoevsky). I was pretty lonely and pathetic.

What are some the best responses you’ve gotten from young readers to your work?

The best responses from young readers, I think, are too personal for me to describe in detail publicly. I’ll tell you the subject line of an email I got from a teen girl, though. It went like this: YOUR BOOK WINGER CHANGED MY LIFE. I still exchange emails with that girl, too.

Is there a possibility of a Grasshopper Jungle sequel?

The first few times people asked me this question, I responded with an immediate NO. I realize that I can’t entirely rule it out, though. It could be fun.

Beyond Grasshopper Jungle and 100 Sideways Miles, what 2014 releases are you most excited about?

2014 books I love: Glory O’Brien’s History of the Future, by A.S. King; Noggin, by John Corey Whaley; The Impossible Knife of Memory, by Laurie Halse Anderson; The Wrenchies, a graphic novel by Farel Dalrymple; The Scar Boys, by Len Vlahos; Guy In Real Life, by Steve Brezenoff; and We Were Liars, by E. Lockhart. Lots of GREAT books came out this year, which kind of sucks because I only wanted TWO great books to come out in 2014.

100 Sideways Miles is in stores now!